The Byzantine heritage is an integral part of present-day European identity. Its “traces” are invisibly present in various spheres of our life – from the household milieu to politics, fashion, and high art. At the same time, perhaps no other period of European history appears in our consciousness in such a contradictory and illusory image as the Byzantine Empire does. The book Return to Tsarhorod, published past year under the general editorship of the Den/The Day’s editor-in-chief Larysa Ivshyna, is an attempt to fill the “personal void of ignorance” and to shed light on, among other things, historical, political, and cultural ties with the Byzantine Empire.

However, although the publication of this book was a conclusion of sorts, this in no way means that the “Byzantine subject” is exhausted. For this reason, we offer our readers an interview with Andrii DOMANOVSKYI, a leading Ukrainian Byzantinist, Candidate of Sciences (History), Associate Professor at the Vasyl Karazin Kharkiv National University.

“ENLIGHTENMENT-ERA STEREOTYPES”

Mr. Domanovskyi, the Byzantine heritage, “Byzantinism,” is often used in a negative light in the context of, for example, corruption or arbitrary rule. To what extent can this be justified? Can you see any Byzantine “traces” in the sociopolitical realities of present-day Ukraine?

Mr. Domanovskyi, the Byzantine heritage, “Byzantinism,” is often used in a negative light in the context of, for example, corruption or arbitrary rule. To what extent can this be justified? Can you see any Byzantine “traces” in the sociopolitical realities of present-day Ukraine?

“We should distinguish between the Byzantine Empire which we regard as a result of the ideological influence of the French Enlightenment, above all in the 18th century, and the real empire. The stereotypes you mentioned emerged in the era of the Enlightenment and, to a lesser extent, of the Renaissance. French enlighteners used the Byzantine Empire’s image to discredit French absolutism. Of course, they could not afford to defame the monarch, but they could do so with respect to his likings and ‘playthings.’ The Byzantine Empire was very close to French kings from the Louis XIV times in terms of style and, to some extent, ideology. Since then, the image of ‘Byzantinism’ has been occupying a prominent place in European culture. Maybe, the one who mostly contributed to this was not so much Voltaire, Rousseau, or Diderot as a British historian, Edward Gibbon, who wrote the multivolume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, in fact a work on the Byzantine Empire’s history. This created a stereotype that eventually found itself in our culture, too. Even Taras Shevchenko was under this influence to a certain extent – some interesting studies on how he perceived the Byzantine Empire were recently published [read below. – Ed.].

“A stereotypic vision of the Byzantine Empire was established after the Enlightenment and was used in the 19th century and later to mark all kinds of negative phenomena. A similar story awaited the Middle Ages which are associated, above all, with the plague, cultural and economic degradation. Another illustrative example of historical stereotypes is the Society of Jesus.

“In my view, the Byzantine Empire suffered unjustifiably to a large extent, even though such things as corruption, venality, servility, etc., were really spread there as, or even more, widely as in the then Western Europe. These were perhaps more conspicuous in the empire owing to societal differences. For the West cultivated the chivalrous ideal, the ethics of honor, and feudal hierarchy. For a feudal lord and a knight, honor and property were more important than life – he was ready to die on the battlefield but not to surrender. Conversely, Byzantines were ‘more flexible’: they could make concessions and violate an oath. They were diplomats and merchants, and they were much more educated than Europeans, especially in the early Middle Ages (before the 10th century). Where barbaric kingdoms wielded the sword, Byzantines could ‘shed ink instead of blood.’ Counteragents interpreted this tactic as slyness and perfidy, although in reality it was nothing but diplomacy, when they simultaneously played on many chessboards, – it was soft power, to use a modern term.

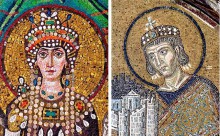

THE BYZANTINE HERITAGE “TRACES” ARE INVISIBLY PRESENT IN VARIOUS SPHERES OF OUR LIFE – FROM THE HOUSEHOLD MILIEU TO POLITICS, FASHION, AND HIGH ART. PICTURED LEFT: EMPRESS THEODORA, A MOSAIC IN THE BASILICA OF SAN VITALE (RAVENNA, ITALY). PICTURED RIGHT: JEWELRY FROM THE DOLCE & GABBANA COLLECTION / Photo from the website ARCHAE.RU

“But it is difficult to say if there really is a genetic bond between the Byzantine Empire and the Eastern Christian, Orthodox, and Slavic world. To trace it in the context of social mechanisms and world-view stereotypes, one must do thorough research. In all probability, there was no direct impact here either in the Kyivan Rus’ era or later, for it is not so easy to transfer the cultural code from one society to another.”

“A HOSTAGE TO RUSSIAN IDENTITY”

Ukraine and Russia are arguing, indirectly and sometimes directly, about the right to the Byzantine heritage. Incidentally, this subject became the object of an acrimonious debate in Moscow again shortly after the Den’s Library book Return to Tsarhorod has been published. Russia is a country that permanently suffers from the crisis of identity. Suffice it to recall that they consider themselves descendents of Kyivan Rus’ and the Golden Horde at the same time. And to what extent justified are their claims to the Byzantine heritage? Can you see any differences in the way Ukraine and Russia receive Byzantine culture?

“It is a difficult question. I must say first of all that Russia has seen a powerful revival of Byzantine studies in the past 25 years. To tell the truth, this discipline was quite well developed in the Soviet era – especially socioeconomic research. Now we can see the subjects that used to be secondary and sometimes even censored. For example, the history of Byzantine church, theology, philosophy, art, etc., is flourishing now.

“These trends have coincided in time with the need in certain ideas that would single out Russian post-Soviet identity. For, while Ukraine traditionally builds its identity on ethnic principles, Russia has never tolerated an ethnic discourse. Let us not forget, either, that it is a multiethnic state with various subjects of a federation. They have always been seeking some other answer to the question of what it means to be Russian. And the Byzantine subject has ‘hit the bull’s eye’ in this case.

“I can remember what a stir, a real explosion, the political film The Fall of an Empire: The Lesson of Byzantium [2008, directed by Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). – Ed.] caused. It turned out that this premiere was much more important to Russian society than films on Kyivan Rus’ or the Romanovs (although this kind of movies, sometime of rather a high quality, have been made before). It was praised and criticized – experts took diametrically opposite stands in assessing it. It was, of course, an ideological, overtly state-sponsored film – it was released at the end of Putin’s second presidential term shortly before the elections, when a debate raged about his successor. Speaking of Byzantine realities, the film’s authors must have meant Russia. What is an imperial identity that combines different ethnicities, languages, and cultures? What does it mean to be an empire-builder, a ‘Roman’? A state-oriented discourse is needed. These were the key themes of this picture. Russian society seems to have really recognized itself. Even such negative aspects as corruption, the complexity and entanglement of the state mechanism, and interdepartmental rivalry looked very familiar to audiences. The cultural heritage, the icon-painting tradition, the Byzantine world-view, and church embroidery – all this was secondary to Russians. Instead, they recognized themselves through the idea of imperial statehood. It is very telling.

“In 1991, a few days before the abortive coup, Moscow hosted a major international congress of Byzantine studies. It is held once in five years in various countries. A small group of the leading Byzantinists was invited to meet the then USSR vice-president Gennady Yanayev who spearheaded the putsch some time later. There was also among them Ihor Shevchenko, a Ukrainian-born US academic. They soon began to talk about the Byzantine heritage. Shevchenko was surprised very much, when Yanayev asked if the Byzantine Empire had been a totalitarian state. Later he wrote an interesting article of the same name on this matter. He particularly pondered in it over why that man was interested not in the Byzantine Empire’s spirituality, culture, or art heritage (which Western Europe focused on) but in, above all, the idea of state formation and whether the Russian Empire and the USSR were its embodiments.

“The Byzantine Empire became one of the foundations of modern Russian identity and, at the same time, its hostage. For the Russians have nothing else – only the cult of victory in World War Two, or, in the dimension of the official Russian ideology, the Great Patriotic War, and this bizarre imperial concept. They cannot fully endorse the Golden Horde idea due to differences in terms of religion and traditional culture.

“But in Ukraine the reception of the Byzantine Empire was rather difficult and depended on several key moments. In the 19th century, when Ukraine saw a great national renaissance and Ukrainian identity was in the making, the Byzantine Empire became topical again. The most illustrative example is perhaps Taras Shevchenko. What prompted the poet to receive the Byzantine Empire was, first of all, the books he read. In particular, Shevchenko knew the works of French enlighteners. Secondly, the Russian Empire began to take a rosy view of the Byzantine Empire. Watching this, Shevchenko writes, accordingly, about the Byzantine Empire in the negative light, as if it were something imperial and ‘pro-Russian.’ This is really a key moment. Identifying the Byzantine Empire with Russia, an antidemocratic and anti-Ukrainian empire, has been part of the Ukrainian intellectual tradition since then. We can see some instances of this vision even today, particularly in the speeches of some modern-day intellectuals, such as Oxana Pachlovska. In my view, the fact that Ukraine continues, to a large extent, to look at the Byzantine Empire with the eyes of Russian imperial discourse, is a big minus. Another important source of Shevchenko’s perception of the Byzantine Empire is Cossack historiography. His poems clearly show identification of the Byzantine Empire with… the Ottoman Empire, i.e., Turkey. For Shevchenko, Turkey is an ‘Islamic enemy,’ a Big Alien to whom the Ukrainian nation is counterbalanced:

Byzantium is full of ire.

It seeks to grip the shore of fire,

But screams and rises up and dies

As sharp blades silence all her cries.

(from the poem Hamalia,

translated by С.H. Andrusyshen

and Watson Kirkconnell)

“So the Byzantine Empire was perceived in Ukraine through alien, Russia-imposed, optics by contrast with a number of other Orthodox countries, particularly Bulgaria and Serbia, which had set up strong Byzantine schools and managed to work out their own profound and original perception of the Byzantine heritage because, for them, the Byzantine Empire is at the same time an enemy and the main source of cultural traditions.

“The destiny of Byzantinism in the Russian Empire is quite particular. There were university centers – above all, St. Petersburg. The academics who worked in Ukraine then, for example, Fyodor Uspensky at New Russia University in Odesa, moved to the imperial capitals or Constantinople. Local schools remained provincial and looked at everything through the eyes of Petersburg. Later, when Uspensky died in 1928, Byzantine studies were cut short in the USSR. A gradual revival began as late as 1940 during the war. But this only occurred in Moscow, Leningrad, and, oddly enough, in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg), where, thanks to the efforts of talented academic Mikhail Siuziumov, a local school was established.

“In Ukraine, even though pre-revolutionary universities of Odesa, Kyiv, and Kharkiv had their Byzantinists, after the early 1930s crackdown they were never restored. In this respect I agree with Yaroslav Hrytsak who believes that in Soviet Union historical science in Ukraine boiled down to the history of Ukraine, while researches into world history were prerogative of the imperial center, even the aspects that concerned us directly. As for Byzantine studies, the only exception worth mentioning might be Petro Karyshkovsky (1921-88) from Odessa University, although he also fell under the influence of the general imperial discourse.”

“UKRAINE IS A ‘BLANK SPOT’ TO THE WORLD BYZANTINE STUDIES”

Where is Byzantinism being studied in Ukraine these days?

“At a Byzantinists congress held in late August in Belgrade, Ukraine was represented by Kharkiv and Lviv researchers. Moreover, there are Byzantinists in Kyiv, Chernivtsi, and Odesa. I mean independent scholars engaged in quite diverse fields. Although we have the Ukrainian National Byzantinists Committee, there is no real coordination between these researchers. In countries like Bulgaria, Serbia, Russia, or Poland, this issue is at a different level. They send numerous delegations to the congress, and hold preliminary sessions. Ukraine sent only five participants. I have to admit that Ukraine is a ‘blank spot’ to the world Byzantine studies and, unfortunately, we are still as often as not regarded as part of Russia, especially if the works of our researchers are prepared in Russian.”

In addition to scholarly researches, you are also popularizing Byzantinism among the wide audience, in particular, you created a website “Basileus. Ukrainian Byzantine studies.” It is pleasure to note that the republished materials sometimes include articles of our newspaper. What made you start this project?

“The website was made about 10 years ago and first it worked on the platform of Kovalsky Eastern Institute of Ukrainian Studies, where I collected information on Byzantinism primarily for myself. Then, having analyzed the visiting statistics, I realized that I was not the only one interested. Now the site is operating on the Wordpress platform. It contains information on publications, conferences, theses defenses. Incidentally, in the theses chapter one can find a few dozens of works defended within the independence years. The overwhelming majority of works, if not all, meet international standards. There is a row of truly outstanding researches, their authors can definitely be named top scholars.

“Besides, the site contains such popular-science materials as texts, videos, opinion polls concerning attitude to the Byzantine legacy, etc. By the way, such polls have always aroused interest. I think later they can become subject of scholarly researches. It is very pleasing that Den also approaches the Byzantium theme.

“Recently, an idea has emerged to use the website to stimulate the activity of the Ukrainian National Byzantinists Committee and set up the Ukrainian Association of Byzantine Studies – it is being registered right now. In this way we hope to enhance coordination among the researchers, organize all-Ukrainian Byzantinists conferences, as well as attract extra funds.”

ON THE STRENGTH OF THE OPEN SOCIETY

What other aspects of Bysantinism influence on Ukraine (that may go unnoticed to a man in the street) can we discuss today?

“A great many things common to us nowadays originated in Byzantium – from a fork to a hospital as a social institute.

“I like to draw parallels between Byzantium and political activity of soccer fans in Ukraine. During the Maidan and war, we saw people who had always been rivals and even enemies on and outside the stadium unite by common values. It reminded me of relations between the competition supporters on the Byzantine hippodrome. There were two leading parties, two associations called ‘demes,’ or ‘factions,’ the Blues and the Greens, according to the colors of charioteers’ uniforms. Two more parties, the Reds and the Whites, were less important and depended on the stronger ones. There was constant rivalry between them, and when the state suffered turbulence and riots, different parties united to fight for their right and social justice.

THE BOOK RETURN TO TSARHOROD, PUBLISHED PAST YEAR UNDER THE GENERAL EDITORSHIP OF THE DEN/THE DAY’S EDITOR-IN-CHIEF LARYSA IVSHYNA, IS AN ATTEMPT TO FILL THE “PERSONAL VOID OF IGNORANCE” AND TO SHED LIGHT ON, AMONG OTHER THINGS, HISTORICAL, POLITICAL, AND CULTURAL TIES WITH THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE / Photo by Artem SLIPACHUK, The Day

“At classes with my students, I drew similar parallels and also compared Ukraine and Russia in this context. In my opinion, the Byzantine legacy in Ukraine is correlated to the early, Late-Antique Byzantium of the 4th-7th centuries. It is about an open, politically active society, where, in particular, a few religious movements compete. While Christianity wins, paganism remains for a long time. Later, after the 7th-8th centuries, Byzantium degenerates and under influence of various factors becomes a closed society focused on itself and its survival. It divides into small groups and gives the state power all the functions of protection, administration, regulation of life, etc. A new specific form of social contract comes forth.

“Russian liberal publicists often repeat that in their country they had a kind of contract of distinguishing between the state and private lives – it’s like we mind our own business until the state leaves us be. Then, during his third (in fact, fourth) term of office, President Putin has allegedly infringed this contract. Something of the kind happened in Byzantium – the state usurped the entire system of the society control, and people only lived their private lives. To my mind, it is the reason why, together with other political and economic reasons, Byzantium ended in destruction.

“Another example visualizing changes that happened to the Byzantine society is a reaction to foreign aggression. During the Arab conquests, the Late-Antique empire (the Middle-Age Byzantium was just being born at the time) lost a significant part of its territory, but simultaneously, the nationwide resistance wave rose up, and due to that sort of people’s militia the attackers were finally defeated. People rose against the attack of another world, another religion, defended their capital twice, and started to regain their lands. And in half a millennium, in 1204, when crusaders came, no one would even lift a finger – people did not rise to defend their country against the ‘strange’ West, Constantinople was severely looted. The Byzantines did not offer mass resistance to the Turks either, who came in the 13th-15th centuries. Among the Turkish invaders there were also Orthodox Christians, former Romans…

“Now let us think, is anything like Ukrainian volunteer movement possible in present-day Russia? I mean nationwide resistance to the aggressor on non-state basis. Nowadays Russia has a strong enough state apparatus but a weak society. In Ukraine – vice versa. In this context the Byzantine history is an educational example.”

“BYZANTIUM AFTER BYZANTIUM”

Can we say that in the 15th century, after the fall of Constantinople and its turning to Istanbul, after the Ottoman Empire emerged in this area, the Byzantine civilization stopped existing?

“In no way! Today the Byzantine civilization is as well alive – in a cultural code. It is preserved in the Greek society, in the Phanariot culture [descendants of Greek aristocracy that remained in Constantinople after the city was captured by Turks. – Ed.], in societies of peoples conquered by the Ottomans. This continuity definitely exists on the mental and mundane level. That is why one of the directions in modern Byzantine studies can be characterized as studying ‘Byzantium after Byzantium’ (according to terminology of a Romanian historian Nicolae Iorga).

“In contemporary culture, Byzantium frequently turns up in absolutely unexpected ways. For example, in 2012, a movie called Byzantium was released, it is about... vampires. In 2012-14 collections of leading Western fashion designers (Dolce and Gabbana, Karl Lagerfeld) we can trace Byzantine motifs. They contain Byzantine glamour, allusions to Byzantine art, icon painting, mosaics – very vivid works.

“Quite a few works related to the Byzantine theme are integral part of the Western culture. First comes to mind William Butler Yeats, the Irish poet, Nobel Prize winner, with two of his poems translated to nearly all languages, ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ and ‘Byzantium.’ To me, they read about Byzantium as a symbol of perceiving the Different, the Strange. While in ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ it is shaped as a perfect land of eternal youth (‘Caught in that sensual music all neglect / Monuments of unageing intellect’) that lives in harmony with the Universe, ‘Byzantium’ goes about the kingdom of sin, gore, and greed. Such accents in Western culture are fairly numerous.

“I remember a past-year article in a foremost French newspaper, Liberation (issue of May 12, 2015) that was about a school reform resulting in deleting a chapter dedicated to Byzantium from the program. The article’s authors are outraged – why they found time to study Arabian world and no time for Byzantium. Citing historian Fernand Braudel, they write about Byzantium as a civilization that originated images determinative to the European identity, implemented visualization and made symbolic depiction prevail over text. We can find it in Byzantine mosaics, church apparels, icon painting. This very visual culture later gave birth to Renaissance and Italian school. As the article authors state, icons in a smartphone are also traces of Byzantine culture.”

(To be continued)