The fall has come to Ukraine, to be followed by winter with its unpleasant surprises in terms of soaring prices, the plummeting hryvnia exchange rate, and the presidential election. The presidential campaign has begun, albeit unofficially. To be precise, this campaign has been underway for five years in the form of scheduled and snap parliamentary elections and the phantom of the Verkhovna Rada’s (self-)dissolution.

Among the sure signs of the presidential campaign are the openly populist political ads and commercials, blockaded VR rostrum, billboards, and amendments to the election laws.

In fact, altering the election law prior to the next elections has become traditional in Ukraine. As a result, instead of a balanced approach we have a bunch of non-systemic changes that are internally uncoordinated, controversial, and haphazardly adopted. The VR speaker noted that the Law of Ukraine “On the Elections of the President of Ukraine” will be altered, upgraded, patched up, and adjusted until the end of first round of the presidential elections, while in the second round and that in the second round the process will be out of control. In other words, no one knows what course the election laws will take; it is unpredictable and non-systemic precisely when the election campaign is underway.

This time the majority in Ukrainian parliament (not the political majority responsible for its acts but the arithmetic majority, where responsibility is an extinct notion) didn’t even bother to mention the necessity of voting on the elections code. When voting on the Law of Ukraine “On Amending Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine On the Election of the President of Ukraine,” this majority was guided not only by political expediency (as seems to have become standard practice), but also by a desire to demonstrate their strength. This demonstration of strength prevented the Ukrainian parliament from taking into account the President’s remarks most of which were worth considering.

Specifically, this is true of the President’s remarks concerning the increase in the monetary deposit to be submitted by the political parties (electoral blocs) or by each presidential candidate—from 500,000 to 2,500,000 hryvnias (Article 49 of the Law of Ukraine “On the Election of the President of Ukraine” in the new wording). Combined with the cancellation of the requirement to collect the specified number of signatures to prove popular support, this innovation is designed to monopolize the passive right to vote by oligarchic groups and will actually transform the monetary deposit into property qualification. Once the new clauses of the Law of Ukraine “On the Election of the President of Ukraine” take effect, this right to vote will apply to persons who can afford to pay 2,500,000 hryvnias for access to the presidential campaign regardless of electoral support.

Conversely, democratic principles require a lower monetary deposit and a greater number of signatures for a given presidential candidate. Regrettably, democratic principles do not agree with those of political expediency in Ukraine.

Canceling the clause on signatures simplified the process of nominating so-called technical presidential candidates. From now on they will both distract the electorate from voting for a real candidate and secure the presence of their people in the election commissions, because each candidate will have his or her representations on these commissions.

The new wording of the Law of Ukraine “On the Election of the President of Ukraine” simplifies the decision-making procedures on the part of the election commissions. Thus, revised Articles 13, 29, and 30 (9) read that such decisions can be made by the ordinary or qualified majority of the commission members present (rather than the majority of the commission, as worded originally).

President Yushchenko was perfectly right in noting that these innovations were feared because they could result in destroying the mechanism of monitoring the election process, destabilize the performance of the election commissions, etc.

The Verkhovna Rada made some changes to the procedure for determining the results of the presidential elections and their official promulgation and the court appeal procedure. Thus, the new wording of Article 84 (3) of the Law of Ukraine “On the Election of the President of Ukraine” reads that the Central Election Commission draws up a “protocol” based on the results of the election. However, on the strength of the new wording of Article 82, Article 172 (3), Article 176 (6) of the Code of Administrative Procedure, a court of law can accept only appeals concerning acts or inactivity on the part of the Central Election Commission.

In other words, these legislative innovations make it impossible to legally challenge the CEC findings, thus denying the participants in the election process their constitutional right to judicial protection. It would be interesting to know if this terminological confusion (“protocol” vs. “decision”) is intended.

President Yushchenko had every reason to veto the bill “On Amending Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on the Election of the President of Ukraine.” His veto was overruled by 325 votes in parliament. In fact, none of the President’s suggested amendments was taken into account, most likely because the Verkhovna Rada wanted to vote down any proposal made by Yushchenko, even if acting contrary to common sense.

Yushchenko refused to sign this law. It will be signed by the Verkhovna Rada speaker and will take effect as per Article 94 of the Constitution of Ukraine.

Whereas the stand taken by the head of state can be regarded as a resolute refusal, the stand adopted by the speaker is intriguing. Commenting on the President’s intention to challenge the constitutional validity of the Law of Ukraine “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on the Election of the President of Ukraine” in the Constitutional Court, Speaker Volodymyr Lytvyn noted that the CC could indeed find reasons for recognizing some of the clauses of this law unconstitutional, but in this case the election process will be derailed.

His stand in the matter calls forth an almost rhetorical question about the degree of guilt and answerability if the upcoming presidential campaign fails. Who will be held responsible? The current head of state who will challenge certain clauses in the current election law, the Constitutional Court that will pronounce these clauses unconstitutional, or parliament, which consciously passed an unconstitutional bill?

The coming presidential election can be disrupted not only because of the Constitutional Court’s ruling. This law has another tangible drawback that no one pays attention to. This flaw led the Supreme Court of Ukraine to pass an equivocal decision in 2004. It is a time bomb that was planted under the election process back in 1999.

Ukraine’s election laws have undergone a number of changes. The first presidential election law was adopted on July 5, 1991. It was revised and adopted on Feb. 24, 1994 and then replaced by the Law “On the Election of the President of Ukraine” of March 5, 1999. This law has been amended several times and the final wording was adopted on Aug. 21, 2009.

Strange as it may seem, each new redaction was a change for the worse. First, the passive right to vote was narrowed (by increasing the deposit sum). Second, clauses were added (the number of articles grew from 45 to 105) while key provisos were lost.

In particular, the new wording of the Law of Ukraine “On the Election of the President of Ukraine,” compared to that adopted on March 5, 1999, lacks the clauses that specified procedures to be followed if the election results were rigged. Unlike the March 1999 wording of the law, the previous redactions specified the procedures for holding a re-election if the original results were recognized as invalid.

For example, Article 44 of the law adopted on Feb. 24, 1994, reads that one of the reasons for repeat elections is the annulment of the previous election results. Under Article 41(5), the presidential election could be invalidated if there were violations of the vote-counting procedures that had a tangible effect on the outcome of the elections. Regrettably, these key clauses were omitted—accidentally or purposely—in the March 5, 1999 redaction. From then on there has been no formula for announcing a presidential election invalid on the legislative level.

Under Article 15 (4) of the current Law of Ukraine “On the Election of the President of Ukraine” and the new redaction of the law, repeat elections are held if (1) not more than two Ukrainian presidential candidates are on the ballot and none has been elected; (2) all Ukrainian presidential candidates on the ballot stepped down before the date of the election or before the date of a repeat election.

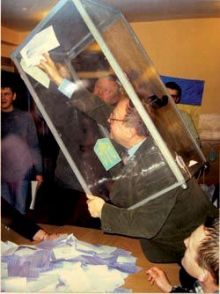

In other words, violations of the electoral procedures, including massive falsifications, do not suffice to warrant repeat elections. Moreover, this law does not contain an answer to the question of finding a way out of a political crisis caused by rigged elections.

Let us recall the ruling of the Supreme Court of Ukraine made on Dec. 3, 2004. It was a political one, in terms of form and contents. However, any ruling made by the Supreme Court of Ukraine is a recognition of the victor in the first round of elections (as the supporters of the presidential candidate Viktor Yushchenko insisted at the time), assigning the date of the repeat elections or another round of the elections (precisely the decision made by the Supreme Court). This would be a political decision, because the court had no opportunity of making a legal, nonpolitical decision, because the election law had no such clauses at the time (just as it doesn’t have them now). In such a legal vacuum and with the situation being aggravated by political confrontations, the judiciary branch of power is doomed to make political decisions.

The events of 2004, unfortunately, have not resulted in a principal revision of the election laws. The gap is still there. This means that the outcome of the presidential election will depend not on the voice of the people but on political decisions that will be made as demanded by the political situation.

Remarkably, politicians of all levels keep warning about tensions in the coming election campaign and the strong likelihood of massive falsifications and abuses of office. However, none of them seems determined to take any legislative measures to prevent such negative phenomena or overcome their consequences. This can only be regarded as undermining the principles of people’s sovereignty.

It appears that the coming presidential election will be held in accordance with the law adopted on Aug. 21, 2009, including a number of additional clauses that are constitutionally dubious.

Oleksandr Yarmysh holds Ph.D. in law and works as a professor; Alina Cherviatsova is an associate professor with a Ph.D. in law.