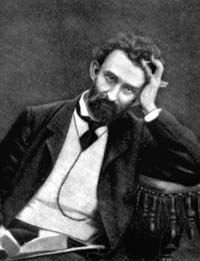

2006 marks the 160th anniversary of the birth of Mykola Mykolayovych Myklukho-Maklai [Nikolai Miklukho-Maklai]. In recognition of his outstanding impact on science, UNESCO commemorated the 150th anniversary of Myklukho-Maklai’s birth by including it in its calendar of memorable dates, which is in itself remarkable given UNESCO’s usual practice of commemorating only jubilees represented by round figures, i.e., those divisible by 100 years. In Ukraine this date passed largely unnoticed despite Myklukho-Maklai’s Ukrainian roots, of which he was proud. The achievements of his short, intense life benefited all of mankind and he deserves to be remembered by future generations of Ukrainians, for his efforts to secure freedom for faraway islanders served as an impetus for the universal crusade against slavery.

A descendant of the legendary Zaporozhian Cossacks, Myklukho- Maklai was an outstanding scholar whose interests touched on many fields of knowledge: ethnography, philosophy, biology, and geography. His many studies on zoology, zoogeography, and physical geography are still relevant today. He made a tremendous contribution to science as a founder and pioneer of marine biology and comparative anatomy. His services to mankind and science have yet to be fully appreciated. Maklai was the first to prove scientifically the biological equivalence of all nations and races. His studies and statements in the press paved the way for the global movement against racial discrimination. He predicted the collapse of the global colonial system, introduced the ideas behind such organizations as the United Nations Organization and UNESCO, and prepared the first draft of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. His dream of an independent Papuan union also came true.

He was an extremely hardworking and focused individual, who was imbued with a sense of duty to mankind since his childhood. Maklai’s father, Mykola Illich, was a Ukrainian nobleman born in Chernihiv province and a descendant of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. Stepan Makukha, Myklukho-Maklai’s great-grandfather, who was nicknamed Makhlai, was appointed khorunzhy [flag-bearer] of the Zaporozhian Host, and the Tsar conferred nobility upon him for his military skills and heroism during the siege of Ochakiv. Meanwhile, Okhrim Makukha, Stepan Makukha’s great-grandfather, was otaman of a Cossack military unit in the Zaporozhian Host. The famous Ukrainian-born writer Nikolai Gogol based his colorful image of Taras Bulba on tales about Okhrim Makukha. In Taras Bulba, Gogol quotes Okhrim’s memorable words, which had passed from generation to generation in the Myklukha family. When he was putting his middle son to death for betraying his younger brother and causing his death, Okhrim says: “Brotherhood is the holiest of ties. A father loves his child, and a mother loves her child, while the child loves his parents. But this is not what matters: even animals love their offspring. Only men can become kindred in spirit and not just through blood.”

These two Cossack forebears were legendary heroes and the pride of the Myklukha family. No portraits of them have survived, yet both of them became embodied in Gogol’s character Taras Bulba whose portrait in oil always stood on the table in the house of Maklai’s father. It is no wonder that Maklai thought of himself as a descendant of Taras Bulba.

Maklai’s father was orphaned at an early age, which circumstance forced him to earn money for food by tutoring during his studies at the Nizhyn Lyceum. After graduating with honors, he dreamed of pursuing a higher technical education. To do so he had to travel to St. Petersburg. With no money for the journey, he covered the distance on foot.

He encountered good luck in St. Petersburg. Hungry, dirty, and penniless, he met Aleksey Tolstoy, who had also spent his childhood in Nizhyn and recognized the young man’s embroidered shirt and cap, the school uniform of the Nizhyn Lyceum. Tolstoy helped young Mykola enroll in the Institute of the Corps of Railway Engineers and rented an apartment for him. Tolstoy subsequently introduced Maklai’s father to Nikolay Nekrasov and Alexander Herzen.

Maklai’s mother, Kateryna Semenivna Bekker, was of mixed Polish and German blood. Her father came to Russia to join the war against Napoleon and remained there to practice surgery. Maklai’s mother finished music school and was preparing to become a professional pianist. She was also a composer and amateur painter. Maklai’s father also had a passion for music and painting.

Eventually, the five Myklukha children, except Serhiy (Maklai’s eldest brother, who devoted himself entirely to the law from the age of 10) had an appreciation for music, painting, and literature.

Even before entering high school, young Maklai and his younger sister Olha compiled two small collections of illustrations for Gogol’s works. Mykola Illich painted landscapes in oil, while Kateryna Semenivna was a skilful painter of charcoal portraits and watercolor landscapes. Maklai’s younger brother Volodia specialized in painting the sea and ships.

On Saturdays the family gathered for literary and musical soirees, taking turns reciting poems to the accompaniment of Kateryna Semenivna, who would improvise on the piano. Their repertoire included poems by Gautier, Mickiewicz, Shevchenko, Nekrasov, Lermontov, Pushkin, and, of course, Tolstoy. Mykola Illich was particularly good at reciting Lermontov’s “Mtsyri” [The Novice] and Shevchenko’s “Haidamaky” and “Kavkaz.”

The head of the family, Mykola Illich, had discovered Shevchenko’s works many years earlier. As early as 1842 Aleksey Tolstoy presented him with handwritten copies of “Haidamaky” and “Kateryna,” and later the poems “Kavkaz,” “Hamaliya,” and “Yeretyk.” While Shevchenko was in exile, Maklai’s father expressed his solidarity with the poet by sending him a postal order for 150 rubles, which cost him his job. At that time he was the administrator of the passenger terminal and railway station in St. Petersburg. This position demanded the utmost dedication to the tsarist government, since the railway station administrator was responsible for the security of the tsar’s train that connected Moscow and St. Petersburg. Suddenly the station’s administrator turned out to be a sympathizer of one of the empire’s most dangerous rebels. The money order was intercepted by the postal service and an investigation ensued. There’s no telling how this would have ended if Mykola Illich hadn’t developed rapidly progressing tuberculosis. His days were numbered.

Mykola’s father did not live to see 40. On his deathbed he asked his family to be brave and spoke to each one of his children. The eldest son, Serhiy, was 13; Mykola was 11, Olha, nine and a half, Volodymyr, eight, and little Mykhailyk, a year and a half old. Despite their young age, the four older children had already decided on their future professions. Serhiy wanted to become a judge, Mykola a scientist, Olha an artist, and Volodymyr a naval officer. Perhaps because of his children’s precociousness, the father chose to speak about their future professions on his deathbed.

“You will have a difficult time, my son,” he told Serhiy. “Law and conscience do not always go hand in hand. Meanwhile, a judge, though a living being with a soul and conscience, must unquestioningly obey the law only. Although this is true, Serhiy, the law also has to be interpreted with the mind and spirit, and judgment has to be passed as the conscience dictates. This is no easy task, but one that a judge cannot escape. Therefore, before you make this decision, think hard whether you will have enough civic courage.”

The father rested after these words and motioned to Mykola: “I would like you, Mykolka, to be guided by the following principle in the future: any thought in science is important and useful as long as it is expected to bring benefit in future life. Man’s thoughts can soar to great heights, but even at such a height one must have a goal that will serve the common good, because science is not for science’s sake but always for the people.”

He then stroked Olha’s hand and held it: “I know, Olechka, that you will honestly serve art. And this is enough — to bring beauty to people.”

Addressing Volodia, he adopted a strict tone of voice: “Now that you have decided to become a defender of the fatherland, you, Volodia, must always remember that its honor is paramount. Let the weapons in your hands serve glory and valor; everything else will come in due course.”

Mykola Illich eyed little Mykhailyk admiringly and said, fighting back sadness: “You, my dear teddy bear, will treasure the truth, won’t you?”

His final words were addressed to his wife: “Forgive me, Kateryna, for I leave you with a heavy burden.”

They say parents can decide the future of their children by using their will to spur them to occupying a certain niche in life or by predicting their professions depending on their skills or personality. Yet no father can influence his children to the extent that these children, all grown up and independent, will subordinate their thoughts and deeds to his influence. Apparently, Mykola Illich Myklukha was an exception to this rule. He did not choose his children’s professions, leaving the choice to them. But he prescribed the nature of their thoughts and deeds. As far as these fundamental and most important human qualities go, none of the five children betrayed their father’s last wishes.

Serhiy Mykolayovych Myklukha became a fair and incorruptible judge in the Kyiv region.

The great scientist Mykola Mykolayovych Myklukho-Maklai devoted his entire life to serving people.

Olha Mykolayivna Myklukha grew up to be a wonderful artist and a person of exceptional kindness.

Mykhailo Mykolayovych Myklukha became a mountain engineer and a champion of the people, following in the footsteps of Sofia Perovska.

Volodymyr Mykolayovych Myklukho-Maklai, 1st Rank Captain and commander of the ironclad battleship Ushakov, died a hero’s death in an unequal battle outside Tsushima while valiantly defending the honor of the Russian flag. The brave commander of the battleship rescued his crew until the ocean claimed him. The captain refused to board a Japanese lifeboat that had come to his rescue. It was filled to capacity and instead of climbing onboard, the commander pointed to a wounded sailor who was drowning nearby.

The Japanese must be given their due. When the Russian battleship was going down, the Japanese cruisers that had been bombing it lowered their flags to half-mast in acknowledgement of the Russian officer’s heroic deed. Nothing could save the Russian ironclad, since the enemy’s two fast cruisers were beyond the reach of the Russian vessel’s artillery, and the Ushakov could neither approach the enemy nor retreat. Although doomed, the Russian crew refused to surrender.

Maklai’s unusual surname surprised many people, and when a newspaper correspondent asked him about his nationality in 1884, Mykola Myklukho-Maklai answered, “I am a living example of the symbiosis of three forces that have been antagonistic toward one another since time immemorial. The fiery blood of the Zaporozhian Cossacks peacefully blended with the blood of their seemingly irreconcilable enemies, the Poles, and was diluted by the blood of the cool-headed Germans. To judge which component is dominant or most significant in me would be inconsiderate and hardly possible. I sincerely love my father’s homeland — Little Russia [i.e., Ukraine]. Yet this love does not depreciate my respect for the two homelands of my mother — Germany and Poland. I don’t believe that I should give preference to any of the three nations that make up my person. Of course, I recognize blood ties and treat them with what I believe to be due respect, but blood composition, in my view, does not determine a person’s nationality. It is important where a person has been raised and by whom, and what ideals have been inculcated in this person. The question is, what should we call a nationality: the biological beginnings or spiritual substance of a person?”

What shaped Maklai’s ideals? His childhood was not happy. It appears that he fell prey to every possible children’s disease. Though doctors claim that children can have scarlet fever only once, Maklai caught it three times, on top of measles, mumps, and jaundice. He suffered frequently from sore throats, chronic pneumonia, bronchitis, and weak joints that were achy from rheumatism that he developed at a young age. He was also troubled by an obscure gum disease and rheumocarditis. Moreover, he stuttered for 12 years and could not pronounce the letter “r” properly.

Obviously, he suffered from frequent abuse in childhood. Mykola could not stand up for himself, but never complained to anybody, to avoid showing his helplessness to those around him. One entry in his childhood diary reads, “It gives evil people double pleasure when they see your weakness and become convinced that their evil hurts you. To give them this pleasure would be unwise, because this is exactly what they desire, believing mistakenly that by hurting a defenseless person they will exalt themselves. But I might be wrong. To build any assumption a person must think first; as regards reasoning, they are mostly worthless and act spontaneously, more influenced by the animal instinct of self-assertion rather than dictates of reason.”

He continues, “Wrong is he who, in hurting someone, sees the triumph of his strength and, hence, the triumph of his persona. Yet these things have nothing in common, since triumph is jubilation. And what jubilation can there be in anger? Anger reveals a nature deprived of a soul that can commiserate with another person’s pain. Hence, he who commits violence can find no benefit in his act, only harm, because instead of the brave lad that he wants to appear to be, people see in him a stupid egoist, who doesn’t realize the stupidity of his position. Therefore, in my view, those who commit violence deserve cold contempt rather than obligatory revenge. But it is not permissible to leave violence unpunished; this would not be a humane approach, but one that would encourage hideous violence. I have not yet considered the different aspects of this problem, but I believe that in regard to the violence that we encounter on a daily basis my thoughts are correct or, I hope, close to the correct understanding of the matter.” Such words could only come from a person who has suffered a great deal or spent a lot of time thinking. Moreover, such a person must be capable of reasoning. Mykola wrote these words at age 10 on New Year’s Eve, 1856.

Physical inferiority is a heavy cross to bear. Consider one more entry in Mykola’s diary: “A lame cripple, Lord Byron became the best swimmer in England as well as an accomplished horse rider in order to prove his superiority to many healthy individuals and command respect from those around him. He also wielded a saber and could hit a bull’s-eye from a pistol while running. Succeeding in these four kinds of sports seemed impossible in his condition, but the spirit overcame the flesh. This prompts the conclusion: a person who passionately desires to achieve his goal is more inspired by spiritual strength than he is burdened by the weakness of the flesh. Therefore, there should always be a goal that motivates spiritual strength. The views of surrounding people, no matter how authoritative, should not be an incontestable verdict.”

Already at age 10 young Maklai knew that he would become a researcher, scholar, and natural scientist. Mykola learned to read at age four and had read countless books by the time he turned seven. He had a fairly good command of Latin, French, and German, and he could also paint and play the piano. But he wasn’t allowed to enroll in first grade because of his generally weak condition and pronounced speech disorder. His parents had no choice but to teach him at home, because even resident tutors had no patience to listen to his stuttering and often punished Mykola. He was very eager to learn and tolerated this abuse. After learning about it by accident, the parents were forced to fire the teachers and teach Mykola by themselves. But they had very busy schedules, and the boy spent most of his time alone.

With time the Myklukha family would become stronger and truly friendly, their life dominated by Maklai and his great ideas and deeds. For the time being, however, except for Saturday nights, when the entire family gathered for the traditional familial soirees, Mykola had his days to himself. He had absolutely no friends and no one at home with whom he could vent his problems. Silent and withdrawn, he lived in his own world. No one was aware of the thoughts that preoccupied the boy. He hid his diary, keeping it locked in his writing desk and hiding the key. As time passed, it was becoming more and more obvious that this solitude was increasingly essential to him. His eyes increasingly radiated a dreamlike calmness.

Little changed in his behavior once he was finally admitted to school. Even though his speech had much improved by that time and he was no longer the victim of classroom bullies, Mykola didn’t attempt to befriend any of his classmates. He didn’t address anybody unless absolutely necessary and didn’t talk to strangers.

The new student remained a mystery to his peers and most of the teachers at St. Anna’s School. Everybody was amazed at the breadth of his knowledge. On the admissions tests he submitted three of his own literary translations: Cicero’s two-page treatise On Duties, translated from the Latin, Voltaire’s novella Candide, translated from the French, and abstracts from Hegel’s works, translated from the German. These complex philosophical works are often a challenge for people with university degrees. It was inconceivable that an 11-year-old boy, who had never been to school, could produce these works translated from three foreign languages. It turned out that he had also read and summarized many works by the historian Pliny. He had read Julius Caesar, Homer, Petrarch, and Schiller, and had memorized Goethe’s Faust in the original German. He could recite many poems by Russian authors, as well as Shevchenko’s “Haidamaky” in Ukrainian.

When it came to Mykola’s talents, there was plenty to be surprised about. Yet his diary shows that on the day of his father’s funeral (December 17, 1857), the bereaved boy locked himself in his room and translated from the Latin abstracts from the works of the Roman poet and philosopher Lucius Seneca, noting down the most important thoughts in his diary. He concluded, “Obviously, Seneca was right. To feel rejected by people without reason is unpleasant and insulting, much like it feels to be punished undeservedly; yet solitude is no doubt good for the mind’s fruitful work. What’s the use of a mind that is always dragged into the whirligig of commotion? Indeed, very little or none at all.”

On that night sleep did not come to him. Hardly had he shut his eyes when he saw his father’s grave and felt the cold of the frozen earth. Recalling that night when he was older, Mykola said, “I was afraid of closing my eyes and to keep myself busy I read Seneca through the night, analyzing what I read. Then I got a new perspective on the issues of life and death. At the cemetery and for a long while afterward I could not rid myself of the feeling of shame and an unhealthy sense of guilt. After all, whenever I wished that I were dead, I was unwittingly wishing to bring misery upon my family. Then I realized something and I still remain convinced that no matter how hard life is, a person has no right to dispose of his life as he sees fit, because it doesn’t belong to this person only, but also to people who are by his side. Meanwhile, if he is a thinking person who is creating or is capable of creating objects of spiritual or material value to society, this person also belongs to all of society. Therefore, to wish oneself dead or to commit suicide is a criminal act because it is an essentially criminal encroachment, whether conscious or not, on other people’s property. On the other hand, it brings misery upon innocent people. Only two forms of death deserve respect: natural death and death caused by the need to sacrifice oneself for some universal, humanistic goal.

“With this realization I never again wished that I were dead.

“As I realized back then, life is beautiful because only life can create beauty. This is its main quality and thus its main significance and sense.

“The sense of an individual person’s life is a different matter. Everybody has their own meaning in life, and all those who want to live a meaningful life should determine what this meaning is in due time and be prepared to sacrifice something in order to achieve their goal, because everything to which we aspire comes at a price. The loftier the goal, the higher its price.

“In Seneca I found the justified need for solitude on the part of all those who want to improve their minds and grasp certain truths. Without constant contemplation in solitude, in silence and calmness, it is impossible for the mind to work fruitfully. In this connection I must note that some people vainly try to read as much as possible and visit all places. According to Seneca, he who lives everywhere lives nowhere. Meanwhile, the mind is improved not by the number of books read, but by the way a person comprehends what he just read, comparing things just learned with things already known, doubting the validity of his reasoning, and trying to find proof of such reasoning or the lack of it. Compared to reading, the process of such comprehension is much more complex and therefore requires solitude.

“Moreover, any personal thought that can be called a thought — this notion is not as simple as it would often seem — is a discovery born of the intimate sincerity of the mind. Yet what intimacy is possible in public?

“Now that over 30 years have passed I can state with certainty: if for the better part of my life I did not control my desire to spend all my time surrounded by friends or simply people who are pleasant to talk to, I would not have accomplished anything significant.”

Later, Maklai’s friend O. Meshchersky said, “Among the people who became dear to me after many years of dedicated friendship I knew only one person that earnestly and seriously cherished and treasured his own time and the time of others, and who never temporized or placed his own feelings or those of his friends above the cause. That person was Maklai.”

Maklai was born for science. He craved knowledge but the path to his dream was full of obstacles. Years later, when a correspondent commented to him, “Word has it that they didn’t treat you kindly in Russia,” Maklai answered, “I was expelled from the sixth grade in high school and banned from attending the University of St. Petersburg, where I was admitted as a free student despite the lack of a secondary education diploma. This is why I was forced to pursue studies in Germany. After my expulsion from the university I could not enroll at any institution of higher learning in Russia, as I was placed under police supervision. This means that Russia itself banned me from studying in Russia.

“I was expelled from high school for reading Alexander Herzen’s Letter on the Study of Nature during Bible class and for bringing Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity to another class.

“At the time I discovered the Bible in the philosophical articles by Chernyshevsky. Influenced by his ideas, in addition to Herzen and Feuerbach, I began exploring the works of Sechenov, Pisarev, Hegel, and the works of Dobroliubov. My mother would always manage to get a copy of Herzen’s clandestine newspaper Kolokol [The Bell]. All of this shaped my beliefs and eventually resulted in my involvement in student meetings and protest rallies. During one such meeting, before my expulsion from high school, my elder brother Serhiy and I were arrested. We were incarcerated in the Peter and Paul Fortress, but I never believed that we were being punished by Russia. Priests and policemen in Russia, much like elsewhere, are part of the state mechanism. Yet even the entire state mechanism cannot be considered to represent the country’s character. When you rise in protest against the existing state system, it is quite natural for people employed by the government to preserve this system to subject you to punitive measures. Yet it would be unwise to direct your anger at the entire country if you have been offended by a single policeman.

“When I say that I belong to Russia, I am proud of this, because I speak about my spiritual kinship with those of its representatives whom I accept and understand as the creators of a genuinely Russian trend in science, culture, and humanism, the latter field being very important to me personally. Yet this is not the kind of kinship that is cause for a familiar get-together at a festive table. This kinship requires everyone who realizes it to maintain constant discipline in their thoughts and deeds. In essence, I do not serve my own idea, but fulfill the program of research whose main direction was established by Mechnikov and Academician Ber. Moreover, in my quest I am guided by Sechenov’s study on brain reflexes and Chernyshevsky’s work The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy. As you can see, all of them are of Russian origin. By the way, I am pleased to say that Russia is the only European nation, which, although it has many different subordinated peoples, has not adopted European racial theories even at the level of the police. Advocates of superior and inferior races cannot find supporters in Russia because their views contradict the Russian spirit.

“As regards Russian science and culture, people who know little about Russia and tend to consider it one of the most despotic countries whose powerless people apparently cannot produce anything meaningful are amazed by the invariable humanism of Russian thought. Indeed, after enduring all the hardships and crawling through thorns, this long-suffering country cannot carry evil within itself. Suffering embitters cold people with venal souls and weak or one-track minds. Meanwhile, Russians are innately passionate and sensitive. When they do get angry or commit violent acts, it is in a drunken state or out of despair. When their minds are clear and they see the root of evil, they never become embittered in their suffering, and their thoughts are not directed toward revenge, which is celebrated and raised to a sacred level in European literature, but only toward uprooting the evil by all means possible, even by means of the same kind of evil. Moreover, Russians are capable of easily sacrificing themselves for other people, who are often strangers.

“Only egotism, not strangers, is alien to the true Russian nature.

“Hence the humanism that is inherent in Russian philosophy. Mikhail Lomonosov, who lived a hand-to-mouth existence for many years and accumulated wealth through hard work, thought only about specific ways for science to benefit thousands of indigent and hunger-stricken people. Aleksandr Pushkin and Mikhail Lomonosov, who themselves experienced the pain of humiliation, could not but sympathize with the proud Caucasians.

“With the exception of Russia, there are few countries in which science and culture, especially literary works by talented authors, that are as single-minded in their purpose.”

The multifaceted knowledge of the 18-year-old Maklai is impressive. In addition to the ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, he was perfectly familiar with the works of the German philosophers, French encyclopedists, English political economists, socialist utopians, and legal scholars. Most importantly, Maklai, who was a keen judge of human psychology, had both feet firmly on the ground and did not permit himself to indulge in any empyrean illusions. Read some of his expressions, and you will grasp the spiritual world of the young Maklai, his quest, the courageous independence of his contemplations and judgments, and, finally, the breadth of his intellect, which both reveals the erudition of the future scholar and allows us to trace the formation of his worldview.

We seem to be present in his spiritual laboratory and, forgetting about the young man’s age, we see an inquisitive philosopher, wise, albeit filled with doubts, who through his suffering seeks a path to the common good. Here is an example of his philosophical writings that have retained their relevance to this day: “If nature is subordinated in everything to a higher purpose and is controlled by the laws of natural development, while mankind is part of nature, do laws of social development exist? What are they derived from? Surely one cannot claim that our whole life is a chain of accidental events. According to Democritus, ‘People invented the idol of chance as an excuse for their own imprudence.’ In reality, if this idol ruled us, the world of humans would be thrown into chaos. Meanwhile, we observe a more or less reasonably established system of families, clans, nations, and states. Since time immemorial there have existed rules of labor distribution, buying and selling, ownership and legal relations, which are typical of all peoples, even though many of them developed independently and did not influence one another in any way (for example, the pre-Columbian states of the Aztecs and Mayans had no ties to the rest of the world).”

With this spiritual wealth the future distinguished ethnographer, geographer, philosopher, and humanist embarked on a path of sacrificial service to mankind, which earned him immortality.