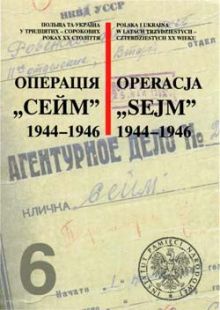

The launch of the sixth volume of the joint publishing project Poland and Ukraine in the 1930s-1940s: Unknown Documents from Secret Police Archives took place recently in the Polish cities of Warsaw and Rzeszow. This volume is devoted to an operation codenamed Sejm, which the Soviet state security organs launched in 1944. Among those who took part in the Warsaw launch were Dr. Janusz Kurtyka, chairman of the Institute of National Remembrance’s (IPN) Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation, and Oleksandr Motsyk, Ambassador of Ukraine to Poland, as well as various academics, journalists, and people who are interested in the complex history of Polish-Ukrainian relations. The launch at IPN’s Rzeszow branch, headed by Ewa Leniart, was also successful and drew a big crowd.

The book launches were not the only events that marked the annual visit to Poland of our delegation to attend a session of the joint Polish- Ukrainian working group. Among the members of the Ukrainian delegation were Serhii Bohunov, director of the state archive of the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU); Petro Kulakovsky, a leading expert at the SBU archive; several more employees of this institution; Serhii Lanovenko, chief of the archives directorate of the SBU’s Odesa branch, who is working on the preparation of the next volume; and this writer.

Our joint group, set up 12 years ago, is engaged in preparing the above-mentioned series of volumes. The Polish part of the group is headed by Piotr Mierecki, vice-director of the Department of Migration Policies at Poland’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration. The group’s Polish members are IPN associates (mostly at the Clearance and Document Archivization Bureau). This year our Polish colleagues did their best to help us enrich our knowledge of Poland, particularly the places associated with the events that are discussed in the joint publication. For example, we visited Bieszczady and covered more than 1,300 kilometers of Polish territory.

We have been visiting each other regularly since 1996 and can thus observe the ongoing changes in our two countries. (Incidentally, Poland is evolving dramatically since it joined the European Union). Obviously, we are pushing ahead with our joint project. The first six published volumes are devoted to the Polish underground in Western Ukraine in 1939-41, the resettlement of Poles and Ukrainians in 1944-46, the role of the Poles and Ukrainians in World War II (the linchpin of this volume is a collection of documents that shed light on the macabre “Volyn massacre” of 1943-44), and Operation Vistula in 1947.

Our working group immediately defined the guiding principles of our work if we really aspired to achieve results rather than engage in endless and boring talkfests on “thorny questions” of the past. One of these principles is this: we make as few personal judgments and reflections as possible and present as many documents as possible, which until now have been inaccessible to experts and the general public. Perhaps this is what has always saved our joint group from fatal misunderstandings, fruitless debates, and reciprocal suspicions and accusations, although, frankly speaking, there are still more than enough historical grounds for this. Be that as it may, the subject of my article is not this but Operation Sejm, the subject of the latest volume of the joint series.

CONCEPT

Operation Sejm was conceived in 1943, when the German occupiers had not yet been driven from Ukraine. Already at that time Soviet intelligence had obtained evidence that the Polish underground movement in Western Ukraine and Western Belarus was showing a tendency toward activation. Its militants had allegedly begun to draw up lists of communists and officials. In addition, the Polish Military Organization (POW) was restored and had become active on the above- mentioned territories as well as in Poland itself. The Soviet side also knew about the eventual alliance between the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and the POW.

In the view of Soviet secret intelligence leaders, all this might create a dangerous situation and adversely affect the situation after the Nazis are expelled. On Nov. 6, 1943, Serhii Savchenko, People’s Commissar of State Security (MGB) of the Ukrainian SSR, sent an instruction to local NKVD units. The document emphasized that “although the defeat of the planned uprising is a foregone conclusion, which even the POW leadership admits, the latter nevertheless maintains that it should be carried out to show the entire world the ‘unwillingness’ of the former population of Poland to accept the Soviet model of government.” The leaders of the USSR and the Ukrainian SSR were informed that the Polish government in exile in Great Britain had sent emissaries to Western Ukraine and Western Belarus to lead the Polish underground and carry out subversive operations.

In his next directive dated Nov. 24, 1943, Savchenko stressed the importance of collecting intelligence data on former citizens of Poland who had settled in Ukraine’s eastern oblasts, as there could be Polish underground agents among them. The directive demanded exposing agents of the Polish underground as well as other foreign intelligence services.

Beyond a shadow of a doubt, Savchenko’s directives were instigated by Moscow. Proof of this is the order signed on Jan. 25, 1944, by the People’s Commissar of State Security of the USSR, Col.-Gen. Bogdan Kobulov. Incidentally, it was my Polish colleague, the historian Grzegorz Mazur, who disclosed this order in 1993. Among other things it emphasized: “With the aim of concentrating all information on the Polish nationalist underground, draw up a centralized file codenamed Sejm in order to collect all materials on all the uncovered nationalist organizations (with a separate chapter on each of them).” Kobulov also demanded that a concrete plan of collecting intelligence about the Poles be submitted for approval to the NKVD 2nd Directorate by Feb. 10, 1944. Such a plan was drawn up, and Kobulov’s order may be considered the first official document that contained the name of the planned operation — Sejm.

On Feb. 29, 1944, Savchenko issued another directive that classified the POW, Stronnictwo Narodowe, Oboz Zjednoczenia Narodowego (OZON), Stronnictwo Ludowe, and the Polish Socialist Party (PSP) as anti-Soviet and dangerous to the Soviet Army’s rear. The directive demanded the detection and arrest of members of these organizations, and the uncovering of their centers and channels of communication with the London-based Polish government in exile. In another document Savchenko informed local NKVD units that the OZON and POW are “the most hostile in their ant-Soviet activities.”

It is obvious that in launching Operation Sejm the Soviet establishment was seeking to solve at least two problems. First, to counteract the policy of the Polish government in exile (which the USSR had recognized in 1941, later breaking off diplomatic relations with it after the Nazis disseminated information about the Katyn massacre), whose goal was to restore an independent Polish state within the 1939 borders. Second, the Kremlin intended to eviscerate those Polish political forces that were trying to keep Poland out of the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence and prevent the communists from coming to power. One of the documents attesting to this is a lengthy directive entitled “On Polish Political Parties and Organizations,” which was approved by Savchenko in April 1944.

Other documents provide grounds for a more detailed understanding of the fact that the Soviet Union had freedom of action with respect to Poland, Polish underground organizations, and the formidable Armia Krajowa (AK) on the territory of Western Ukraine, Western Belarus, Lithuania, and the Polish lands liberated from the Germans not only because it wielded a great deal of military clout. This freedom of action was also guaranteed by the West’s attitude. For example, Maria Rogowska, a member of Panstwowa Sluzba Cywilna, who was arrested in Rivne oblast in 1944, thus explained the motives of the London government in exile: “The reason why those instructions were issued was that the Soviet Union was allegedly forced by the US and Britain finally to tally the number of Poles residing in the western regions. This is why the Polish government is seeking to have as many Poles as possible on these lands in order to bolster its claims to Western Ukraine.”

In fact, there was no such pressure from Western politicians on the USSR with regard to its actions against the Poles. Nor were the Western leaders’ attempts to change the course of events in Western Ukraine and Belarus during the Yalta Conference effective. The conference recognized de facto the right of the Stalinist regime to secure the Soviet Army’s rear in any possible way on the territories that had been liberated from the Germans and, hence, to suppress the Polish political and armed underground.

Documents show that the Soviet secret police carried out certain preemptive strikes against the Polish underground during the initial stage of Operation Sejm. According to a report written by Fedor Tsvetukhin, chief of the Rivne Oblast NKVD Department, and dated June 7, 1944, many of those arrested had not been engaged in direct actions against the communist structures but were waiting for instructions. Yet, the more the Soviet Army moved westwards, the more concrete shape Polish underground organizations were assuming and the more actively the Soviet secret services acted.

IMPLEMENTATION

This is corroborated by the documents that are included in Vol. 6. They should be regarded in the context of the measures that the Soviet Union was adopting to install communism in Poland. The founding of the Krajowa Rada Narodowa (KRN) and the formation of its local branches took place between early 1943 and late 19944. The Soviet Army, which was advancing towards Poland from the east, was accompanied by the 1st Polish Army. In July 1944 Polish pro-communist forces established their executive body — the Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) — which issued a manifesto to the Polish people. The PKWN’s concept radically differed from that of the government in exile. It is only natural that the pro-communist PKWN proclaimed an alliance with the USSR as the crucial point of its foreign policy: the two sides signed an agreement on the Soviet-Polish border along “the Curzon Line” and on the relationship between the Soviet supreme command and the Polish administration.

The Soviet envoy to the PKWN, Gen. Nikolai Bulganin, was vested with broad powers. He was assigned the following task: “No recognition should be granted to any administrative bodies, including those of the ‘government’ in exile, on the territory of Poland; those who position themselves as representatives of these bodies are to be treated as impostors and arrested as adventurists.” The mission was also urged to clear the Soviet Army’s rear “of all kinds of groups and formations of the ‘government’ in exile and armed units of the so-called Armia Krajowa and to monitor the disarmament of the above-mentioned groups and units.”

Therefore, Operation Sejm fits in only too well with the measures that are described in detail in Vol. 6. Most of the cited documents deal with the suppression of the armed and terrorist struggle that was waged by Polish underground units.

The Moscow leadership focused special attention on the killings of Red Army soldiers and policemen by Polish resistance fighters. For example, in a ciphered cablegram to People’s Commissar of the Interior Vasyl Riasny and People’s Commissar of State Security Serhii Savchenko of May 25, 1945, Bogdan Kobulov, mentioned earlier, urged them to immediately report on every instance of the killing of an officer or soldier. These facts were required primarily in order to put the heat on the Armia Krajowa, the most mass-scale anti-Hitler underground military organization in Poland, which was fighting for the restoration of Poland’s prewar borders and the authority of the government in exile.

Quite a few documents describing the activities of the AK’s structures have been preserved, including one concerning the discovery of its Lviv branch in the spring of 1945. A successful struggle against the AK was of great practical importance for the Soviet state security and the entire Moscow establishment. It was the AK, with its roughly 70,000 to 80,000 fighters, who were stationed mostly in eastern and southeastern Poland and on the territory of Lithuania, Western Ukraine, and Western Belarus, that was supposed to carry out Operation Storm. This plan entailed the AK’s participation in ousting the Germans and permitted its cooperation with, but not integration into, the Red Army. AK commanders were instructed to stay behind in the rear of the Red Army, prevent Polish pro-communist elements from seizing power, and ensure the authority of the government in exile. This is why the efforts to counteract the AK, destroy its underground elements and armed units engaged in gathering intelligence, maintain radio communication with the supreme command and the London-based government, airlift messengers across the front line, and commit acts of sabotage, etc., were a crucial component of Operation Sejm.

For the first time we were able to study documents that show the emergence, activities, and destruction by the state security organs of the military and political organizations that emerged after the AK was formally disbanded (January 1945) and whose members were its former fighters. This primarily refers to Wolnosc i Niepodleglosc (WiN), which existed until 1952, although its leadership was repeatedly arrested, and the founding of Wojskowi Zwiazek Samoobrony (WZS). In July 1945 the NKVD in Belarus informed the AK’s Bilo- Podliasky branch that the WZS was to replace the AK and perform the same functions.

Archival sources show that, after the signing of the Polish- Ukrainian resettlement agreement on Sept. 9, 1944, the Polish underground set itself a new and important task: to hinder the resettlement. Tymofii Strokach, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR, pointed out in his directive to NKVD officials in the western regions: “In the last while, the leading circles of the Polish nationalist underground have carried out a series of actions aimed at foiling the evacuation of the Polish population and reinforcing their highly clandestine organizations in the western regions of Ukraine by smuggling in from Poland previously evacuated Polish nationalists, mostly young AK members.”

Strokach explained that the latters’ main task was to spread rumors that those who had been evacuated from Western Ukraine were living in bad conditions in Poland, that AK fighters would wreak vengeance, and that the US and Britain would pressure the USSR into returning the Polish lands — so it made no sense to leave. One of their assignments was to carry out terrorist acts against NKVD-NKGB operatives and collaborators. The Strokach directive demanded that everybody who had arrived from Poland be secretly arrested and interrogated to find out whether they belonged to the underground and, if possible, to use them for intelligence-gathering purposes.

As noted above, the Soviet secret service was especially worried about the likelihood of agreements between the Polish and Ukrainian underground movements. Savchenko noted in the memorandum that he sent on June 5, 1946, to Moscow and the Soviet Ukrainian leadership: “In the course of the liquidation of Ukrainian and Polish nationalist formations in the western regions of Ukraine, the organs of the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR obtained intelligence and investigation data, as well as documents of the OUN and the Polish underground, which prove that the ringleaders of these formations are conducting active negotiations on ceasing the hostilities between the OUN and the Armia Krajowa — the AK — and on uniting and directing these illegal formations against the Soviet power and the Polish Government of National Unity.”

Noting that similar talks had been held in the past (1942-44), Savchenko concludes, “We know of instances when local nationalist- minded Poles made contact with the leaders of the OUN-UPA underground, supplied the OUN illegals with food and clothes, and actively assisted them in escaping prosecution by our authorities.” With this in mind, Savchenko urged the state security organs to launch an active operational and intelligence-collecting effort “to fight and eliminate the remnants of the Ukrainian-Polish nationalist underground.” Thus, to some extent Operation Sejm was assuming an anti-Ukrainian nature.

CONSEQUENCES

Of special interest are the reports and statistical materials published in Vol. 6. They not only show the scale and dynamics of Operation Sejm, but also make it possible to spotlight the priorities of the Soviet secret service. For example, in August 1946 Pavlo Medvedev, chief of the 2nd Directorate of the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR, drew up a report on Polish- related intelligence-collection and operational work for the period from 1944 to Sept. 1, 1946. This document stressed that the main effort was aimed at eliminating the organizations run by the Polish government in exile, including the most influential ones, such as the PZP-AK (Polski Zwiazek Powstanczy-Armia Krajowa), PSC-DR (Panstwowa Sluzba Cywilna-Delegatura Rzadu), NSZ (Narodowe Sily Zbrojne), NOW (Narodowa Organizacja Wojskowa), KON (Konwent Organizacij Niepodlegloscewych), Mloda Polska, the youth organizations Strzelec, Orleta, and others. “The above-mentioned underground organizations,” the report emphasized, “had money, staff, weapons, radio stations, printing machines, and other equipment.” The report also pointed out that a total 108 “Polish anti- Soviet organizations and groups” were eliminated in 1944-46 and about 4,000 people were arrested.

In publishing these and other documents, which are being introduced into scholarly circulation for the first time, we think it is a good idea to draw the attention of researchers to the necessity of a further thorough study of the true role and influence of these and other Polish underground organizations. They should study the extent to which the actions of the Soviet security organs were preemptive and to what extent they were aimed at eliminating organizations and individuals whose struggle against the communist regime had already produced tangible results.

There was one problem. We failed to locate some kind of document that would finally dot the “i” in the history of Operation Sejm. Perhaps other researchers will succeed. However, the available sources give ample grounds to link the final stage of this operation to 1946.

At any rate, one thing is beyond any doubt. The documents published in Vol. 6 allow us to affirm that all the key problems in the organization and implementation of Operation Sejm were resolved in Moscow. Judging by the existing sources, the NKVD and the NKGB of the Ukrainian SSR were simply obeying the orders from Moscow. Although Moscow’s policy towards Poland during the war changed, one fundamental principle was unwavering: the consistent elimination of the representatives and organizations of the Polish “underground state.”

...We were returning from Poland in a good mood, pleasantly surprised by the way contemporary Polish society (which, of course, has no fewer current problems than Ukrainian society) is reacting to historical events. We signed the latest report on the session of our working group and therefore felt that rosy prospects had opened up: the next, seventh, volume of the joint publishing series will be devoted to the Holodomor in Ukraine. Among other things, we will publish materials of the Polish intelligence service, as well as Polish and other diplomatic institutions, which relate to the 1932-33 tragedy. So we can definitely promise that this will also be a unique volume. We are planning to launch it officially this November in Kyiv.

Dr. Yurii SHAPOVAL is a professor of history.