For Wanda

Rock singer Sixto Diaz Rodriguez, or simply Rodriguez, shot himself right in front of an unfriendly audience after a failed performance.

More likely, he doused himself with gasoline and set himself on fire while standing at the mic.

Or most likely, he died of a drug overdose.

An untimely death befits a protagonist. A rock star is always falling. A musician dies on stage, even if he actually suffered a heart attack like Jim Morrison, hanged himself like Ian Curtis, or was shot dead like John Lennon. The main thing is to disappear suddenly and before the early 1980s.

Therefore, for example, Bob Marley, who died of cancer in 1981, has not entered the classic martyrology. This cult is not one of death, but rather of proper exit: it is necessary to finish the song, to leave the stage on time (Sid Barrett, for example, did just that, becoming perhaps even a greater legend in his lifetime than the Pink Floyd which was founded by him). Those who fail to do so turn into exhibits in the dimly lit hall of past fame.

Another lot is that of an unrecognized genius who, due to various circumstances, remained known only to a few fans; their missing tapes, unpublished masterpieces, and albums which weren’t noticed in time but gave birth to entire musical styles decades later testify to a deafening loss.

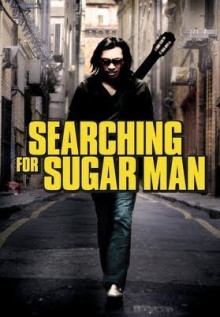

A latent but persistent cult of silence unites these different life schemes. The ringing silence of losses and omissions forms the universe of rock ’n’ roll, filling the light years between the constellations. Malik Bendjelloul, who directed the non-fiction biopic Searching for Sugar Man which deals with Rodriguez, tries to present this dark “matter” in a simple structure.

The Swedish director chose a linear narrative, introduced more and more storytellers, offered diligently made panoramas of the cities they mention, and did not forget about off-screen music. Rodriguez, a hard worker born to a mixed Indian-Mexican family, lived in the half-ruined and depressive city of Detroit.

He composed measured ballads with thought-out lyrics, sang in pubs for his friends.

He showed promise, could possibly rival Bob Dylan himself, was noticed by record companies and critics, but his albums Cold Fact (1970) and Coming From Reality (1971) flopped, selling just six copies. According to rumors, he committed suicide after an unsuccessful concert. One copy was smuggled into South Africa, and Rodriguez became an icon of the anti-apartheid movement there. At the same time, he was utterly forgotten in the States. There was no full name, no place of residence, no relatives; only one photograph survived on an album which few people listened to: it showed Rodriguez in huge black glasses. That was all.

Bendjelloul formalized this factual shortage of information into a documentary detective, and, taking as a starting point the ignorance of Rodriguez’s South American fans Stephen “Sugar” Segerman and Craig Bartholomew, surrendered screen time to them. This is how mythology gets sublimated into myth-making. Moreover, everything that happened to Rodriguez is full of dramatic contradictions: he played music and sang in one place, and became famous on the opposite side of the globe; he was not a rebel, but was perceived as an underminer of the foundations. The most experienced producers fail to explain the reasons for his failure forty years ago. Clarence Avant, the former head of Motown Records label that discovered Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross and Michael Jackson, only shakes his head in rue. Moreover, being “not enough black and not enough white” according to one commentator, Rodriguez was successful with Caucasian youths of South Africa from that generation of Afrikaners who fought against apartheid side-by-side with blacks. South African censors scratched out with nails individual seditious tracks in his albums – the lady who was in charge of censorship under the old regime shows vinyl records with these terrible sinusoidal scars. His very life, real or fictional, is thinned to a stereotypically heroic rock biography.

Can such a person, who has completely merged with the myth about himself, even be real? The director emphasizes this disembodiment in animated openings, drawing a slowly walking figure in a long black raincoat and a wide-brimmed black hat into the Detroit landscape. That elusive guitar-wielding wanderer really becomes the Sugar Man of his most famous song who carries on magic silver ships jumpers, coke, and sweet Mary Jane (the latter is a slang euphemism for marijuana).

Searching for Sugar Man moves closer to the rockumentary genre, the investigation moves from comparing facts to playing with words and music, with geography and history, to that enchanting ambiguity of artful fiction which makes unimportant even the search for solution to the riddle proposed at the beginning.

However, the games end exactly in the middle of the film, since the real (although what does “real” even mean?) Rodriguez is finally found. Here he is, with his three dissimilar daughters, social activism, a diploma in philosophy and an attempt to run for the city council; alas, the silver ships remain over the horizon. Freely composing a legend, the director stumbles where it is necessary to tell about a person, and his optics freeze missing the details of the character.

Bendjelloul dresses Rodriguez in the same raincoat and hat and sends him walking in snowy Detroit. This journey ends where it began, having played the role of a purely ornamental insertion, a rhyme to the animated scene already seen; but we need dissonances, not rhymes – after all, it is the dissonant wind instruments that make the song Sugar Man unforgettable.

The flesh of the fact turns out to be less malleable than the exotic skeleton of myth. A chronicle of a triumphant tour of South Africa in 1998, a hurried stream of good news – Sugar Man has been replaced by Cinderella. Still, a truly accurate moment comes when the character sits by the stove and looks at the fire, saying nothing and commenting on nothing. These seconds reflect Rodriguez’s Indian equanimity and his stoicism, unquestionably present in everything that he did or refused to do. Such a person could, having released two outstanding albums, return to work at a construction site; he could, having tasted the well-deserved fame, give away all the money to friends and return to semi-oblivion and routine/ruin of Detroit.

Being totally indifferent to worldly riches throughout his life and inclined to underground existence, he has always lived on the opposite side of trivial success in the world of show business. Bendjelloul did not discover Sugar Man’s America, but found Rodriguez instead, the greatest antipode in the history of rock music.

***

Searching for Sugar Man

Written and directed by Malik Bendjelloul

Cinematograph by Camilla Skagerström

Music by Rodriguez

Red Box Films, Passion Pictures, Canfield Pictures

Sweden – UK – Finland

2012

By Dmytro Desiateryk