Several days ago a presentation of Timothy Snyder’s new book BLOODLANDS: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin took place at the Harvard University (Cambridge, the US) bookstore. The author is a professor at Yale University, one of the leading American researchers of Central-Eastern European history, and an expert in Polish and Ukrainian history. He authors several monographs dedicated to the history of this region, including one about the famous representative of the Austro-Hungarian imperial house, Wilhelm Habsburg, also known in Ukraine’s as Vasyl Vyshyvany.

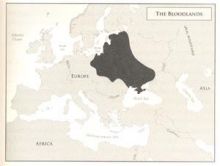

Snyder’s new book takes a comprehensive view of the totalitarian era, which the author was able to see and present from an unconventional perspective. The “Bloodlands” marked by Snyder on the map of Europe cover a considerable part of Central-Eastern Europe, stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea and situated between today’s Germany and Russia, Berlin and Moscow. They comprise Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Poland, Ukraine, and, partly, the adjacent regions.

The “Bloodlands” are not just an image, but rather a logical construction perceived by the author, and based on an obvious fact. These are the lands where, during 1933-45, the political regimes led by Stalin and Hitler committed the most atrocious crimes of the 20th century, first of all, the Holodomor and Holocaust. They are the scene of the bloodiest battles of the World War II, which took the lives of millions of soldiers, while millions of civilians met the same fate in the rears or on occupied territories.

Today, every historian and every educated reader anywhere in the world knows about these events, but Snyder overlapped the maps for each of these disasters and asked if there was a regularity in their occurring on the same territory.

Snyder notes that a profound knowledge of the history of Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, the Jewish nation — each of them separately — does not allow one to comprehend the reasons for the massacres of the population during this short historical period. The study of each national history in isolation does not show the entire phenomenon, and only their examination together with the history of Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes helps understand the reasons.

The author emphasizes that in this research the Stalinist and the Nazi regimes are examined together because it serves the cause of uniting the national histories into a whole, and the history of the “Bloodlands,” with that of Europe.

While comparing Hitler and Stalin, Snyder notes the similarity of the political regimes they both created. Both political systems grew out of the World War I, both were the result of the collapse of the Russian and German empires and of the social disasters of the early 20th century. Stalinist socialism and national-socialism are similar in their treatment of democratic institutions, territorial questions and farmers’ issues.

Even chronologically, their development was identical, 1933 being a crucial point for both. The author makes a particular emphasis on the fact that Stalin and Hitler both had similar utopian plans considering Ukraine. Both dictators needed it to develop their socialist states. Stalin was creating the Soviet model by subjecting Ukraine to the Holodomor, while Hitler, having invaded Ukraine, imposed his occupation regime. The famine in Ukraine turned out to be the deadliest man-made famine in human history, while during Hitler and Stalin’s reign in Ukraine, more people died there than in all the other “Bloodlands,” and more than in the rest of Europe.

In the author’s opinion, the epoch of mass murders in Europe began in 1933. A little Ukrainian boy who starved to death early in 1933; a young man executed, after his wife, in 1937; a Polish officer, killed in 1940; a little Russian girl who died from hunger in besieged Leningrad at the end of 1941; and a little Jewish girl who wrote a good-bye letter to her father in the summer of 1942, before she was killed — they all turn out to be victims of the most horrible bloody bacchanalia in human history, made by two totalitarian political regimes.

Snyder singles out three stages of the “epoch of mass killing” in the “Bloodlands.” The first was in 1933-39, when the major crimes against humanity were committed at Stalin’s orders. The second, in 1939-41, was the period when the crimes committed by both regimes were comparable in size; and the third was in 1941-44, when Hitler was in the lead. “In the middle of Europe, in the middle of the 20th century, the Nazist and Soviet regimes killed nearly 14 million people.” The author does not include here the soldiers fallen in the World War II, as he did not include military operations in his research; but he notes that these lands account for at least a half of all immediate casualties in the greatest war in human history.

Seen from a factual perspective, the book is a sad martyrology of the Stalinist and Nazi regimes, which hardly differed on the most basic philosophical issue — the treatment of human life. In some chapters, the author adduces a survey of the Holodomor tragedies, class terror, national terror, murders and deportations over a brief period of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the “ultimate solution” to the Jewish question by means of shootings and the Nazi factories of death, ethnic purges (deportations of millions of people after the war), etc.

The very title of Snyder’s book immediately suggests that it must be largely concerned with the history of Ukraine, since all of the mentioned disasters were taking place first of all on its territory. Snyder is also well aware of it. At the very start of his foreword, he emphasized the Ukrainian dimension of totalitarianism.

The authorial analysis of the history of the Holodomor in Ukraine proves that this tragedy is commonly acknowledged and known to be one of the most dreadful disasters in world history. By the way, a week before the Snyder presentation, the same bookstore held another one, Frank Dikotter’s research on the man-made famine of 1958-62 in China. Dikotter has several times compared the man-made famine masterminded by Mao Zedong and the Stalinist Holodomor in Ukraine.

Snyder’s work is also shows that Western scholars dispose of a considerable pool of primary sources about the Great Famine in Ukraine and have their own opinions about it. The author accentuates Stalin’s personal participation in masterminding the Holodomor at each stage, mentions the Western witnesses of the Ukrainian genocide, makes an attempt to estimate the overall victims, gives a legal assessment of this crime against humanity, and evaluates its significance and consequences.

The scholar notes that in the spring of 1933, more than 10,000 people were dying in Ukraine each day. As far as overall loss of life goes, he believes the figure of 3.3 million to be the most likely. Rafal Lemkin, an international lawyer, called the famine in Ukraine “a classic example of Soviet genocide.” Evidently, by adducing this quote, the author indicates that he agrees with it. One can also share the author’s idea of the psychological and political consequences of the Holodomor: out of the surviving peasants, hundreds of thousands became Soviet citizens, but no longer Ukrainians.

At the same time Snyder does not overlook another, no less complicated issue: the treatment of the Holodomor by contemporary Western democracies. Western countries would turn a deaf ear to the appeals from Ukrainians in Poland to render any possible aid to Ukraine. The West would rather trust Soviet counterpropaganda than the horrendous facts which seemed just improbable to the Western politicians.

It is curious that in August 1933, the regime put up a show for the ex-prime-minister of France in Kyiv: the city was closed for any outside visitors, the residents were told to wear their best clothes, motor cars were brought in from the nearby towns and cities, and the stores were packed full with food. The French politician was taken on a drive down Khreshchatyk, treated to all sorts of delicacies, and he believed everything he had been told by the Soviet officials. As a result of such operations, the West turned a blind eye to the Holodomor, and it was in that very year that Roosevelt established diplomatic relations between the US and the USSR.

Only a few Western journalists were able to break through the “wall of silence,” learn about the real situation, and had enough courage to make it public. One of them. Gareth Jones, in March 1933 boarded a train in Kharkiv, got off at a small station, and saw the horrible scene of people dying together. He handed out the food he had with himself to the starving people. A little girl told him, “Now that I have eaten such dainties I’ll die happy.”

Ukrainians also suffered the most in the reprisals of 1937-38 (against the so-called kulaks and nationalists). Vinnytsia was one of the most terrible sites of mass murder. Eighty-seven mass graves have been found around the city.

Stalin was a pioneer of national terror, while Hitler took over and improved his practices. Back in those years, Hitler’s mass murder machine was gaining momentum. It would soon work at full capacity.

The author does not overlook the problem of the national composition of the NKVD during the mass reprisals — he noted a rather significant fact that at the onset of the terror of 1937-38 one-third of top NKVD officers were Jewish, but by the end of 1939, only four percent had remained. The death machine was ruthlessly killing its executors — yet not blindly, it followed a certain logic inspired from above. The author dubs the terror of 1937-38 the “third Russian revolution,” but in fact it was a Stalinist counter-revolution.

While Ukrainians, and later “the enemies of the people” became the first victims of the Stalinist regime, Poles turned out to be the fist victims of the Nazis. With the start of WWII both Hitler and Stalin tried their best to solve the Polish question to their advantage. The Katyn tragedy (now double-tragedy) was one of the vivid examples of the Soviet regime’s treatment of potential opponents. 20 thousand Polish officers, most of them reservists belonging to the Polish political, intellectual, and professional elite, died. They were being executed in three places, Katyn, Kalinin, and Kharkiv. In Kalinin, several thousand people were killed by one butcher, the chief of the local NKVD, who killed 250 persons each night. Stalin and Hitler together killed over 200 thousand Poles, and Stalin sent another two million to the GULAG.

The Polish tragedy was closely connected to both the Ukrainian lands and the fates of Ukrainians themselves — for besides ethnic purges of Western Ukrainians by Poles, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians became victims to Stalinist reprisal machine. They were either physically exterminated or deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan as bourgeois nationalists or traitors.

The scholar also touches upon the Ukrainian-Polish conflict in passing, but he does not dwell on its reasons and history. Addressing the problem of national terror in the times of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, he mostly considers the Polish tragedy, and the Jewish Holocaust as next in chronology.

The author explains Hitler’s assault upon the USSR first and foremost by his desire to occupy Ukraine. According to his data, 90 percent of the Soviet foodstuffs were produced in Ukraine at that time. By using famine and collectivization, Stalin forced Ukrainians to work for his system. Hitler wanted to do the same for his. The Nazi top leadership was convinced that the occupation of Ukraine would solve most of Germany’s economic problems. German analysts maintained that Ukraine was the most important part of the USSR, and the Generalplan Ost was largely designed to exploit Ukraine’s resources. For this, Germans intended to preserve kolkhozes as the most convenient means to achieve their ends. For Stalin, Ukraine was supposed to be his fortress, while for Hitler, his breadbasket. The author is convinced that the seizure of Ukraine would have enabled Germany to become a super power.

The beginning of the war resulted not only in disastrous casualties, but also in a massive loss of life among the civilians, and deaths of hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war in German concentration camps. Hitler’s invasion in the USSR provoked him to finally solve the Jewish question as well. Before 1939, Jews were allowed to leave Germany, a part of them had been deported to Poland, and there even existed a quasi-plan to deport Jews to Madagascar, then France’s colony. The latter being defeated, Hitler could dream of its overseas colonies, but the ocean was still controlled by Britain. Therefore the Madagascar Plan had to be given up and substituted with something else. The substitution was eventually found, in the shape of their mass elimination.

The onset of the Holocaust coincided with the first days of the war. Germans killed Jews on the newly occupied territories, shifting the blame for the NKVD crimes on them. In Lutsk, where more than 2,000 inmates were shot in the NKVD execution cellars, Nazis killed 2,000 Jews and declared that to be revenge for the murdered Ukrainians. Then the death factories opened: Hitler and Himmler embarked upon “the ultimate solution” of the Jewish question.

The World War II had a special impact on the fates of the Belarusian people. It was in those particular years that Belarusians suffered the most of all the people inhabiting the “Bloodlands.” They, too, fell victim to the joint terror by the Stalinist and Nazi regimes. The author is convinced that the Soviet guerrillas, who from 1942 on had been under Moscow’s growing control, provoked with their actions mass killings of civilians in Belarusian villages. Other examples of similar massacres were the two Warsaw uprisings, in 1943 and 1944.

The last large-scale tragedy in the “Bloodlands” (carried out with partial consent of the Western allies) were the ethnic purges of the first post-war years. Deportations of tens of millions of people from one country to another were unprecedented not only in European, but also in world history. A mass deportation of Germans was supposed to be not only a revenge for the war, but also to reconcile Poland with the Soviet regime, and arouse sympathy for Communists.

Stalin allowed to expand the Polish territory far out west and turn it from a multinational country into an “ethnically pure” national one. All in all, by the end of 1947, 7.6 million Germans had been deported to the West, and another 400 thousand died during those forced deportations. The author remarks that it was an ethnic purge, but the result was totally opposite to what Hitler had planned in his time: instead of inhabiting new lands, Germans were driven into the limits which were defined for them.

Ethnic and political purges and deportations also spread to Western Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic. Nearly two million Poles were deported from these regions to Poland. On the other hand, from beyond the new Poland-Ukraine border, almost half a million Ukrainians were deported to Ukraine. A massive stream of Ukrainian victims flowed east to the GULAG, and in Poland, in the course of Operation Vistula, it also flowed to the west of the country. Similar actions were held by the Soviet regime against Lithuanians, Letts, Estonians. Several nations, such as Chechens, Ingushes, and Tatars, were completely resettled.

Throughout all of his research, Snyder does not make a point of focusing on Ukraine. He rather is interested in Poland and the Poles. He sometimes regards the events in Western Ukraine in the light of “different” historiographies, being not familiar enough with all of the Ukrainian historical literature. Unwilling to lose track of the main subject, the author consciously leaves “the GULAG archipelago” out of the limelight, as well as Romania and other countries where crimes against humanity were also committed. As a matter of fact, the GULAG victims where primarily the residents of the “Bloodlands.”

The scholar concludes his research with a totalling of the victims to both the dictators. In Ukraine, the Stalinist regime, with its Holodomor and reprisals, took 3.5 million souls. The same number actually was the toll taken by the Nazi regime (the Holocaust and mass killings of civilians). All in all, seven million Ukrainians, Jews, Poles, and other nations fell victims of a conscious and deliberate mass extermination of people. Besides, another three million of soldiers and civilians died in and out of hostilities. Thus the toll of the harvest of sorrow on the territory of Ukraine reaches 10 million lives. Comparing Ukraine with the other “Bloodlands,” the author arrives at the conclusion that it was in the focus of Stalinist and Nazi policies of mass extermination of population during the entire epoch of mass killings.

It seems as if Stalin and Hitler had been engaged in a sort of competition in slaughter in the “Bloodlands.” Snyder was not the first to compare the two dictators. He did not forget his predecessors, who found the common denominator for both regimes — totalitarianism, which in practice took the shape of brutal neglect of all human rights, including the right to life. One of the first researchers of totalitarianism, Vasily Grossman, compared the photos of the children from German concentration camps and the photos of children taken during the Great Famine of Ukraine. They looked identical.

The historian is convinced that the Nazi and the Stalinist systems have to be compared not only in order to be better aware of each, and of the past of the “Bloodlands.” He believes this is necessary in order to understand the present world, our time, and ourselves. This suggests the words of a Soviet poet, spoken of the war memories: “It is the quick that need it, not the dead.” And it is no mere coincidence that the author titled his afterword with a word which his main characters never used, Humanity.