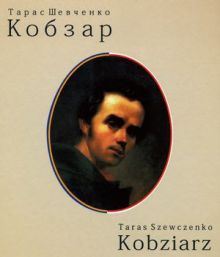

Last week, The Day’s editor-in-chief received a magnificent present, the new edition of Kobzar in two languages. The book was signed by all project participants. And the project was initiated by the Lviv National Agrarian University and the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin.

Polish writers started translating Shevchenko’s works in 1860. For example, the volume printed by the Ukrainian Scientific Institute in 1936 in Warsaw included 107 poems translated by Maria Benkovska, Kostiantyn Dumanski, Yaroslav Ivashkevych, Bohdan Lepky, Kazimierz Wierzynski, Jozef Lobodowski. But it should be noted that Polish readers received an opportunity to appreciate the complete translation of Kobzar thanks to the professor of the Lublin Agricultural Academy Petro Kuprys, who was our fellow countryman, by the way. His translations were the basis of this edition.

The idea of publishing Kobzar in Ukrainian and Polish appeared a few years ago. The publishing committee included famous Ukrainian and Polish scholars: Joseph Kolodziej, Eugeniusz Krasowski (the editor of the book), Jan Glinski, Mykhailo Lesiv, Volodymyr Snitynsky, Stepan Kovalyshyn, Mykola Roshchenko, Albert Novatsky, and Beata Pyc. The implementation of this idea (Kobzar was printed at the Lublin Catholic University Publishing House) is not only a special way to honor Shevchenko’s memory, but also a way to bring his testaments to the present-day life. Among them is a testament to unite with Poles.

The poem To Poles says: “Hold your hand out to the Cossack, come to him with honest heart!” By the way, soon after the poet’s death, the Polish liberation uprising started in 1863. A shield, divided in three parts (Polish Eagle, Pogon Litewska, and Rus’ archangel Michael) was the symbol of the rebellion; it showed the Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Lithuanians’ striving for freedom. Basically, this emblem is a symbol of unification.

The first full edition of Kobzar in Ukrainian and Polish is still hot off the press; it was presented in Lviv last week. Among the presentation guests were Eugeniusz Krasowski, Consul General of Poland in Lviv Jaroslaw Drozd, first deputy head of the Lviv Oblast State Administration Bohdan Matolych, professors at the Ivan Franko Lviv National University Oleksandra Serbenska, Vasyl Lyzanchuk, and Alla Kravchuk, assistant art director at the Maria Zankovetska National Academic Drama Theater Yurii Chekov, writer and public figure Roman Lubkivsky. It is obvious that this book will become an important phenomenon in the cultural life of both nations.

COMMENTARY

Roman LUBKIVSKY, poet and public figure, laureate of the Taras Shevchenko National Prize:

“The bicentennial of the author of Kobzar, this holy book of the Ukrainian nation, promises new monuments in the countries where Shevchenko’s word has come to be perceived as their own, and where the Ukrainian community is consolidated and active. And yet it is the translation and re-printing of his works, translated by either groups or talented individuals, devoted to the Kobzar’s muse, that will play the key role in bringing Shevchenko closer.

“The complete edition of Kobzar in Ukrainian and Polish (Lviv-Lublin, 2012) testifies to such a tendency.

“Speaking at the presentation of this wonderful edition I said that relations between neighboring nations can often be ‘decoded’ by prominent individuals. Thus, Taras Shevchenko and Juliusz Slowacki have perhaps done (and are still doing) the most for defining the complex Ukrainian-Polish relations. The genii of the two nations, almost contemporaries, political exiles, whose tracks crossed in Kremenets and Vilnius and whose work overlapped in Haidamaky and The Silver Dream of Salomea, were able to considerably reduce and neutralize the conflict-laden, painful themes (this issue is convincingly expounded in Ivan Dziuba’s detailed paper Slowacki and Shevchenko). Do Polish and Ukrainian elites owe their huge experience of rising above political confrontation, national resentments, all sorts of strife and misinterpretations to these two men?

“In the Polish-Ukrainian continuum everything matters: biographical plots (e.g., Shevchenko’s friendship with repressed Poles in exile and his admiration for Mickiewicz), his influence on “Ukrainian school” in Polish literature, and most importantly, his liberation, state-building visions.

“As for translating Shevchenko into Polish, this issue is expounded in detail by a renowned Lublin-based Ukrainian linguist Mykhailo Lesiv in his foreword Poezia Tarasa Shevchenka u perekladi Petra Kuprysia (Taras Shevchenko’s Poetry in Petro Kuprys’ Translation). He adduces the names of prominent translators of various generations starting from 1860: Wladyslaw Syrokomla, Jozef Wlodzimierz Slobodnik, Kazimierz Andrzej Jaworski, Jerzy Plesniarowicz, and Bogdan Drozdowski. Lesiv also gives Ukrainian translations their due: the classic of Ukrainian literature Bohdan Lepky, the “Young Muse” poet Sydir Tverdokhlib, and the literary critic and publisher Pavlo Zaitsev also contributed considerably to translating Shevchenko into the Polish language.

“Of course, not every translation has stood the test of time. We can expect that someday a new interpretation of Kobzar will be necessary. But what the Volhynian translator Petro Kuprys did, and how his work was appreciated by the Polish compilers and publishers, as well as two universities (the Catholic University in Lublin and the Agrarian University in Lviv), shows the unlimited potentiality of fruitful cooperation in the sphere of humanities. The presented edition is a reprint of the first publication of several years ago, which was highly appreciated in Poland and Ukraine.

“Now, a few words about the presentation proper. It was a true festival of intellectuals, with a warm, cordial atmosphere. Of course, the account offered to The Day was purely informative. The picture can be complemented by two facts: the recent unveiling of a monument to Slowacki in our capital, and the recent publication of his works in two volumes by Svit Publishers.”