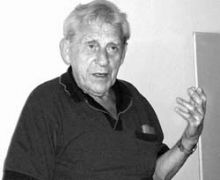

This energetic, gray-haired gentleman, who looks much younger than he actually is (he turned 80 on September 4), is a living legend indeed. Loftiness is quite justifiable in this case. The Zhytomyr-based veteran construction worker Franz Brzezycki is Ukraine’s only surviving ex-prisoner of the Majdanek extermination camp. The last one...

When the war broke out, 16-year-old Franz Brzezycki was living in his native city of Zhytomyr. Yet, even at this young age, he had already borne the stigma of a “son of enemies of the people” for three years. His parents were arrested in 1938. Although his mother was soon released, his father was convicted for belonging to a fictitious Polish military organization. (Karol Brzezycki was posthumously rehabilitated only eighteen years later).

The first eighteen months in Nazi-occupied Zhytomyr marked a period of Franz’s (or Frantiszek, as his friends called him) active involvement in the underground movement and cooperation with Slovak resistance fighters. Incidentally, it was Brzezycki who brought Zhytomyr underground militants in touch with the guerrilla force led by the legendary Slovak commander, Hero of the Soviet Union, Jan Nalepka.

The Germans were quick to discover the activities of the young Zhytomyr resident and soon arrested him. The young man was on death row for several weeks, where he awaited execution by firing squad. But fate chose to subject him to a far more terrible ordeal.

MORE HORRIBLE THAN DEATH

One night he was taken out of his cell, brought to the railway station, and shoved into a freight car jam-packed with people. The two-week-long “journey” on a freight train ended on February 13, 1943 — that day 1,240 unfortunates (from Zhytomyr, Berdychiv, and Shepetivka) arrived at Majdanek, a Nazi concentration camp located on the outskirts of Lublin.

Majdanek was built in the fall of 1941 by Soviet prisoners of war. The camp’s cynical name (which sounds almost the same in Ukrainian and means “playground”) was meant to mislead the world community about the true size and scale of this “death factory.” The over 100-hectare camp was in fact a hair-raising “waste-free enterprise.” The ashes of cremated prisoners were used as fertilizer, clothes and footwear were reprocessed, and valuables (including gold dental crowns) were taken to German banks. During the war the Nazis exterminated a total of 1.5 million people at Majdanek.

Franz Brzezycki spent more than a year at Majdanek. It still hurts him to talk about that horrible year: all the details of each infernal day still linger in his mind.

“LESSONS OF SURVIVAL”

He still remembers a hefty Russian, who said to the newly-arrived novices, “Forget your names — we are just numbers here. Stick to one another and maybe somebody will survive.”

He also recalls a Pole, a participant in the Warsaw uprising, who was dying in the infirmary. Very rich before the war, he was now lying and quietly moaning, “I would pay a million for a sip of tea.”

He cannot forget the customary, and thus terrifying, picture: naked (only covered with dirty blankets) and haggard prisoners (“goners”) are traipsing one by one across the camp courtyard to the guffaws of the guards. They are heading for the gas chamber.

Several times Frantiszek escaped death by a hair’s breadth. Once, when he was unloading wooden planks, he became so weak that he stopped and leaned against a wall. A sadistic SS guard, who liked kicking prisoners to death, went toward him with a grin. But the vorarbeiter (foreman) Jozef Singer, a Polish Jew, overtook the Nazi halfway. After bawling out and whipping Franz, he pushed him off the SS man into a crowd of working prisoners. In the evening he came to the barracks and said to the young man, “I’m sorry I thrashed you in the morning: that was the only way to stop the Nazi butcher.” From then on they were close friends. The experienced Jozef taught the young Franz a lot of important “camp survival lessons.” Still, fate showed no mercy to Singer: he met his death together with 18,000 of his compatriots, who were shot at Majdanek on November 3, 1943.

Brzezycki miraculously escaped death a second time in the camp’s infirmary. “An old wound began to bleed again (a reminder of German ‘hospitality’ in Zhytomyr’s secret police dungeons). The camp doctor Novak, himself a prisoner, stemmed the bleeding and performed surgery, which prevented gangrene.” Mr. Brzezycki reminisces. “I was still in the infirmary when some SS men suddenly broke in — they had a habit of taking emaciated ‘goners’ to the gas chamber. With no other way out, a friend of mine and I dove into a large slop tank by the wall and sat out the roundup.”

In addition to excruciating work and the tortures that were inflicted by the security guards, camp life was full of other “trivia” that one had to get used to very fast, for example, the absence of such a thing as a spoon — they had to pick up food with their hands.

“RUNNING” NUMBERS

There were numbers instead of names. Brzezycki became No. 10741. He later learned that those were “running” numbers: several prisoners would bear the same number by turns, i.e., those still living would take it over from the dead. (This is why the total number of number tags never exceeded 12,000). Next to the number was the letter R (Russian), or P (Pole), or a six- pointed Star of David.

There were thousands of fleas whose bites sometimes seemed worse than death. Zhytomyr prisoners took their first bath three months after arriving at the concentration camp. That was a special day in many respects: not only did the prisoners take a bath, but also many of them were given plain clothes (jackets, trousers, and caps) in lieu of striped overalls. And, what is more, almost no one was beaten up. It turned out that a Red Cross delegation was visiting Majdanek that day, and the administration tried to create the impression of a “showpiece camp.” The memory of that unusual day surfaced again forty- five years later, when Franz Brzezycki came across the book Majdanek by Jozef Marszalek (Warsaw, 1987), where he recognized himself in one of the photos (captioned “Building a Road, 1943”) — in which he is wearing the above-mentioned civvies.

In April 1944 Brzezycki, one of the 1,500 strongest prisoners, was transferred to the Grossrosen concentration camp and soon after to Leitmeritz, a camp in Bohemia. Prisoners were not killed there: the Nazis could not afford this kind of “luxury” because the front line was very close and Germany needed a lot of work hands. So Franz remembers the year he stayed at Leitmeritz as primarily a time of backbreaking work in underground quarries and a terrible outbreak of typhoid that mowed down many prisoners. The camp was liberated by Soviet troops on May 8, 1945.

GULAG

A few days later Brzezycki was drafted into the Red Army. Their reserve regiment was stationed first in Dresden and then in Kowel. It was there that fate decreed another ordeal for the young man. He stood up for a friend of his, also a former concentration camp inmate, whom the counterintelligence officer had been tirelessly “grilling” (“Why were you taken prisoner?” “You’re a spy, aren’t you?”). So he said a few “heartfelt words” to the officer. The next day he was arrested for “disobedience.” When they looked into his dossier (father an “enemy of the people,” mother also “did time”), they quickly trumped up a new charge” — counterrevolutionary activities.”

“I was so affronted: I had survived Nazi camps and now our side was calling me an enemy! So I bluntly told the counterintelligence chief during an interrogation that I would surely escape,” says Mr. Brzezycki.

Escape he did! He and a friend (also politically suspect), scantily clad and barefooted, tied up the guards and ran away on a dark autumnal night. Roaming the thick Volyn forests for several months, Franz finally returned to his native Zhytomyr. His mother nearly fainted, for she thought her son was dead. (After the war the regional Communist Party committee officially told her that the Nazis had executed Franz Brzezycki in Zhytomyr in early 1943).

He hid for four years, almost never leaving the house. Still, one of his neighbors “blew the whistle” and he was nabbed in 1950: he was given a speedy trial and a sentence: ten years in the GULAG. After serving five years in Kemerovo, he was rehabilitated, had his sentence quashed and came back home in 1955.

This is the kind of youth he had: two years in Nazi extermination camps, four years in hiding, and five years in Siberia. Mr. Brzezycki likes telling a bitter joke, “I graduated from two universities. The crazy Fuehrer was president of one and the Father of All Nations — of the other.”

A VANISHED MANUSCRIPT

Two years ago Franz Brzezycki kept the vow he had made to hundreds of his Zhytomyr fellow countrymen who died in the Majdanek inferno: from there he brought an urn with human ashes, which was solemnly reburied in Zhytomyr. In late April of this year he celebrated the 60th anniversary of liberation from Majdanek. Back in 1944 Soviet soldiers liberated 1,200 half-dead people from the camp — Poles, Jews, Russians, Ukrainians, Slovaks, etc. About forty ex-prisoners, still living and strong enough to travel (most of these people are over eighty) visited the Lublin-based Majdanek memorial complex in 2004. Ukraine was represented by Franz Brzezycki, the only citizen of our country among the surviving inmates of Majdanek. The Poles, aware that Frantiszek’s reminiscences are invaluable, call him “the last living page of history.” But are Ukrainians aware of this?

A few years ago Mr. Brzezycki’s place was broken into: the robbers walked off with, among other things, the manuscript of his book on Majdanek. Despite every assurance, the police have so far found neither the criminals nor the manuscript.

In 2000, the Zhytomyr regional branch of the Anti-Nazi Resistance Fighters’ Organization expelled Brzezycki on the grounds that he had joined a Victory Day festive demonstration with a Polish flag in hand. (It should be noted that Mr. Brzezycki is one of the most active members of Zhytomyr’s Polish community). Soon realizing the absurdity of their decision, the organization’s leaders called it a “misunderstanding.”

It was not until last year that Mr. Brzezycki obtained war veteran status — sixty years after the Majdanek inferno.