Ihor KOPOTIYENKO, Candidate of Science in History; Chairman, Dnipropetrovsk Association of Researchers of the Manmade Famine and Genocide:

“The manmade famine left an indelible imprint in my mind, although I was a six-year-old child at the time. We lived on the outskirts of Dnipropetrovsk, and every day we saw cartloads of corpses being carried to the mass burial ground near Sevastopol Park. At that time, there was a low-lying vale there next to the railway station. By all accounts, the bodies brought here were those of the people who had fled the countryside to the city in search of at least some food. I remember mother say in a shaky voice, looking at the carts full of dead bodies, that these were our bread-winners. But, in fact, people avoided speaking on this subject at the time and later. For example, I do not remember any of my colleagues at Dnipropetrovsk University’s Department of History ever starting a conversation about the famine — in all the years of Soviet power — although they came from the countryside and must have witnessed those events, judging by their age. I can recall just one instance when an acquaintance of mine was unwary enough to mention aloud the 1933 tragedy. He was soon summoned to the KGB for a heart-to-heart. Later, during Gorbachev’s perestroika, I worked in the archives, discovering one vivid picture after another. For example, sifting in the archive of the regional public health authority, I found evidence of cannibalism. A woman, who went mad from hunger, killed and salted her own child. There were plenty of such things. What drove those people mad were the conditions created by the Communists. Frankly, a true history of the manmade famine is still to be written. I am convinced it was sheer genocide. Researching the manmade famine, I came to some broader conclusions, and now I am writing, health permitting, a book on the historical destinies of the Ukrainian nation which has undergone all kinds of ordeals in the course of its history.”

Liksandra LAVRENIUK, born 1918, resident of village Vorobiyivka, Polonne district, Khmelnytsky oblast:

“We were father, mother, and five children. Three kids died in ‘33. Father also died of starvation. I don’t even know if my dad’s body was buried at all. Little Danylko was crawling near the stove. When I was lighting the oven, he was reaching out for the fire. ‘Stop!’ But he kept reaching out because he was hungry. So he died, too.

“Brother Zakhar dug a grave for Danylko. He carried him under his arm and buried him. Zakhar was more or less active, he still worked, but he too collapsed in the end. He was once walking across a field of either barley or oats or rye, and he fell and died. A woman from a neighboring village said, ‘I took the shirt off him and bound his jaw because his mouth was wide open.’

“Denys, a neighbor of ours, had been dead for two days, and there was nobody to bury him. He was our cousin, and his three brothers also died of starvation. Somebody came to us asked mother, ‘Shall we bring Zakhar here or bury him over there?’ Well, a mother is mother. ‘Bring him here,’ she said. A cart came over, they unloaded Zakhar as well as Denys. Then they dug a hole. I don’t remember who did it.

“The next day sister Hapka said, ‘Mom, tomorrow I won’t be able to walk and talk. Mom, tomorrow I will die. Please go somewhere again and ask for bread. This is the last time I ask you this.’ Mom wept because she was losing her children and must still be strong. So she says, ‘Oh, Lord, who will give me any bread when everybody is dying?’ And I said, ‘Stop moaning! You’re going to die tomorrow and I today.’ She died that evening. My granddad also died of hunger. Or take Maksym, a neighbor of ours, nicknamed Halaiko. He caught a frog in the river and sank his teeth into it, still alive. The frog was bleeding like hell, but he ate it. Then he came to the hospital and asked, ‘Give me a glass of milk and some bread, I am sure to survive...’ But he died...”

For reference. As The Day was told by Dr. Petro Yashchuk from Polonne, Khmelnytsky oblast, who polled 360 survivors of that tragedy, the 1932-1933 famine claimed 15,000 lives, a fourth of the district’s population. Mr. Yashchuk added, “4,500 Polonne district residents were killed during the Second World War and another 7,500 fell victim to Stalinist repression.”

Halyna MIROSHNYCHENKO, pensioner:

“I was twelve in 1932. I spent four hours a day at a vocational school classes and another four hours working at a public cafeteria. Then I was transferred to a Kramatorsk factory cafeteria. This in fact saved me in those hungry years. I was small and thin as a rake. I was weak but still had to push around heavy caldrons. There were always leftovers in the dining-room, such as cereals or soup. Besides, I was entitled to a kilogram of rationed bread. I several times smuggled the bread out to sell it at a marketplace, but each time I had it taken away. Bread was then worth more than money, you could even be murdered for it. People starved to death. My mother abandoned me, and I lived at an orphanage for a few years. Once somebody gave me my mother’s new address. After the dispossession of the kulaks, she and her new family, including children, moved to some other village. I went there. I came into the room and saw mother with terribly swollen feet and legs. It pained her to stand up. Her two grownup sons and husband lay motionless on a bench, recovering strength. Another son had already died by the time. Mother made a great effort to crawl out of the house, pluck some nettles, and cook gruel out of it. I brought in some bread. Once they saw it, they shivered, speechless, reaching out their hands. Mother began to slice the bread. For if you eat up a big morsel after starvation, you can even die. But the men crazily rushed to wrest the bread out of her hands. They said later I had saved them with that bread. We survived that famine. But then came the war followed by another famine in 1947.”

Nonna KOPERZHYNSKA, Ivan Franko Theater actress. Reminiscences about her were published by the newspaper Donbas on May 3, 2003:

“Nonna Koperzhynska’s father was sent to work in the Donbas in the early 1930s. The Donbas lived through the 1933 famine a bit easier than the rest of Ukraine. This industrial region was supplied with rationed food. Koperzhynska recalled many years later that her mother would pierce a tiny hole in a ration can and, for want of oil, drip the gravy onto the frying pan. Sometimes local residents helped, bringing dried fish and some roots... Little Nonna once saw a handful of apricot stones, crushed them and ate the kernels... She was poisoned so bad that doctors had to make an all-out effort to save her life. But, in spite of the sweeping famine, Nonna was unable to understand the sheer horror of the calamity that fell down on the country; she saw hundreds of refugees from other regions of Ukraine and Russia, who begged for any kind of food.”

Incidentally. As of today, there are three monuments to victims of the manmade famine and political repression in Luhansk oblast: in Novoaidar and Svatove districts as well as in Luhansk itself. The Luhansk Oblast State Archives continue to collect documents for the book Archival Research in Luhansk Region. Special attention is being paid to the documents that were previously hidden, including those relating to the 1932-1933 manmade famine. Although Donbas suffered from the famine to a lesser extent than Ukraine’s other regions, historians still claim the mortality rate here was 3-4 times the usual level.

On November 22, a requiem rally was held in Luhansk dedicated to victims of the manmade famine.

Vasyl NESTERENKO, pensioner:

“I was just a boy at the time, but I remember very well that there was famine in our village. We ate everything and even tried to cook father’s leather boots. Do you know what saved me? My favorite dog — big and red-colored. When dog and cat catchers came to our village, I hid him in a barn for a long time, telling everybody that he had run away. Then I got sick. Mother eventually found the dog in the barn. She fed me with meat, but I didn’t know whose it was. Later I came across some hide and understood everything. I cried. No wonder — I hadn’t yet turned ten. The fact that people were dying of famine in the neighboring houses didn’t seem so terrible. But the soup made of Old Red left a lasting impression. It still chokes my throat.”

Ivan YAMKOVYI, doctor, born in the village of Bilylivka (now Ruzhyn district, Zhytomyr oblast, a chernozem black-soil area) and now dead, was a friend of Mykola Biloshytsky, father of my, Valery Kostiukevych’s, wife, wrote in the book Genocide in 1999 in Zhytomyr and based on archival documents and accounts of the 1932- 1933 manmade famine:

“A terrible famine also swept over Bilylivka. I was preceded by considerable preparatory work: first, the peasants were stripped to the bone via collectivization and dispossession of what they had earned over many years; secondly, special squads were formed to seize food from the peasants. These brigades, headed by so-called plenipotentiaries, consisted of village activists and all kinds of scum. They would go from house to house, make searches, prowl around the yards, barns, sheds and attics. They would probe the ground with sharp prods in search of grain and foodstuffs. They would scoop everything out of the cellars, including the chaff with some remnants of grain. People hid bags with grain behind icons and in oven pots, but the experienced rascals from those brigades would find them even there. Vasylko Yamkovyi’s father, nicknamed Pohorily, spilled a few glassfuls of rye into the boy’s pants and sat him on the couch. One of the activists, Likarchuk, found this stock, pulled the boy’s pants down and shook the grain loose.

“By the spring of 1933 our village wash fully in the famine’s grip. People began to die — first the children, then the old, and then all the rest. As soon as the snow melted, people began to dig up their vegetable gardens, hoping to find at least a few rotten potatoes, and to pick goose root and sorrel. They began eating dogs, cats, and even rats, and looking for mollusks in the rivers Rastavytsia and Sytna.

“As time went by, more and more people got swollen. People looked silent and gloomy, they were trying to avoid seeing and, moreover, speaking to even their kinsmen, they were indifferent even to the dead. Whoever starved knows this horrible sensation when your are haunted by the only thought of putting something you can eat in your mouth. In this situation, the human body usually draws hundreds of defensive forces from its energy reserves, but there were none of them left then.

“The Kostiuk family had been deported to Siberia as kulaks, but their four children managed to stay behind in Bilylivka with their grandmother. They would go to the forest to collect ants. The latter were then put in a tight little bag and cooked to make soup.

“Cockleshells were a great delicacy. We would pick them in the river, make a bonfire, and bake them, but we ran out of them very soon, too. The terrible famine affected one way or another almost all the households. All the Kostiuk children suffered from tuberculosis. Two of them died.

“Bilylivka old-timers Fedora Kotelianets and the late Andriy Kyriy polled the local people to find out how many lives the manmade famine claimed on just two streets — Khursivka and Sloboda — of the village. The results made one’s hair stand on end: on these two streets alone, the famine took the toll of 136 people, completely wiping out 19 households. And there were more than ten such streets in the village. The families of M. Smolsky and H. Zulykha lost 5 and 7 people, respectively. Completely extinct were the families of K. Tkachuk (5), L. Kvasha (6), P. Kyrylyshyn (5), M. Kozina (4 males), and Yamkovyi {not Yamkovyi’s father} (5).

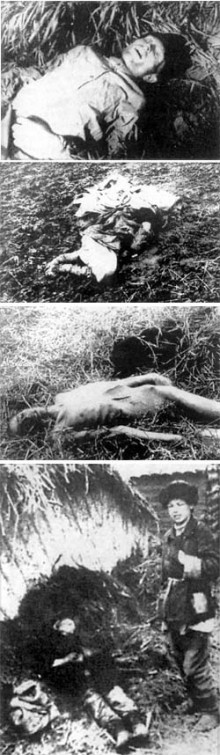

“Thus, in 1933 alone the famine claimed 850-900 human lives, a fourth of the village’s population. Each street had a vehicle to evacuate corpses. The driver was rewarded for this work with 400 grams of bread. All were buried at the cemetery in a large mass grave. Many times there were people still alive among those brought in.

“You can well imagine the mental and physical condition of the parents whose children die one by one, asking for something to eat. The undernourished and swollen mothers were short of milk: when a mother died, so did the infant, often still in the womb. Hryhory Kotelianets lost five children, only one boy, Ivan, remained alive. He grew up and worked at the collective farm as a truck driver, building what was trumpeted as the happy life — socialism and communism — for their fellow countrymen. Many people could not bear such sufferings and went crazy. The deserted houses and estates were given to the homeless. Yet, it was not so easy to pay the tax on this estate.”

P. M. ANDRIUNKIN, teacher, born 1913 (quoted from the Cossack newspaper Stanytsa, No. 34):

“It was announced that a counterrevolutionary plot was being hatched in our village Novoderevyanivska, so we were blacklisted. The Yeisk Regiment was alerted: they cordoned off the whole village: no way in, no way out. All the grain — wheat and corn without anything left — was taken out of the field and heaped on the threshing-room floor. It later rotted down on the ground. Soldiers kept door-stepping and forcing everybody to go to work in what he or she was wearing. They didn’t even allow them to put on proper clothes. Meanwhile, a special commission of activists cleared yards of all foodstuffs they could find, including squashes, beets and even the wheat from the glasses in which candles stood. They would even pour oil out of icon lamps, take out and break jam and pickle jars, leaving all this to freeze on the ground. They would even rob us of the small sacks of peas and beans that we stored for the spring sowing campaign.

“And God forbid they found some old photographs of Cossacks — they would immediately put this person away, saying: oh, you are looking forward for the Cossack atamans to come back, you don’t like Soviet power! So our granny took all the family photos out of the trunk and buried them someplace in the garden. Then she died of hunger. Other old people told their kin to bury them with precious photos on their chests... People died like flies. A team collected corpses, laying them — shrouded in a coarse cloth or just like that — in a big hole and putting a layer of earth over them. Some buried their kin right in the yard.

“I taught at the Otradovka school. I applied to the North Caucasus NKVD chief, who had just come from Rostov, for a pass to my native Cossack village — I wanted to take my mother out. He grudgingly agreed because it was not allowed by regulations. The pass was valid for both exit and entry. While I was en route, the pass was checked so many times. Besides, here in the village, our locals cry out on every street corner, ‘Pass!’ Just fancy: I know him, he knows me but still shouts! So I flipped him the finger and, while he is about to whip out the pistol, I shoved the pass under his nose. ‘How dare you, you snake in the grass, demand a pass from me?’ I said. Later on, after the famine and even after the war, when I came back, I saw those types again.... ‘What did you, scum, do at the time?’ ‘We were forced to...’ ‘Who forced you? You curried favor, you bastards!’ Out of the original 20,000, fewer than 8000 survived in my village. Still, no counterrevolution was found.”

INCIDENTALLY

A rally to honor the memory of victims of the manmade famine and political repression was held in Donetsk at Rutchenkivske Field. The venue was chosen deliberately: it is here that archeologists unearthed a gigantic burial ground in the late 1980s. Different estimates say that this place hides the remains of about 10,000 people who died during the manmade famine. Perhaps the corpses were brought here not only from Donetsk oblast but also from all over Ukraine. Moreover, the grave also contained the victims of political repression, who were shot en masse in the 1930s. The remains of adults mingled with those of children. The rally gathered the people who survived the events of those terrible years.

Activists has so far reburied only about two hundred. A commemorative stone was put at the place where the mass grave once was. “The authorities think it their duty to put the place in order and erect a monument. This should never happen again on our Ukrainian soil,” Donetsk Mayor Oleksandr Lukyanchenko told the rally.

Mykola HORDIYENKO, Candidate of Sciences in Philosophy, instructor at Ukraine University (Dnipropetrovsk):

“Although I was born after the war, I in fact grew up, listening to the stories of how the 1933 manmade famine affected our family. My mother was twenty at the time, and she had already had my elder sister. Father worked at a Pavlohrad construction project, receiving rationed food, which helped our family to survive. At the same time, half the residents of our village of Bohuslav starved to death. As my mother told me, malnourished people would get swollen and fall down right on the street. The dead were picked up by Communist Youth League (Komsomol) squads. In some cases, to spare themselves extra effort, they would take people still alive to the cemetery also to be buried in mass graves. These graves, as a rule, bore no crosses and in time grew over with grass and got lost. Besides, the war that broke out eight years later and brought new woes, famines and mass death must have pushed the 1933 manmade famine in some way to the background of people’s memory, Yet, they could never forget that cataclysm. In addition to claiming the lives of many of our kin, the manmade famine echoed in our family in the 1960s, when I traced my cousins who had been lost after their mother’s death in 1933. I find it hard to explain why the manmade famine was passed over in silence for so many years. It would be perhaps wrong to put this down exclusively to fear of reprisals. Quite possibly the famine had a certain dramatic impact on the mass psyche. For example, war veterans are also taciturn and do not like recollecting people’s sufferings and deaths. In any case, a true study of the manmade famine, the greatest ordeal the Ukrainian people went through, is still to be written.”