I visited the United States for the second time in April 2006. Whereas in 2003 I had to spend weeks attending a conference and listening to papers given by historians, men of letters, and philologists without leaving the session hall even for an hour, this time my trip had a broader geography, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast. After acquainting myself with the program of the visit, I said I would like to meet Robert Conquest, the noted researcher of the purges in the Soviet Union, author of the substantial work Harvest of Sorrow, and the first Western researcher to recognize the Holodomor in Ukraine as an act of genocide.

Stanford University is a large, scenic campus with its own post office, security service, numerous research foundations, and learned professors, who teach various disciplines to diligent students. Tuition fees range from 43,000 to 54,000 dollars a year, which is a stimulus of sorts. We met with Robert Conquest at the reading hall of the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace. Of British descent, he is a remarkably learned and cultured person whose research and journalist activities are associated with Oxford, where he plans to return in the nearest future.

During our conversation at Stanford, where he is a research fellow, he listened more than he spoke. I asked Professor Conquest how he got around to studying Ukrainian history. He said that in 1937, when he was still a student, he had made a trip to Europe and even visited the Ukrainian pearl, the city of Odesa. The year of the Great Terror would become a matter of special interest for the researcher. During the years of Khrushchev’s Thaw Conquest worked as a journalist, literary critic, and edited a collection of verse The New Line in 1955-1963. He is a noted writer and the author of several works of fiction. He collaborated with Alexander Solzhenitsyn in the 1970s and helped publish English versions of his books. In 2005, his book The Dragons of Expectation came off the presses. Listening to Conquest, I found myself thinking that we know far too little about his scholarly legacy, mostly his well-known monograph about the Holodomor, and that this legacy should be the subject of a dissertation.

Conquest’s student, the noted US researcher James Mace, came to Ukraine in 1990, where he would spend the rest of his life. Mace spoke about his teacher, their joint research project and the work of the U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine. In other words, he familiarized us with the scholarly legacy of a researcher who was well known in the West but taboo in the Soviet Union. In 1968, when Jim was still going to school, Conquest published one of his first papers on Soviet agriculture. That same year his important work The Great Terror appeared in print, followed by reprints in 1971 and 1973.

The two-volume Russian version came off the presses in 1991, the year the USSR collapsed. The book went down in the annals of historiography, although historians’ opinions, especially those of the Soviet generation, were varied. Some criticized it; others admired it, while others continued to debate the issue. The monograph elucidated the causes and consequences of the Great Terror in 1936-1938, yet made no mention of the Holodomor. Judging by the author’s references to S. Pidhainy, V. Hryshko, I. Maistrenko, and K. Kononenko, Prof. Conquest knew about the tragedy of the Ukrainian people.

Who or what prompted Robert Conquest to write a book about the Holodomor? This is a question that occasionally surfaces in the press. In the early 1980s Ukrainian communities in the United States, Canada, and Australia marked the 50 th anniversary of the Holodomor in Ukraine. American political circles showed little interest in the subject. As James Mace later wrote, a generation of English-speaking professional researchers of purely American descent, who had become influential in the Ukrainian community, as well as in the sphere of Soviet studies, proceeded to demand recognition of the Great Famine in Ukraine of 1932-1933.

In June 1981 the Toronto-based newspaper Homin Ukrainy formally announced that Professor Conquest would be writing a work on the Holodomor. He was invited to Harvard University to supervise a research project investigating the famine in the Ukrainian countryside. James Mace, his assistant, was researching the origins of Ukrainian national communism in Soviet Ukraine in 1918-33. Mace recalled later that, while working on his doctorate, he knew all the sources of data available in the West and the historical context of the Holodomor in the Ukrainian SSR and the Soviet Union. The result of their joint research was the book Harvest of Sorrow. The combination of youth and experience, hard facts and political analysis, James Mace’s American Indian energy, and the British scholar’s academic training and knowledge of Soviet affairs proved successful.

I wanted to discuss James Mace and hear Robert Conquest’s opinion. When I asked him about his students, he said quietly: “I’ve never been a traditional university lecturer. I mostly busied myself with research.” He did remember Mace as a gifted Harvard researcher. He knew that his former assistant had died and been buried in Kyiv; he recalled his public appearances at the universities of Toronto and Stanford. Mace’s scholarly biography, especially when he was working on his doctorate at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute and later as a research fellow (1984-1986) is included in the book Day and Eternity of James Mace.

I didn’t dare ask Dr. Conquest about what happened on Oct. 2, 1983, in Washington when 18,000 Ukrainian Americans staged a rally in front of the Soviet Embassy, although I was eager to find out whether he and Mace were there. Jimmy had never mentioned his participation in this political event. Orest Deychakiwsky, staff adviser to the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (Helsinki Commission), read an open letter during the rally. The message is still topical, considering the Russian Federation’s critical attitude to the recognition of the 1932-1933 Famine as an act of genocide, which was voiced during the CIS summit in April 2006.

“The Holodomor was a deliberate act of genocide, the only man-made famine in world history, and although different methods were being applied by the Soviet government, the objective was the same: to destroy Ukrainian national identity. Your current leadership knows about the genocidal famine and the current policy of Russification, but it continues to deny this.”

Eighteen years have elapsed since that rally in front of the Soviet Embassy in Washington. The USSR is history, but the embassy building is still there, which the Russian Federation inherited along with great-power ideology and responsibility for the past. Perhaps it would be best to disown such a dubious heritage, considering that peasants in the Don region were also dying during this famine and Mikhail Sholokhov, the author of the novel Virgin Soil Upturned, repeatedly told Stalin about this. The historical fact of this crime must be acknowledged, all the more so as during this tragic period the government of the RSFSR was not involved in the ideology and practice of genocide. Apparently, certain circumstances are preventing Moscow from taking this step, since official Moscow is loath to return to the past, not wishing to “disturb” the present.

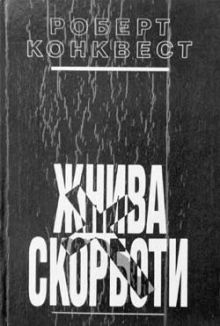

Robert Conquest and I discussed the need to preserve and study archival documents on the Holodomor, which are stored in Ukrainian and Russian archives. I have an autographed copy of his English-language book Harvest of Sorrow. It appeared in print in 1986 and its Russian version was published in 1988. The Ukrainian version appeared in 1993, although separate chapters were published in the journals Dnipro, Trybuna Lektora, and Kyiv in 1990. Somehow the 1986 original foreword was not included in the Ukrainian translation. In it Robert Conquest thanks James Mace and his Stanford and Harvard colleagues for their cooperation. Judging by reviews in the Diaspora press, the book was written in the spring of 1984 and the text was discussed during a forum of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. The foreword’s date also looks logical: 1985, meaning that it was written before the book appeared in print.

When Conquest’s monograph was published 20 years ago, it sparked great debate. Soviet historians tried to refute some of the facts; Western political scientists upheld them; while the Ukrainian Diaspora used it to substantiate the fact of this act of genocide through scholarship. Its publication coincided with Gorbachev’s perestroika campaign, although the book itself marked the appearance of a new perception of the causes and consequences of the Holodomor in Ukraine. It served as fresh impetus for further research, destroyed existing stereotypes, and encouraged us to revise our history.

It taught us to identify gaps in our history as blank pages hiding entries covered in blood. From the rostrum of the 18 th All-Union Party Conference held in Moscow in 1988, Borys Oliynyk spoke about the 1933 Famine as a tragedy endured by the Ukrainian people. In the following years a series of archival documents on the Holodomor appeared in print. Yevhenia Shatalina and I published them in Ukrainskyi istorychnyi Zhurnal [Ukrainian Historical Journal] in 1989. The process had been launched, and in the next several years we published several volumes of Holodomor eyewitness accounts, a collection of archival documents, dozens of monographs, and held scholarly conferences on the subject.

Although sufficient efforts seemed to have been made, the process stalled when it came time for the official recognition of the Holodomor as an act of genocide. From a purely scholarly question it had acquired markedly political hallmarks. In May 2003 the Communist Party of Ukraine, then with a sizable faction at the Verkhovna Rada, refused to acknowledge the Holodomor and marched out of the parliamentary hall. These are strange people to whom ideological prestige means more than Christian consciousness: all those peasants who starved to death were not buried in accordance with the Eastern Orthodox rite.

Over 60 countries are observing the anniversary of the Holodomor in Ukraine; many of them have handed down due political and legal judgments and confirmed the act of genocide, i.e., a crime against humanity. We must officially recognize the Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people; no one will suffer any political losses. On the contrary, this will serve as proof of the start of an era of new political morals.

For me it was important to hear Robert Conquest’s political and legal assessment of the Holodomor in Ukraine. I asked the learned professor if he had revised his view of the Famine as an act of genocide, as presented in his book, now that 20 years have elapsed. He gave a definite no, and then bolstering his argument as a true researcher, said that Holodomor is the best term, because it means a concrete historical form of mass physical destruction, because peasants died en masse at the time as victims of a man-made socioeconomic phenomenon, not a disaster. The term “terror-famine,” applied in The Harvest of Sorrow, related to the political causes of the Holodomor — in other words, it was a deliberate effort aimed at bringing about a famine that would kill, which is none other than an act of genocide. When we use the term Holocaust, the scholar went on to say, we have in mind the Nazi methods and forms of massacring Jews in concentration camps, which falls under the 1948 genocide convention. I was very impressed by his tolerant, scholarly approach to formulating the causes of the Holocaust and the Holodomor.

For a researcher the best reward is public recognition of his findings and their social value. I presented Stanford University with the monograph The 1932-1933 Famine in Ukraine: Causes and Consequences (2003). Dr. Conquest commented on it positively and then gave me a copy of his book signed “With best wishes.”