Blessed be Tashkent, a city that is called a breadbasket even in times of civil unrest! Yet one’s daily bread has to be earned. Perhaps for this reason, the 15-year-old schoolboy Tolia Pozmogov, who had taken some lessons from his father, the wonderful clockmaker and brilliant mechanic Ivan Pozmogov, became responsible, from 1936 onwards, for the accuracy and trouble-free operations of clocks all over this pearl of Central Asia. These duties must have fitted in with the nature of the teenager who liked all kinds of machinery and motors, and for whom no repair-job was too daunting. It is no mere chance that he was the first on Mirabad St. to ride a motorcycle. Although various specialties attracted Anatoly, he chose a medical institute in 1939, though he didn’t drop his job as the guardian of time.

As WWII drew on, his clock began to tick differently. In July 1943 he graduated from the Tashkent Medical Institute’s Therapeutic Faculty. The family archives still contain a draft board summons: “Report obligatorily at four a.m., July 24, 1943, to the military marshaling point at 4, Paganini St., Tashkent.” Pozmogov was immediately sent to the front line. As a senior doctor (aged 22) of the 689th Antitank Artillery Regiment of the 5th Guards Armored Army, he did his service on the Steppe, Voronezh, 2nd Ukrainian, 2nd and 3rd Belarusian, and Baltic fronts. Some miracle kept him alive so that he could save others. In 1945, after a grave illness, Pozmogov was demobilized as a Patriotic War disabled veteran.

Throughout the war years he would send his sweetheart and future wife Zitsa (Zinaida Smolenska – they were happily married in September 1945) touching letters which always reached the addressee. These letters, as well as her messages, had passed military censorship and were kept for years at home, in a field bag.

And then there is the hall of the National Medical Research Library on Tolstoy St. in Kyiv, at a primitive Tereshchenko-built structure which housed the X-ray institute in the postwar years and where Pozmogov launched his academic career. A documentary film, The Deeds and Days of a Scientist, directed by Tamara Boiko is being shown there. There one can also find his daughter Zoia Chegusova-Pozmogova, National Taras Shevchenko Prize winner, Meritorious Figure of Arts of Ukraine, and a well-known art expert, who reads stunning evidence of those times, as if resurrecting the encouraging words of an unforgettable wartime song: “And so I know that nothing will happen to me…” There, against the backdrop of the tapestries “My Flowers to the Doctor and the Human” by Liudmyla Zhohol, People’s Painter of Ukraine, full member of the Architecture Academy, a commemorative soiree to mark the 90th anniversary of the birth of this uncommon and somewhat mysterious personality was held.

But why did Pozmogov choose, after so many losses and privations, radiology, an option that in fact dooms the doctor to solitude and endangers his health? Perhaps it was because this specialty is in close contact with physics and engineering, especially when it comes to inventing things, and perhaps for the simple reason that, after so many roaring years, Pozmogov, a person of calm reason, sought silence.

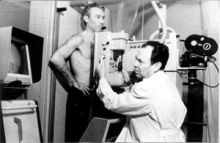

It will be recalled further on that Pozmogov worked here, at the Research Institute of Radiology and Oncology, in 1947-63, first as a junior and then as a senior research associate and a department head. The titles of his Ph.D. and higher doctorate dissertations are telling: “Tomofluorography in the X-Ray Diagnostics of Tubercular Caverns” (1952) and “The Diagnostic Value of Tomography in the Cancerous Lesion of Larynx” (1962). In essence, Pozmogov, together with Maximilian Ovoshchnikov, was a true clairvoyant in this field of medicine, and it is only his exceptional modesty that prevented him from being put on the list of prospective Stalin Prize winners. This is, of course, a hypothetical judgment, but the facts are real. Having retired as institute director shortly after he turned 65 and remaining a longtime leading consultant in radiology, Pozmogov soon forsook his salary in favor of the young specialists, contenting himself with the restored pension of a Patriotic War disabled veteran and the state scholarship for prominent academics. But it is he who organized, in those days of disastrous radiation, Ukraine’s first acute radiation sickness clinic at his highly-specialized institute. Crouched over these lines, I recall for some reason my Pravda Ukrainy article “How Chornobyl Heroes Were Healed,” printed in 1986. It was about professors Anatoly Pozmogov and Leonid Kindzelsky, both true devotees of science.

At the proposal of Vasyl Bratus, a battlefield surgeon, the rector of a Kyiv-based medical institute, and recently a minister, Pozmogov, then 42, began a three-year stint as pro-rector for research at the oldest institute, which had gathered legendary luminaries of knowledge. At the same time, he established an entirely new school of research in his capacity as head of the Radiology Department. And now a new significant turning point: in 1966-71 Pozmogov becomes deputy director of the Institute of Experimental and Clinical Oncology founded by the scholar Rostyslav Kavetsky — it was the dawn of new battles against this terrible disease. What brought the two great minds together and why was their alliance historically important? As the anti-cancer strategy was assuming new qualities and gaining further impetus in those years, Kavetsky and Pozmogov worked as an effective tandem — perhaps because they had been born to families of intellectuals, book lovers, and hermits in everyday life. Kavetsky was the son of a doctor, later rector of a medical institute in Samara and one of the closest associates of Prof. Oleksandr Bohomolets, while Pozmogov was the grandson of a Kronstadt naval officer Kuzma Panchin, of noble origin, who died in the World War I.

In 1971 Pozmogov was appointed director of what is now the National Institute of Cancer that was being built close by. He headed it for about 17 years. In all probability, if you come to think of it, he was indeed a Ukrainian Lomonosov on a street named, for no apparent reason, after the old-time Russian genius. For the institute in its present shape is Pozmogov’s brainchild: he organized 10 clinics and 4 research centers within its walls. It is a multifaceted and troublesome job to be the director of such a high-profile institution and, in addition, the chief radiologist of Ukraine’s Ministry of Public Health. But, as if defying everything, Pozmogov did not allow himself to do what any other director or administrator would have done in his place. “I had a small birthmark on the left cheek, which seemed to make me more attractive,” Liudmyla Zhohol reminisces, “but, as years went by, it began to grow. I had been his longtime patient in very difficult situations, and when we met once, he suddenly said: ‘I don’t like this French bean. Come to the institute.’ I came, and he walked me a block away to the institute’s out-patient department, where Volodymyr Hordiienko, a laser surgeon, now Meritorious Medic of Ukraine, examined me. He did not phone or summon him… He said on the way: ‘Do what he will advise you.’ Hordiienko cast a glance at the neoplasm and concluded: ‘Why should you keep it?’ He excised it very fast.

Circumstances, even sad ones, can sometimes lift a veil of mystery over life and destiny. Pozmogov was taken seriously ill in 2004, on his home stretch. Well aware of his condition, he still preferred to stay at a common hospital rather than at the elite Feofania clinic. “I was to fill out a research questionnaire,” Zoia Chegusova-Pozmogova recalls, “so I came to see father at the reanimation ward. I was let in because my husband Volodymyr Chegusov was then the chief doctor at the Solomianka hospital. We talked for a very long time, and my eyes were opened to some facts. It turned out that in 1981, after father had delivered a speech at a scholarly conference in West Germany, he received an invitation from his German colleagues to head a research institute of radiology over there. He refused out of patriotic reasons… But why did the choice fall on no other than him? At the same time I happened to see for the first time a detailed comment of the Moscow-based Prof. Pavlov, member of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, on the scholarly publications of the Meritorious Scientist of the Ukrainian SSR Anatoly Pozmogov. Although it is a purely scientific document, it still paints the picture of my father in what he devoted his life to. You can’t possibly belittle or exaggerate things here… Prof. Pavlov wrote: ‘A. I. Pozmogov is one of the first in this country and abroad to have given an unbiased assessment of tomofluography and transverse tomography. His publications comprise such new (at the time) areas as television in radiology (1966, 1969), lymphography (1970), the use of the logetron (1967) and video-magnetic recording (1970) in diagnostic radiology, powder bronchography (1959), and assessing the breathing function of lungs by way of X-ray photometry (1962). Eighteen publications are on angiography, angiopulmonography, mediastinal phlebography, and bronchial arteriography. A certificate of authorship was issued for a technique that allows to simultaneously receive the image of all large mediastinal veins, which reduces the X- ray load and the likelihood of an injury during the study. Works on this problem have been published in West Germany (1974) and the US (1975). The 15th International Congress of Radiologists, held in 1981 in Brussels, heard only one report by a Soviet delegate – that of Prof. A. I. Pozmogov, on integrating the radiological and mathematical methods of study in the diagnostics of pulmonary and mediastinal tumors.’”

This may have been research in a rough field, but it was truly modern-day medicine. Tellingly, Prof. Yakiv Babiy, one of the famous school’s disciples, presented the Pozmogov family in the first issue of a new national scholarly journal, Rentgenologia-praktyka, dedicated to Anatoly Pozmogov.

It seems that the load of things to be done, the continuous exposure to radiation, and inherent intuition outlined a relentless picture of the future to Pozmogov. “When he turned 80,” says, deep in thought, his elder daughter, a homeopathic doctor, Candidate of Sciences (Medicine), Iryna Pozmogova, “he looked very good. I was so pleased to hear a lot of good words and see gifts and smiles at a conference held in Alushta in his honor. It was all the more pleasant because father had resigned as institute director long ago. It seemed to me that we would surely celebrate his 90th birthday a decade later. But I was wrong. He had a presentiment about his death. In 2002, on The Day when a Congress of Radiologists opened in Kyiv, father said to me: ‘This is my last congress. I won’t live to see the next one.’ And, unfortunately, he was right. The 2006 congress went off without him.”

Anatoly Pozmogov used to recall the following lines:

“Brother, hold on, tooth and nail,

To all that you breathe and live with.

When you die, you’ll see

What life really is!”

What is life? The 20th-century saga of Anatoly Pozmogov tells a story of heroism, albeit without lofty words. Thanks to the love and efforts of his wonderful daughters and the entire enlightened family of this knight without a nimbus, the sun of memory seems to have risen above the field of the miraculous and noble life of a boy from Tashkent, who personified Ukraine in his next peaceful exploits. The doctor was awarded only four orders: two of the Red Star, one of the Patriotic War, 2nd degree (for his wartime merits), and one of the Red Labor Banner. But he was the foremost builder of a hearth of hope, a trailblazer in never-obsolescent methods, the savior of thousands of his wartime comrades-in-arms and later of his compatriots.