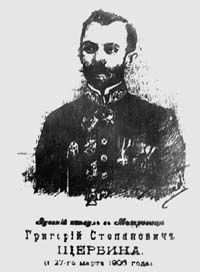

A hundred years ago, the death of two Russian diplomatic officers in Serbia and Macedonia brought Russia to the verge of war with Turkey. Both diplomats, Grigory S. Shcherbina, Russian Consul to Kosovska Mitrovica, and Aleksandr A. Rostkovsky, Consul to Bitola, were of Ukrainian descent [e.g., their names ought to be spelled accordingly: Hryhory Shcherbyna and Oleksandr Rostkovsky]. Documents received from the Russian Foreign Ministry’s archives, courtesy of the Russian Embassy in Kyiv, allow us to learn more about our distinguished compatriots.

Events in the Balkans at the turn of the twentieth century attracted political attention the world over. The role of the Russian Empire in the conflict between Turks and Slavs is hard to overestimate. A Russian official statement of February 12, 1903, read that the Slavic states have every reason to expect the Imperial [Russian] Government to show constant care for their actual needs, and on the powerful protection of the spiritual and vital interests of the Christian populace of Turkey. Simultaneously, they [the said Slavs] should not overlook the fact that Russia will not let a single drop of blood of her sons be shed, just as she will not allow sacrifice the slightest part of the gain of the Russian people, should the Slavic states, counter to the considered recommendation timely forwarded to them, deem it necessary to resort to any revolutionary endeavors aimed at forcefully altering the existing regime on the Balkan Peninsula.

Blood was shed quickly, as it turned out. The tragic news was received in a month; on March 27, 1903, Hryhory Shcherbyna, Russian Consul to Kosovska Mitrovica, died of a mortal wound. The newspapers had hardly switched to other news, after carrying morbid details and reporting on the state funeral and expressions of sympathy, when the world learned of another tragedy. Oleksandr Rostkovsky, Russian Consul to Bitola, died at the hands of a Turkish gendarme. The murder nearly caused Russia to declare war on Turkey; a Russian naval squadron was dispatched from Sevastopol, headed for the Bosporus. Russian analysts wrote at the time, “...our Consuls Shcherbyna and Rostkovsky paid with their lives for carrying out their duty as both Russian citizens and champions of downtrodden Christians.”

Both had followed different paths leading to the diplomatic career. Hryhory Shcherbyna, son of a cabinet maker from the provincial town of Chernihiv did not seem to stand much of chance as a career diplomatic officer. Yet he had talent and determination. So after finishing the men’s classical gymnasium of Chernihiv, he was enrolled in the famous Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages in Moscow. He graduated with honors in 1889 and continued to study at the Asiatic Department of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. After defending a thesis (in Turkish), Hryhory Shcherbyna was appointed attache with the Russian Embassy in Constantinople [currently Istanbul]. The young man then knew sixteen languages and was resolutely climbing his career ladder. In 1897, he was made Vice Consul in Upper Albania (Kosovo). In late 1902, he was appointed Russian Consul to Serbia.

In the spring of 1903, the situation in Kosovska Mitrovica, venue of the Russian Consulate, had acquired a complex political coloration. Shcherbyna was conducting talks with Islamic Albanians and it seemed that the Albanian-Serbian conflict would soon be settled peacefully, yet events took a different course. Hryhory Shcherbyna tried to save several Serbian families during an armed conflict, allowing them refuge on the consular premises. The Serbian refuges were chased by an enraged Albanian crowd attacking the consulate and mortally wounding the consul. The Serbian king, on learning of what had happened, dispatched his personal physician, but it was too late. Shcherbyna’s friends said he must have foreseen his untimely end, telling them before leaving for Constantinople, “I am off to Mitrovica and God only knows if I can make it back. Should I die there, it would cause important consequences. Events might take a course when you would have reason to say finis Turciae [Turkey is finished].” Subsequently, Shcherbyna’s obvious support of the Serbs would prompt a British woman journalist to write that he had got involved in a local unrest of his own free will and should be blamed for what happened after. Shcherbyna’s friend Jovan Civic, a Belgrade professor, spoke of him with utmost sympathy after his death, noting his broad world outlook, rare energy, dedication, sincerity, and genuine religious affiliation.

Meanwhile, the tragic news reached Chernihiv. Hryhory Shcherbyna’s parents asked permission to have the body transported to their native land. An express train arrived in Chernihiv on April 12, 1903. The coffin, draped in the consular flag, was transferred to the Monastery of the Holy Trinity and Saint Sergius, the ceremony attended by a great many people. Some fifty wreaths were placed on the grave, among them ones sent by the King and Queen of Serbia, Russian Foreign Ministry, Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages, Constantinople-based Russian Ambassador to Serbia and Macedonia, residents of Chernihiv and Sevastopol, and many other individuals. The Serbian government decided to name a Belgrade street for Shcherbyna. One can only wonder whether that street is still there.

Four months after the violent death of the 35-year-old diplomat, the world public was stunned to learned about the murder of Oleksandr Rostkovsky.

Archives, newspapers, and books allow us a closer look at his life and endeavors. He was born October 18, 1860, to the family of Colonel Arkady F. Rostkovsky, then commander of the Second Grenadier Division, retiring as major general. He arranged for his son be enrolled at the Imperial Lyceum named for Tsar Alexander, the former Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum. After graduating in 1883, Oleksandr Rostkovsky and five other graduates were assigned posts in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Shortly prior to the appointment, Oleksandr had met a girl, Princess Katerina, a graduate of the Smolny Institute. They had fallen in love, married, and traveled abroad. Oleksandr was appointed second secretary with the diplomatic mission and consular office in Bulgaria. His charming wife would be admired by everyone wherever he had to work from then on. His next post was that of secretary and translator with the embassies in Jerusalem, Janina, and Beirut.

Oleksandr and Katerina Rostkovsky spent their holidays in their home land, as evidenced by autographs left in the well-known Kachanivka Album owned by the Tarnovsky family, one of landlords, philanthropists, and art collectors. The album boasts a total of 600 autographs left by guests visiting that scenic spot of Ukraine at different times, among them Mikhail Glinka, Nikolai Gogol, Taras Shevchenko, Mykola Kostomarov, Panteleimon Kulish, Marko Vovchok, Ilya Repin, Dmytro Yavornytsky, and others.

In 1893, the diplomat’s family moved to Italy, after Rostkovsky had been appointed Vice Consul to Brindisi. Macedonia was the fateful landmark in his career. At the time it had become a hotbed of the Balkan struggle. The Rostkovskys displayed utmost self-control under the gravest of circumstances. Just as the people on most other consular missions thought it best to isolate themselves from the situation, preferring to act as onlookers, the Russian Consul continued to work actively, all apparent perils notwithstanding. On the morning of August 8, 1903, on his way to the office, Oleksandr Rostkovsky was short by a Turkish guard. On learning this, St. Petersburg demanded the “most complete” satisfaction from the Turkish government. As mentioned above, this implied diplomatic measures as well as a demonstration of force. It took repeated apologies, on the part of the sultan, prince, the ministers, also the promises of a huge ransom and the murderer’s quick execution to prevent Russia’s quick military retaliation.

Details relating to the Ottoman Empire’s compensation were elucidated by The Times, with permission from the Russian Consul’s widow. Katerina Rostkovsky informed that she was visited by Sultan Hilmi Pasha’s official offering her 200,000 francs as a compensation. She asked if the Sultan was offering that money in return for her husband’s blood, saying she and her children would die of starvation, rather than accept Turkish money. Shortly afterward, the sultan offered her 400,000 francs, but the widow adamantly refused.

The family decided to bury Oleksandr in Odesa, and the gunboat Terez was sent there with the coffin onboard. Odesa eyewitness accounts have it that “owing to the clergy, military, and the public, thanks to people representing various agencies and taking an active part in the funeral of Rostkovsky, the ceremony turned out so very impressive, on an extremely large scope, and an exemplary public order was kept, despite the presence of a huge crowd; that funeral was unprecedented in Russia.” Nicholas II appointed an allowance to the widow and children. Katerina Rostkovsky settled at her parental estate in the vicinity of Chernihiv.

Her further destiny is both interesting and dramatic. As an immigrant in Italy, she wrote memoirs titled Princess de KR: The Light, Shadows, and Darkness of Russian Life. A copy is still in one of the Italian archives. KR was eventually deciphered as Katerina Rostkovsky by the Italian Ennis Bordato who wrote the book Under Alien Skies (2000). It is soon to be translated into Russian, as the events described therein, dating from the early twentieth century, still seem quite relevant.