There are certain places that every nationally conscious Ukrainian should visit, among them Chyhyryn, Subotiv, Moryntsi, and Kaniv. The Day has always devoted considerable attention to our national history and these localities, which are its inseparable components. In the opening article of the first book in The Day’s Library Series Ukraina Incognita, authors Larysa Ivshyna and Olha Herasymiuk write that every Ukrainian should visit Chyhyryn at least once. The Day was the first to carry a report of the “Small Town History” series, from Taras Shevchenko’s native village of Moryntsi. It may be no coincidence that Chyhyryn and Moryntsi, as well as many other sites of special importance to the Ukrainian national heritage, are found in Cherkasy oblast. On a map produced by the regional administration these places produce a horseshoe-like pattern. The administration has just launched a tourism project called the “Golden Horseshoe of the Cherkasy Region.” But before this tourism route gets fully underway, much remains to be done. It has all the necessary prerequisites: scenic environs, exciting history — one visit to Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s haunts of Subotiv and Chyhyryn is worth a dozen books, and spirituality, which cannot be created by any amount of investments or bureaucratic decisions, but which exists by itself. Without a doubt, everyone who visits these places will be emotionally touched and bathed in impressions from the wonderful sights. Below are my own impressions of a visit organized by the Tourist Administration of Cherkasy Oblast.

FROM THE HETMAN’S RESIDENCE TO THE PRESIDENT’S

The first leg of our long tour takes us to Chyhyryn. Under the Soviets this administrative district (raion) was considered lacking in prospects, so the locality was spared industrialization; no factories and railroads were built and the road we were riding on was built only a decade ago. So we could fully enjoy the scenic environs. A large road sign reads “Cherkashchyna” rather than the formal “Chyhyryn Raion.” Incidentally, the Ukrainian president’s summer retreat will soon be built in Chyhyryn. The idea was suggested by Deputy Premier for Humanitarian Questions, Mykola Tomenko, and the presidential quarters will be located on the premises of Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s residence. The problem is that nothing is left of the original structure and no one is sure about the exact location and design. The government decided to rebuild Khmelnytsky’s residence and its officials left the hospitable Cherkasy region. But the local authorities have not forgotten about this decision and are expecting the required funds — UAH 67-68 million — to be included in the next budget.

Chyhyryn is the home of the Bohdan Khmelnytsky Museum. Among its exhibits are ordinary items and luxurious objects dating from the Cossack period, including Khmelnytsky’s table, chair, and hetman’s standard. The original flag is in a Stockholm museum and MP Bohdan Hubsky occasionally brings it to Ukraine, along with other insignia. This author saw the flag on one such occasion and I can assure you that the copy is exactly the same as the original. Coins, jewelry, pots, razors, Cossack smoking pipes (mostly made of clay, ornamented, amazingly small and without a tube, signed by their owners; a battle-ax on the handle of which I counted 31 notches, each signifying a kill. In addition to an ax, each Cossack had firearms, a saber, a spear, and 6 or 7 knives serving various purposes. People who have an interest in weapons will find this an interesting exposition. There is a huge saber of Damascus steel with which Cossacks made their deadly upward thrusts.

The portraits deserve separate mention. There are portraits of the hetman and his parents. His father wears an earring and a hat, the same kind that will become an inalienable component of his son’s outward appearance; portraits of beautiful women, the hetman’s wives, among them Hanna Zolotarenko, a young woman who was noted for her strong character; Matrona Czaplinska, a stunning beauty whom Bohdan’s eldest son had executed for her excessive spending during his father’s absence. The hetman’s third wife is older, a solid built woman with a plain face, but she is said to have finally given Khmelnytsky the peace and quiet that he needed.

SUBOTIV

From Chyhyryn we drove to Subotiv. Taras Shevchenko’s stress on the second syllable of the town’s name is actually incorrect. The town is located on the banks of the river Suba, from which the town derives its name. According to another legend, Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s first wife, Hanna Zolotarenko, came from Pereyaslav, which was a large city for the times. When Bohdan brought her to Subotiv she was disappointed by what she saw and said, “Well, it’s subota (Saturday), the last day of the week...” However, the residents of Subotiv prefer the river version and so they stress the first syllable.

Subotiv is located in the vicinity of Kholodny Yar (Cold Ravine) and the place name is explained by the special temperature of the locality. They say that in Subotiv it’s always colder by 8 O C than in Chyhyryn. But it’s hard to tell, considering the constant changes in our weather these days.

And so, “In the village of Subotiv, / Upon a lofty hill...” The hill isn’t all that big. It’s more of a hillock, although it may have been bigger in Shevchenko’s day. It is also true that with his poem about Subotiv the poet saved the local church. Together with other prominent intellectuals he defended the structure that was slated to be torn down for reasons of age and the risk of a cave-in. The church has a long and fascinating history. Its official name is the Church of St. Elijah the Prophet in Subotiv, popularly known as St. Elijah’s Church [Illia]. Bohdan Khmelnytsky funded the construction in 1663. Its architectural style is Cossack Baroque with a hint of Renaissance, as described by Subotiv History Museum director Viktor Huhlia. The church, like all the others in the vicinity, served as a house of God in peacetime and as a fortress in time of war. This explains the thickness of its walls and the height of its windows, along with four loopholes.

The church, which is pictured on Ukraine’s five-hryvnia banknote, is modest but impressive. It is white with green domes. It was empty except for an old woman, who wasn’t pleased by the invasion of media people with cameras and mikes. Near the temple are Cossack graves with large stone crosses bearing roughly carved names and dates of birth and burial. Bohdan Khmelnytsky was interred in the church in 1657. “The coffin with the hetman’s embalmed body stood here,” Viktor Huhlia said with a theatrical gesture, and we had the feeling that he must have seen the casket many times. In place of the coffin is a memorial plaque. The body vanished from the church in 1664 and no one knows how or what happened to it. There are many legends. Polish troops attacked Subotiv in 1664, but the Polish chronicles make no mention of destruction of the remains of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Polish kingdom’s deadliest enemy. People in Subotiv believe that the body was buried elsewhere, but no one knows for sure.

Under the Soviets the church was first converted into a village club, then a mineral fertilizer warehouse, and later into a bomb shelter. When the Germans came, they didn’t destroy the church but made it a functioning house of God. Later they wanted to demolish it and placed explosive charges. The church was saved by a 17-year-old boy, who threw hand grenades at the sappers. He was killed by a grenade fragment, but the church remained intact. The Soviet authorities closed St. Elijah’s Church after the war and its religious life was revived only in the 1990s. “They often ask me if it’s the same church,” says Viktor Huhlia, “and I tell them it is. Why wasn’t it demolished? They tried to but failed. Let me say again that anything can happen in Kholodny Yar.” He is convinced that the locality has a very special, if not magic, aura. From Subotiv we set off to an extraordinary site in the vicinity of Kholodny Yar: a 1,100-year-old oak tree.

SIX HEIFERS AND A COUPLE OF SACKS OF SUGAR

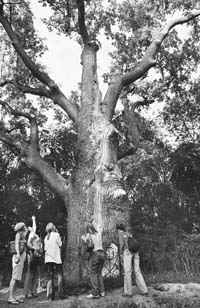

To say that this oak is huge is an understatement. It took seven journalists linking their hands to get around the trunk. The huge tree is fenced off. Surprisingly, it doesn’t look sinister. On the contrary, there is a serene and pleasant touch to it. The tree is a favorite with local residents. Legend has it that if you make a wish, and then walk round the oak three times, it will come true. Another ritual calls for placing your hand on the bark and praying to God. “If you bend your ear to the tree, you can hear things moving inside,” our guide Liudmyla Lemeshko told us. I tried this, but I didn’t hear any voices, probably because there was too much noise outside. However, the main thing wasn’t the result but the process. If people feel like touching this tree or running around it three times, if they want to offer up a prayer in the shade of its huge branches, the way they do in church, and think of something good that they want for themselves, then these people and this tree may well benefit.

There used to be another oak next to this one, its son. Those who don’t know much about botany should know that oaks multiply by acorns, so if an oak strikes root not far the original one, it’s safe to assume that this is its offspring. The other oak withered away several years ago at the age of 700. Its surviving parent has sustained several critical moments: it was struck by lightning 7 times, and began to wither away in 1970, but was revived by Soviet experts. In 2000 the tree seemed to have finally made up its mind to depart this world. It was saved again and in a very interesting manner. A large pit was dug in front of it and then 6 slaughtered heifers, 2 cows, God knows how many other head of cattle, and several sacks of sugar were dumped there. This organic approach yielded the desired effect. You can see that the oak is very much alive. It is named after Maksym Zalizniak. It is believed that Haidamak leaders held their most important councils beneath this oak tree.

The last stop on our route that day was a lake near which Peter Tchaikovsky is believed to have composed his libretto of the “Dance of the Little Swans” followed by the famous ballet Swan Lake. True, there were no swans in the lake, only frogs — a lot of them — and they offered up a gorgeous polyphonic performance. For those who are skeptical about the beauty of frog singing, my advice is to visit the Cherkasy region.

We were brought there to be initiated as Cossacks. The most fascinating event on the Kholodny Yar route is watching hordes of people swearing allegiance to Ukraine, whereupon each and everyone takes the pledge. Those who want to would approach the osavul cavalry captain and he would ask in a ringing voice, “Do you believe in God? Do you drink horilka [whiskey]?” Everyone replied in the affirmative, with varying degrees of confidence. Then each person was offered a small glass of samohon moonshine balanced on a saber blade, a procedure that took some acrobatic skill and athletic background. At the end of the ritual the mustachioed osavul and the novice would kiss each other on the cheeks three times.

A CABIN AT THE VILLAGE’S END

After our visit to historic Cossack sites we were taken to places with famous literary associations. Taras Shevchenko was born in Moryntsi, a village in what is now Cherkasy oblast. The original village house, a cabin, where this historic event took place, is no longer there. An exact replica was erected on the site toward the end of the last century, along with Taras’s grandfather’s cabin. Between these two structures stands a statue of young Taras facing a primary school. The poet’s home is an ordinary Ukrainian khata, its interior fragrant with marigolds and other plants, with small windows and doors through which you cannot pass without bending your head. The yard is more interesting because whereas the cabin is a replica, the earth is the age-old soil. I took off my shoes and walked around barefoot. Young pupils from a grade school in Obukhiv were being escorted on a guided tour. They were enchanted by what they saw. Why did they like the place so much? “Because here everything reminds us of Taras Shevchenko,” explained Olena Danylenko. Apparently the younger generation is taking an interest in our classics.

We left Moryntsi for Kerelivka, where young Shevchenko spent his youth. The village was later named Shevchenkove. On the site of his parental home is a museum and behind it a footpath leading to his mother’s grave. Kateryna Boiko wanted to be buried next to her house, not in a cemetery, “So my children won’t forget the way to my grave, so they can visit it and mourn their orphan’s lot.” Her last will was honored. Her children did visit her grave, as Shevchenko’s poetry makes clear. The grave is marked by a Ukrainian Orthodox cross with rounded ends, and there is a guelder rose bush that was planted when Kateryna was interred. The place is very quiet, except for birdsong. The grave stands at the edge of a ravine, beyond which is the pond glorified by the poet. This plot of land once belonged to the Shevchenko family. Don’t be surprised that a serf could own so much land. The explanation is simple: it wasn’t listed as farmland, meaning it had no real value. The serf Hryhoriy Shevchenko had very little arable land.

We left the grave and headed for the museum. The exposition was traditional, featuring household utensils, clothing, photos, drawings, a bench and a table from Shevchenko’s home — and of course, portraits of the women he loved, along with a great many photos of his descendants, the children of his brothers and sisters. Some 300 of his descendants live in Shevchenkove alone. On display is Shevchenko’s father’s gravestone with an inscription carved by Taras, together with a portrait of the great poet done in flat stitch embroidery. It is a spectacular likeness: some of the visiting journalists said the poet’s eyes were following them around like Mona Lisa.

Hryhoriy Shevchenko’s cabin is at the end of the village, a short walk from the house of the sexton, to whom young Taras would bring fresh water and where he obtained some of his elementary education by listening in on the lessons being taught inside. The cabin is still there, but no visitors are admitted. It is covered by a special structure with big windows through which visitors can see the thatch-roofed khata; it is white and small, with tiny windows and doors. Taras Shevchenko’s last milestone of his youth was working as a kozachok running errands for Herr Engelhardt, the landlord. The latter’s estate has survived the ravages of time, along with a mill where the 13-year-old Taras herded lambs, and the oak tree in which he hid his earliest drawings.

KILL THE ENEMY AND WIN GLORY!

Our next stop was Korsun-Shevchenkivsky. First we were taken to the local history museum, where we saw a variety of exhibits ranging from mammoth bones to Orange Revolution paraphernalia. We saw an ancient grand piano, portraits of heroes of “socialist labor,” and a picture frame made from WWI cartridges — this is the most original item I’ve ever seen. Our next stop was at the museum dedicated to the Battle of Korsun- Shevchenkivsky, a major WWII battle. Located on the premises of a palace built in 1787-1789 and completed by Prince Lopukhin in the 1830s-1840s, the result is a cross between the Russian romantic and neo-gothic styles. Our guide explained that they tried to portray Soviet and enemy soldiers as best as they could. “They look so lifelike,” a fellow journalist from Poltava marveled, gazing at the photos of German officers. They did look lifelike, and some were handsome.

Next are photos of Soviet officers and men, as well as some personal effects, like those belonging to the partisan O. Mishchenko: a neatly folded ragged gray T-shirt stained with blood, indicating that he was tortured; he managed to send the shirt to his mother the day before being executed. There is also a fragment of a letter that starts with the words, “My Dear Mom...” and next to it a regular Killed in Action notice that the soldier’s mother may have received together with her son’s letter.

There is also a spoon and fork set. Joined by a single screw, both utensils are too big and clumsy to handle. Among the other items are an embroidered blouse belonging to a girl who baked bread for a Soviet army division; a travel chess set, with a board that rolls up into a tube; and a complete sets of gears for Soviet troops and Wehrmacht soldiers. Getting back to spoons, there is a large metal one with the names of places visited by the owner, engraved in a tiny and graceful font. “This spoon has been in the western oblasts of Ukraine, Finland, Bessarabia, Ternopil, Proskuriv, Zhytomyr...” plus a dozen other populated areas. Another interesting item is an amber smoking pipe shaped like a chicken leg.

Next we were shown into a large hall where princes once danced. Its walls are covered with Soviet and German propaganda posters reading, “Fire Your Gun, Every Shell Means a Destroyed Enemy Tank!”, “Kill the Enemy and Win Glory!”, “Napoleon Lost His Battle Here, So Will Hitler!” (with a cartoon underneath portraying Hitler in Napoleon’s shadow, bent over from Soviet blows). Surrounding the palace museum is a beautiful, large park with lilacs that blossom in the springtime. It is extremely pleasant in the summer, too.

ON TARAS’S HILL

We were in Kaniv, on top of Chernecha Hora Hill. In his last years Taras Shevchenko dreamed of settling down in Kaniv. The last words he spoke before dying were, “Get me to Kaniv!” After bureaucratic and other delays his body was brought here. The poet found his last repose on top of Chernecha Hora.

The route to the hill passes by the grave of Ivan Yadlovsky, the man who tended the poet’s grave since the burial date-from 1884 until his death in 1933. Yadlovsky’s grave is on a crossroads, with one path leading to Tarasova Hornytsia, the first Shevchenko museum set up by local residents, which features contributions sent by various distinguished individuals. Ivan Repin, for example, painted a portrait of Shevchenko specially for the museum, which resembles an ordinary 18th-century village home, with walls decorated with wreaths made of flowers picked from Shevchenko’s grave at different periods. There is a guest book dating back to 1893. Today this book runs to many volumes. The earliest entry belongs to the prominent Ukrainian composer, Mykola Lysenko. The fragrance of marigold is also present here.

We climbed to the top of the hill to pay homage to Taras Shevchenko’s grave. From there we could see “the fields, the boundless steppes, / The Dnieper’s plunging shore...”

There were many people and many wreaths.

THE MAMMOTH HUNTERS

Mykhailo Ishchenko, a local history buff, told us several interesting stories. The first one was about mammoths. A primordial mammoth hunters’ settlement was excavated not far from Kaniv. These hunters must have been intelligent and hard-working, as 44 mammoth skulls were found on the sites of their five houses. In fact, their homes were built of mammoth skulls: four skulls per house, with the walls and ceilings reinforced with mammoth tusks, and an extra skull serving as an entry to the “guestroom.” In a word, it’s the kind of architecture you have to see for yourself, for it defies description. The first of these houses was transferred to Kyiv’s Museum of Paleontology and copies of it are on display in museums in Paris and New York. The idea was suggested to create an open-air museum on the original site, where all five of the primordial hunters’ homes and other finds would be put on display under the open skies. In fact, certain budget appropriations were made. But the idea was conceived during the perestroika campaign and it died while the Soviet Union still existed. It was considered again after Ukraine became independent, and efforts are being made to breathe new life into this project.

On the top of the hill Mykhailo Ishchenko told us the dramatic tale of Oleksa Hyrnyk, who killed himself out of love for Ukraine and hatred of its oppressors. On the night of January 21, 1978, he climbed to the top of Chernecha Hill and tossed heaps of leaflets as a sign of protest and in honor of the anniversary of the founding of the Ukrainian National Republic. In the leaflets he described Ukraine’s tragic predicament. Then he doused himself with four liters of gasoline, put a lighter to his heart, and flicked the little wheel (Mr. Ishchenko has the lighter and he shows it to anyone who wants to see it). When his body caught fire he walked in a semicircle, probably wishing to take a last look at the Dnipro, and then fell and died. His son is a parliamentarian at the Verkhovna Rada. Mykhailo Ishchenko has written a book about Oleksa Hyrnyk.

* * *

These are just some of the marvelous sites that comprise the historical and cultural attractions of the Cherkasy region. The Golden Horseshoe tourism route is expected to include Sofiyivka in Uman and several other locales. The Golden Horseshoe wants to be recognized at the highest official level. “We believe that this project has a great future in terms of spirituality and business opportunities,” says Mykola Lysuk, first deputy chairman of the regional state administration. “We know, of course, that at this stage we are faced with two problems: lack of information and an underdeveloped infrastructure. Yes, we have hotels and tourist accommodations, but they are inadequate. Our scenic environs can’t get us the kind of tourist business we want. We’re negotiating deals with Ukrainian and foreign investors. We’ve made several serious arrangements, but they’ll work only when this program is accepted on the national level.” Funds will be spent on developing a tourist infrastructure and “condensing” the attractions of Cherkasy attractions — in other words, reviving the folk crafts and folkways of past centuries, and establishing a few more museums. There are many projects in the offing.

Today, the Cherkasy region is ill-equipped to cope with a tourist influx. But you can visit the area and stay in some of the towns or rent a room from a rural resident. You can order a guided tour or view the sights by yourself. Either way, the wonderful local environs, spared the horrors of Soviet industrialization, are well worth visiting.