At first we met with Leonid Hrabovsky, who lives in New York, at the launch of Ivan Dziuba’s book On three continents. During our conversation we mentioned the numerous scores of the composer that are preserved at the Central State Archive Museum of Literature and Art of Ukraine (TsDAMLM) in the Fund of the Dovzhenko Film Studio. Hrabovsky looked at his own music manuscripts in the reading hall of the museum, and after the offer of the director of TsDAMLM Olena Kulchii he agreed to bring his private archive from the US to Ukraine. Later we contacted him on the Internet.

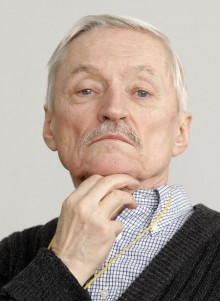

Leonid Hrabovsky is an actual academician of the Academy of Art of Ukraine, a recognized classic, “brain center” of Kyiv avant-garde. However, he for the first time told The Day about some important cornerstones of his biography without hiding the details. His contemplations about the current political situation, oeuvre of Ukrainian composers of the previous centuries, the situation on the world art market are worth of no less attention.

“SPIRIT OF MUNICH OF 1938 HAS OVERWHELMED PRESENT-DAY EUROPE”

Mr. Hrabovsky, last time you visited Ukraine during the first weeks of Maidan. What was your first reaction?

“Although at that moment I was in Kyiv, because my author’s concert in the Archive Museum of Literature and Art was prepared, this event came unnoticed to me. Only after December 9, when I came back to America, I found out about everything in detail on the Internet. Since that day it has been taking me several hours a day to follow the news on Maidan and later the war with Russia. Till mid-July all my work was practically paralyzed because I was worried about these events. Only by my will I have managed to put an end to my prostration. My first reaction was horror, my heart sank, since then I have felt constant increasing anxiety. But for a long time I have felt subconsciously that this tension and abnormal situation, the withstanding which has increased deeply in Ukrainian society over the past 10 years had to finally give way to some bloodshed.”

You must have been following what happened to Crimea and now goes on in the Donbas. In your opinion, under what conditions could we have avoided this?

“This is the result of the fact that in our country, unlike in Poland, the Czechoslovakia, and Germany, lustration has not been held, the Communist Party has not been banned forever, and KGB has not been announced a criminal organization; no regular commission on investigating into the anti-Ukrainian activity in the Verkhovna Rada has been created. This feebleness, naivety, and tenderness, our national qualities, have enabled the enemies of Ukraine to quickly penetrate into all the power structures with their agents, bribe the amoral moneymakers, and practically paralyze the possibility of momentary resistance to any anti-Ukrainian actions. This is the reason of our current defeats.”

As for the current situation, what can the people of art do?

“It is hard to answer this question. Although Dostoevsky asserted that beauty would save the world, history proves that beauty has not saved anything, and its deeds are helplessly drowning in the oceans of moral dirt, cheapness, aggressive vulgarity of the mass culture. Let’s take for example the beginning of the World War I: the pacifist movement launched by such personalities as Anatole France, Romain Rolland, and others, in spite of all of its efforts and calls, was unable to stop the war, and it ended only when the forces of the belligerents started to exhaust. I think nothing is left for us the artists except for doing what we do silently and stoically, and giving no support to the enemies of Ukraine. We must clearly understand every step we take, ignore their cultural space. At least as long as the totalitarian chauvinistic insanity in this space remains. And it will remain for a long time.”

Do you have a vision of how everything may end for Ukraine?

“The best thing would be if Ukraine was accepted to NATO without hesitation, or was made an important ally and given the most up-to-date armament. But such scenario is not unfolding, because the spirit of Munich of 1938 has firmly overwhelmed present-day Europe, which is egoistic, hypocritical, and partially bribed. It will bitterly regret, but it will be too late. I think the worst and most realistic scenario is a long-time hybrid war aimed to exhaust the country – for 5 or even 10 years. Three-minute-long applause to Poroshenko in America is applause of the audience to a courageous gladiator who fights well and an encouragement for him to go on, while they will be watching, because it is exciting and interesting.”

Can you recall the turning moments of your life?

“During the first years of conservatoire I was an absolute neophyte in modern art. Whereas Picasso’s works were brought to Moscow in the end of the 1950s, it was unthinkable in Kyiv. I was familiarized with modern art by artist Vilen Barsky, who lived nearby. He was living in Bessarabska Square, while me – in Leo Tolstoy Square. And at least three times a week he came to my place to listen to recordings I had. He brought me Polish magazines which published the reproductions of Picasso, Dali, Klee, and Kandinsky. One day Barsky brought me an issue of Polish magazine Poetry, which published the translations of fragments of Saint-John Perse’s Amers, which soon became the source for composing my melodrama, Sea. During the third year of conservatoire I got acquainted with Ihor Blazhkov. It happened at a Western music history lecture delivered by Ada Herman (since that time I remember her crown words: ‘All symphony works by Liszt are part of the program.’). Blazhkov had a score of the First Symphony by Shostakovich. He was holding it proudly, showed me the first pages. In fact at that time I didn’t know or understand the music by Shostakovich or Prokofiev. I started to understand it approximately in 1957-58. At that time Shostakovich won the Lenin Prize and the score of his Seventh Symphony was printed, which had not been published since the war time as a modernist and formalist work. Actually, this was one of the turning points for me. Another one was the appearance in 1957 of the first long-playing records. They were sold in Passage. Later Blazhkov started to receive from the West many records of the music of the 20th century, and for all of us it became the main source of further self-education and broadening of horizons. In 1960 I translated the book received by Blazhkov, Introduction to the technique of composition with 12 tones by Hanns Jelinek, which were further studied by Sylvestrov, Hodziatsky, and me.

“In 1958 the Philadelphia Orchestra, and in 1960 New York Philharmonic Orchestra came to Kyiv. In the concerts of the latter we heard The Rite of Spring by Stravinsky etc.”

“THE PERSON WHO DOES NOT RETURN”

How did you find yourself in the US?

“I’ve been living in America since August 7, 1990. I came to New York. From there I was sent to Boston where I for 1.5 months lived at Hryhorii Hrabovych’s place. And since October I have been living in New York. I belong to people who don’t return. I came to America on a business trip from the Union of Composers of the USSR to deliver several lectures. But Virko Balei and I knew that I was leaving forever. There were many reasons. The first and foremost one is an absolute lack of prospect of living in Moscow, where I didn’t have an apartment of my own. At first I wanted to go to Poland with its Warsaw Autumn and other festivals of modern music. In 1979 Andrzej Nikodemowicz emigrated to Poland from Lviv. He said there was a chance for me to teach in Lublin together with him. But the migration could be arranged only with the help of a simulated marriage with a Pole. I tried to find such candidates, but they either disappeared, or refused. Then I understood that I was in the trap of our ‘Office of Deep Drilling’ and they won’t let me go to Poland. In 1981 I moved to Moscow, perestroika started soon after that, and in 1987 they began to let people out of the country. Then I for the first time (at invitation of Virko Balei) went to Las Vegas to a festival where four of my works were performed. This was an official business trip and a trial journey. Then the magazine Soviet music where I worked sent me to Vienna to interview Stockhausen, which was dedicated to the anniversary of Beethoven. Later I went to an elite symposium festival to Sandomierz (Poland), where I delivered a small report on my creative work and demonstrated a couple of recordings. When I understood that I was quite able to travel around the world, I decided to use this opportunity.”

Besides, you dreamed about electronic music.

“In fact, those were platonic dreams. At the beginning of the 1970s owing to requests of different people, the head of the Council of Ministers of the USSR Kosygin signed the order on purchasing an English sequencer for 25,000 gold rubles. It was placed in Oleksandr Skriabin Museum. On the basis of the museum a Studio of Electronic Music was organized, where Murzin’s sequencer was made a part of it (Yevhen Murzin invented a kind of graphic synthesizer; I suppose that the Xenakis synthesizer repeats his idea or even is a copy of Murzin’s invention). Only five composers were allowed to work at the studio unofficially: Eduard Artemiev, Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Edison Denisov, and I think Vyacheslav Artyomov. Every time I came to Moscow I was told that they lacked an assistant on technical questions. Finally in 1979 the Dovzhenko Film Studio invited me to write music to the film Red Field and I decided to make in Moscow several electronic fragments for the film. I managed to create three fragments, but they were not included in the film. I don’t know where they are and whether it is possible to find and restore them.

“Soon after Tikhon Khrennikov, who was Alfred Schnittke’s enemy on all fronts, achieved the dissolution of the Studio of Electronic Music, and the sequencer was sold for kopeks to the Moscow University, to the cabinet of phonetics.”

ON LIFE IN THE U.S.

Who represents Ukrainian music in New York and how?

“There is no one to take care of this in New York. There used to be the Ukrainian Music Society, but people who founded it were thinking in a too provincial manner. Currently none of them is alive and the society passed away together with them. Something new will probably emerge. By the way, Hryhorii Hrabovych told me that a musicology section is organized in the Shevchenko Scientific Society (it used to be there, but later it disappeared), and asked me to take part in its work. He also said that some concerts are planned.”

Are you a free artist in the US or do you have a regular job?

“For over 13 years I have worked as a classical music consultant in a music recordings shop, until it was closed. Over this time I earned a small American pension. Besides, as a retired person I pay only 30 percent of rent for my dwelling, the rest is reimbursed by the state.”

Does the work of a composer bring any income? Do they return you the honoraria from performing your works?

“You can forget about that. For example, the ensemble Continuum (in the 1990s it came to Ukraine several times) performs many works by Ukrainian composers, such as Sylvestrov, Bibik, Stankovych, Shchetynsky, Kolodub. In particular, my work When based on Khlebnikov’s texts was most broadly spread geographically owing to Continuum. Only in Brazil they performed it in several places. My honorarium was 1.87 dollars. The Sikorski Music Publishers Company in Hamburg, with which I have been in contact since 1995, had done nothing to promote any of my works. My honorarium over these 20 years has made several euros. And only once (in 2007 or 2008) I earned as much as 100 dollars: all of a sudden my forgotten Symphonic Frescoes were performed in Slovenia. But Sikorski does not have anything to do with this.”

You used to compose many works for cinema. Have you succeeded to work with American film studios?

“No, they don’t invite me to the cinema now. But I’m happy that I have made copies of all of my scores written for the Dovzhenko Film Studio (their autographs are stored in the TsDAMLM of Ukraine). I plan to make a computer version, in order to have demonstration material with me. Now there are many small TV companies with small budgets. Apparently, for them a composer who does not need a symphony orchestra to record the music would be a finding.

“So, in January 2012 in Lviv I showed how a film soundtrack created completely on computer may sound. This was a kind of a call for discussion. There can be many opinions in this concern, but I think that a computer can fully substitute a symphony orchestra where it is unreal to find or hire an orchestra.”

ON REVISION OF MUSIC HERITAGE

Archive museum preserves hundreds of personal funds of composers of the 20th century, outstanding masters. For example, one of our gems is the huge archive of Mykhailo Verykivsky whose contribution into the history of Ukrainian music is still to be estimated. Like the contribution of many of his contemporaries.

“I think Verykivsky composed approximately in the same style as genius Mykola Leontovych would have continued to compose, if his life didn’t end so tragically. In his vocal poem Monk based on Taras Shevchenko’s text I feel inspiration, classical line, which is polyphonically perfect and richly decorated, the orchestration is perfect in the canons of romantic style and practical, conceived by opera conductor Verykivsky’s experience. Together with Oleksandr Shchetynsky we have talked much that, for example, Mykola Lysenko’s works cannot be presented to the world in the way they were created. They must be carefully edited, whereas Leontovych does not need any editing. Unfortunately, Lysenko because of his biases or, I would even say, light-heartiness, didn’t understand the advantages offered to him by the invitation of Rimsky-Korsakov to Petersburg to take the position of a conductor. If he didn’t refuse, neither Revutsky nor Liatoshynsky would later have problems with Taras Bulba.

“Two years ago we were at his anniversary soiree in New York. Local Dumka was singing. Many works call to question. Tamara Bulat was still alive then. She organized a conference in New York and for the first time showed the lifetime publications of his vocal works based on acutely political texts by Shevchenko. In some of them Lysenko really reaches almost Mussorgsky’s level. But such works are innumerous, mostly this is solo singing.

“The symphony-cantata by Stanislav Liudkevych Caucasus with its emotional elevation, perspicacity, the power of the national element (especially in the final part), should still be carefully revised: some connections should be added between long parts (as is known, there are many fugues that are written quite skillfully). At that time this work could become a trademark of Ukraine, a historical monument of our life then.”

“MY METHOD OF COMPOSITION NEEDS COMPUTERIZATION”

How does the process of composing music look like? How long do you work on a composition?

“When a person is forced by circumstances to move from one place to another, it takes him many years to implement some of his ideas. Let’s say the idea of vocal work to Skovoroda’s Latin texts has existed since 1971, when its anniversary exhibit took place in the Museum of Ukrainian Art. At that time I stopped on one of his Latin poems, but it was only in 1991 that I managed to accomplish the work. An impetus to this was organization of my author’s concert in New York.

“The 1960s and 1970s were my most productive time. In 1977 I reached a certain limit: I finally understood that my method of composition needs computerization. It was no longer possible for me to continue to work with a pencil and checked paper. This system is in the bud in Homoeomorphies and it was completely formed in Concorsuono for French horn and Concerto Misterioso. Later there was Moscow as a reloading point. Before moving to the US I couldn’t find an English text-book. All text-books and dictionaries in the black market were very expensive, because everyone was leaving for America or Israel. And those who were going to Israel after all found themselves in the US. What could I start in the US without any knowledge of English? It took me three years to learn to talk and think in English, because I was far from being young when I emigrated.”