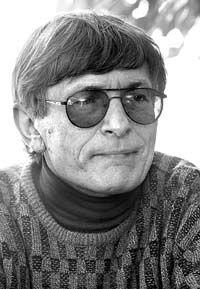

Before the third round of the presidential election in Ukraine, when the winner’s name had yet to be formally announced-and when few if any doubted the winner’s name-the noted Ukrainian philosopher and sociologist, Yevhen HOLOVAKHA, deputy director of the National Academy’s Institute for Social Studies, demonstrated a remarkably calm and balanced stance in an interview with The Day . He said that the government that was taking power on the crest of the wave of mass disillusionment with the existing regime had received a great deal of trust from the masses. However, the big hopes that were being placed in the new government might well result in a great deal of disappointment later. Naturally, mass disillusionment is not on the agenda. Yevhen Holovakha insists, however, that there is a great risk that the current popular administration will get into society’s bad books, as evidenced by the steps that have been taken and declarations that have been made by the former Maidan leaders. In Mr. Holovakha’s opinion, their implementation may lead to dire consequences for Ukrainian society. Under the circumstances, the main task for the intelligentsia is to help the new government avoid making mistakes- precisely what this sociologist, who has spent many years studying domestic and international social trends, is trying to caution against in the following interview.

TREATING PATHOLOGIES TAKES YEARS

What do you think of the new government’s first steps and statements? Do you have any concerns or, perhaps, positive comments?

Holovakha: In advanced democratic countries power changing hands is not a shock or stress for society, since all it boils down to is making certain changes in the national policy in keeping with the ideas of the winning political force and current demands. In Ukraine, the new regime isn’t regarded as a successor to the previous one, trying to take constructive steps and correct previous mistakes; it’s viewed as a clear-cut alternative. It’s like when Leonid Kravchuk was replaced by Leonid Kuchma. In this sense, the masses’ positive expectations are what count. In a country that was doomed to live for so many years according to the laws of extreme transformation, popular expectations prove just as extreme. People want speedy changes for the better, a kind of harmony in the life of society.

The new government is responding enthusiastically to these expectations and is taking quick steps aimed at distinguishing itself from the previous regime. However, this accelerated implementation of extreme expectations rarely leads a country to a decisive turn for the better. The thing is that mass expectations of better times seldom agree with the real resources. There is a psychological phenomenon known as “unrealistic optimism.” For example, when young people are polled about their expectations, they tend to visualize bright prospects, but see their peers’ immediate future in darker colors. In other words, they are capable of objectively assessing other people, their potential, etc., but they can’t see themselves objectively. Therefore, considering every individual’s expectations, by this I mean the way they would like to live, the overall result is the phenomenon of “unrealistic expectations.” And so the government should not follow the principle of implementing any such “unrealistic expectations” in the first place.

On the other hand, from the outset we have been hearing a number of loud and decisive statements from the new government, which envisage changes in all spheres; that property must not be owned by those who obtained it illegally; that all bureaucrats in charge of state-run agencies and institutions must be replaced, regardless of their individual professional performance; that the Academy of Sciences should be abolished; that decisive measures should be taken to stop the flow of contraband across Ukraine’s frontiers; that corruption and the practice of giving and taking bribes should be quickly eliminated. In other words, problems that took shape over decades must be eliminated overnight.

There is a splendid medical principle: curing a chronic disease takes about as long as its development does. A chronic illness is a lengthy process of the pathological development of the organism, whereby the very pathology becomes part of the system. An individual gets used to living in a pathological state, forming an adaptation syndrome of sorts. Thus, cardiac patients can live for 70 to 80 years, while other, outwardly healthy, individuals may die of a sudden heart attack. Of course, the social environment is not as simple as the biological one, yet certain analogies are in order.

That same adaptation syndrome appears to have evolved in our people, after living for 15 years in extremely difficult conditions, years that in many respects proved contrary to what is generally regarded as a normal living standard, years that were horribly unfair. However, the last couple of years were a period in which the people were gradually adjusting themselves to a system that they hadn’t been able to accept in the mid 1990s, on principle. I believe that the cleverest approach to the situation would be to adopt soft, well-considered measures aimed at ridding the social organism of the pathologies that have accumulated there.

THE RISKINESS OF GOOD INTENTIONS

What do you think is wrong with the new government’s intention to end corruption and contraband?

Holovakha: Their rash and radical decisions. Every sober-minded economist knows only too well that the instant or month-long shock inflicted on the corrupt customs authorities will not lead to a result whereby one month later they will emerge immaculately clean. On the contrary, they will become smarter, after getting over the shock, and begin devising ways to receive higher bribes as high risk pay. Of course, contraband must be fought against, but it should have an altogether different character; it must be a well thought out and long-term campaign based above all on economic methods.

The same is true of the struggle against corruption. Statements about instantly ending corruption are populist slogans. Regrettably, such statements aren’t backed by any real mechanisms. Of course, one can say that we’ll throw all those bribe-taking bureaucrats behind bars. However, all of them would be tried by judges, most of whom are also involved in or with corruption. In other words, corrupt officials will be in a position to pass judgment on other corrupt officials, with a certain force positioned above them, which upon closer inspection cannot be cleansed of corruption, either. There can be no radical means of combating corruption. If we say that most state bodies and agencies are corrupt (which is true in most cases), it means that we must work out a serious strategy, above all an economic one. For example, we must realize that a bureaucrat, given a certain modus vivendi and operandi, will be immune to corruption. However, we are told that raising the salaries of such bureaucrats is not a solution to the problem. Leaving aside what the bureaucrat earns, if the system is such that besides his salary, a bureaucrat can always find ways to obtain dividends from his privatized civil servant’s post, he will still take bribes. This problem should be solved in a different way, by raising the national living standard rather than adding to bureaucrats’ salaries. Historical experience shows that corruption can be counteracted, more or less, when the living standard reaches a critical mark, when the so-called average statistical individual has not only the need to survive, but also free time and extra money to pay his defense counsel in a lawsuit against a bribe-taking bureaucrat, defending what he believes is a just cause; when he can afford to feel independent of the state. There are such people in society now, but not enough of them. If the living standard keeps rising for the next few years, it is safe to assume that corruption will stop being a widespread phenomenon.

As for non-transparent privatization, yes, it is non-transparent and unfair. However, as a sociologist who compares the social health bills of people engaged in the public and private sectors, I must state that the health bills in the latter sector look considerably better. And the gap is widening. By this I mean that whatever happens in the future, there is a large stratum of people who will have gained something from the privatization process. I think that it’s a more important criterion than whether or not such privatization was carried out in keeping with the fair rules of the game, all the more so as the notion of social justice is too complicated to be properly interpreted by bureaucrats.

Fortunately, the economic sphere is quite stable and resists such measures. However, rash steps taken in the political and cultural domains can cause considerable damage. Deputy Prime Minister Roman Bezsmertny declared, for example, that all the great reformists have changed things, including the Ukrainian map. Frankly speaking, I didn’t grasp the idea of uniting our oblasts [i.e., administration regions], except that all reformists were expected to change things; and nor did our society hear any more or less reasonable arguments. As an expert in my field, I understand that this approach can have very bad consequences. However, if a number of cities lose their regional center status, they will fall into decay under the conditions of our overcentralized system. This wouldn’t be painful in another system of regional organization. For example, in the United States the status of a city is not determined by its administrative significance. There, even a small backwater town can become the capital of a state, whereas a megalopolis with millions of residents may remain an ordinary city. In Ukraine, the loss of administrative status may prove disastrous for a city, because the city would lose development funds. Perhaps it would be fair if we didn’t invest in these cities. But who knows about the consequences? Who made the calculations? Once again we need serious expert work here, as well as discussions of various opinions and representatives from the regions subjected to such experiments.

The same is true of the Academy of Science. When we hear stunning statements to the effect that the academy can be liquidated simply because we lack brilliant inventions, any sober-minded individual will see an altogether different reasoning. Our academy is the only place where intellectual freedom can be developed. This is precisely why, unlike, say, institutions of higher learning, whose administration is completely dependent on the ministry, the Academy of Sciences has always been self-governing, even during the Soviet period. That is why they couldn’t deprive Academician Andrei Sakharov of his titles, meaning that any sober-minded individual will see through such statements by the government, namely their intention to destroy yet another center of liberal free-thinking, an environment that gives rise to free and independent individuals who are hated by any administration. In addition, behind this statement lurks a basic misconception of the functions vested in scholarship. After all, in addition to discoveries, it has countless other tasks. One of them is assessing the performance of the government with regard to the conformity to modern demands.

SEARCHING FOR “OTHER RATS”

Perhaps the new government wants to make the most painful changes as soon as possible, before the credit of popular trust is exhausted?

Holovakha: Generally speaking, scoring a quick victory is easier said than done. To this end, public opinion often tends to accept words rather than deeds, taking them at their face value. However, the government must think about the future rather than today’s gains. Do you know the difference between today’s Ukrainian youth and their counterparts who have spent decades in the US? Our colleagues surveyed them, requesting answers to only one question: “If offered $200 immediately or guaranteed $500 in half a year, which option would you prefer?” Most of the Ukrainian respondents said they wanted the money right then and there, and our government differs little from them, whereas industrialized governments prefer $500 guaranteed in half a year’s time.

Remember how the new government, when it was the opposition, accused the previous regime of populist moves? Populism, however, wasn’t characteristic of that regime, which was actually closed off from Ukrainian society. It was a self-centered regime, so only bits and pieces of information could be gathered, often in the form of hearsay. The new government, aware that adopting this image would be hazardous, has chosen the road of broad populism, meaning that they prefer basking in the limelight, to love and be loved in return. From this point of view, a number of measures may prove extremely popular. People always love to hear and watch their VIPs, how they live, etc. People also enjoy being told that the government is about to put an end to some negative phenomenon or another. Not accidentally, the new government is enjoying a high level of popular trust; big hopes are still being placed in it. From the standpoint of immediate results, such measures of the government are yielding certain dividends.

However, what’s the difference between an incompetent government and a competent one? It is that an incompetent government wants to become popular here and now, whereas a competent one, even though it also desires popularity, wants above all to solve problems that can cause a national crisis or future cataclysms. In 2002, prior to the elections, Viktor Yushchenko quoted me in his theses, saying that the sociologist Holovakha very aptly identified the regime as a momentokratiya [instant autocracy]. Apparently what he meant was that he and his people were different, that they would come up with a new program of action and strategy that would differ from those of the regime, which focused on immediate, short-lived achievements. Today, however, he is at risk of hearing the opposition leader refer to that very quote.

It’s possible that the new government is testing the waters by proposing radical measures. If so, this tactic should be regarded as dirty campaign technology that has long been practiced elsewhere in the world. In Russia, this function is discharged by Zhirinovsky, who first voices a radical idea and then, if it is enthusiastically accepted, the Russian state makes an appropriate decision. If the Ukrainian government’s strategy lies in this, the media and public response becomes extremely important. But I believe that the path the new Ukrainian government has embarked upon is one of trial and error. By the way, this approach is characteristic of people who are struggling to solve new problems. True, it’s germane to incompetent people. Competent people use much more advanced methods.

Generally speaking, expecting competent people in power would be naХve, considering the harsh confrontation with the previous regime. Personally I’d never expect a protocracy — power wielded by truly competent individuals — to emerge in Ukraine, much as we would want to have this sort of government. As we know, protocracy exists only in theory, since incompetent individuals cannot rule competent ones, and because it’s useless to try to have competent ones keep incompetent ones under control. So, more often than not, incompetent people come to power. However, these people must have a sense of politics, a political talent of sorts, notions that no one has rationally formulated. Words like “charisma” and “leadership qualities” boil down to the ability to find competent individuals. So far I don’t see this ability in the new government.

There is a desire to have protocracy, even if it is at the level of the so-called other rats. Do you know how rats build their communities? There is a king rat, the strongest and most aggressive one that keeps the rest under control. He gets the best food and other earthly pleasures before all the rest. However, the burden of the community’s survival rests on the shoulders of all those “other rats” that are more advanced intellectually. Therefore, selecting these kinds of “other rats” is a necessary condition for setting up a proper government.

Perhaps the statements being made by the new government should be interpreted as manifestations of basic idiocy. Incidentally, this could be a good option. No people newly assigned to responsible posts can avoid making mistakes and displaying acts of idiocy. Total populism appears to be a much more hazardous option, when feverish attempts are made to accomplish something for everyone’s good, doing so in a manner noticeable to one and all and winning the public’s love. Such efforts are not selfless and have everything to do with the next parliamentary elections; they can produce lasting unwelcome consequences for Ukrainian society. The task of the intellectual elite, which adopted a rather specific stance during the last presidential campaign, resolving to attack the leader of the opposing side rather than traditionally remaining politically inactive, consists in pointing out to the government that its actions may be dangerous not just to itself but everyone else in Ukraine.

What does this danger consist of?

Holovakha: Primarily in the possibility of forfeiting the process that is advancing social development. After all, a society evolves not only as a regime but also over and above it. In the past five years, regardless of who held the post of prime minister, there has been an objective social evolutionary process, as the only way to solve global problems, such as corruption, misery, abuse of office, and so on. But the structure of this growth is very fragile. It can be easily shattered. A rash decision made today can cause us to lose this evolutionary process, and it will take years to restore it.

You mean that our society can evolve outside the current regime?

Holovakha: A lot of criticism has been directed at the non-transparent formation of this government. However, I, for one, don’t believe that government should be that transparent. God forbid if all of us become that transparent; we wouldn’t be able to communicate with each other, realizing what’s hidden behind that opaque layer. Making decisions away from the public eye is normal practice. It is quite another thing that we have people who came to power with no experience in the field, moreover, people who are bound by family or other affiliations. Valery Vorona, the director of our institute, once aptly put it that the notion of politykum [political environment in Ukraine] is an interesting one. It was introduced by our political scientists, but they most likely they are not aware of the deeper meaning of this word: a combination of two concepts: polityka (politics) and kum (a reference to Kumivstvo meaning nepotism), which boils down to paternalism. The latter is characteristic of the Ukrainian political elite.

Of course, when the government was being formed, nepotist considerations were not uppermost; the main thing was whether a given person was popular with the Maidan. This government could be described as the result of a spontaneous, popular outburst of indignation; hence all those incompetent governmental statements. More than enough examples could be cited, including the absolutely odious case of a suspected killer described as the definite murderer. Or the practically instant determination of the cause of Kravchenko’s death: suicide. Or the curious case of the government meddling in the cultural sphere, when a ranking bureaucrat suddenly decided to change the Eurovision contest terms and when the noted Ukrainian soccer player and Dynamo Club coach Oleh Blokhin found himself being persecuted, much to our soccer rivals’ merriment.

“THERE’S A GRAIN OF TRUTH IN EVERY JOKE”

The 10 years of the previous government’s rule are referred to as the “Kuchma regime.” The new government is striving to do everything so as not to resemble the old government. But how long do they expect to remain new given the old conditions? And what are the chances that in a year or two we’ll be calling it the “Yushchenko” regime?

Holovakha: I call this “memory metal.” Some metals can be returned to the original state after processing. There is a similar social trend: memories of a certain social order where every element occupied a strictly designated place. If we say, for example, that the new government can replace the previous regime and start running this country in an entirely different manner, it’s about the same as saying that a new society emerged after the elections and launched a new way of life. New people can come to power. There are such examples in history. In China, the uprising of the Red Eyebrows led to a situation in which slaves overthrew the imperial house and established their own imperial rule. However, the paradox is that relations between the regime and society didn’t suffer in any way. A new kind of imperial rule emerged, which owned new slaves and kept different bureaucrats under control, although the new regime was essentially no different from the previous one simply because the same rigid system was still in place. Even if those former slaves had wanted to build a free country in imperial China, they would have failed. Of course, we’re living in a modern flexible society, so we have more opportunities for major substantial changes.

I won’t dwell on what those who are currently in power actually wish to accomplish; whether they want simply to wield power in order to change things for the better. I believe that people in power, provided they are truly sober-minded, want to enjoy their authority and make this society better. The real path to be embarked upon by any government wishing to introduce progressive shifts is along the lines of well thought out and consistent reforms. Implementing such reforms doesn’t mean executing a U-turn. It means working out realistic documents envisaging certain consecutive stages of reform. The old regime also worked out programs, but they were all ornamental elements for a certain kind of political practice that had nothing to do with such a stage setting. Programs aimed at producing real results should be developed in collaboration with the most competent domestic experts, and their foreign counterparts if need be.

Believing that some miracle- working decisions on the part of the new government can essentially change the situation in this country is naХve. What alarms me (I’ve mentioned this before) is the possibility of ending up with a primordial government rather than a feudal form of government. I spoke with many people before the elections; they really believed that Yushchenko and Tymoshenko would come to power and work miracles. This is primordial mythical psychology, when people believe that instant changes for the better are possible but fail to realize that such changes are not objectively substantiated. The essence of this primitive conception is that it is acausal, in other words, unsubstantiated. It is an ugly duckling turning into a beautiful swan or an aging derelict eating a magic rejuvenating apple. People realize that there are no such apples, but they want to believe in the tale; hence their confidence in the new people who have come to power and are able to work miracles. Our politicians experienced a number of ordeals, including the Orange Revolution, and emerged as Prince Charmings, but we know what happened to the tsar [in Pushkin’s Golden Cockerel, after he took a dive into a cauldron with boiling milk to become young again and win the princess’s love]. Yet if the masses still believe in such fairy tales, the situation isn’t as bad as it seems. Mass consciousness traditionally tends to accept such fairy- tale notions. But when people who wield power do the same thing, the situation becomes very sad. Messianism is also an element of ancient culture. No one should consider himself a messiah. No one can instantly rescue the entire nation. We know that it took a very long time for Moses to guide his people across the desert, although he was blessed with direct contact with the Lord. I don’t think that our politicians have this contact, so they would be better off listening to earthly, competent individuals.

BEING LOVED BY THE MASSES IS NO PANACEA

You said in an interview with our newspaper, prior to the third round of the presidential elections, that big hopes mean a great deal of disillusionment. However, polls show that the new government still enjoys the public’s confidence and trust credit is getting bigger.

Holovakha: I hope there will be no disillusionment. Like any regular Ukrainian citizen, I wish the new government the best of success in all its positive undertakings. However, the task of every intellectual here, all those who claim to be experts, is not in bitterly saying something like “We told you so!” afterward, but in making every effort to help this government avoid further mistakes that are fraught with fatal consequences for this society. If this government follows the path of trial and error, as well as unrestrained populism, meaning, above all, that they assert themselves as the new and best rulers, replacing everything and everybody who cooperated with the previous regime, displaying an indifferent attitude to those who are determining the current level of this society, then the number of those who will be offended by such an attitude will reach critical mass. In other words, this government will suffer precisely like the previous regime.

I should also point out that the current government has surpassed the admissible quota-the number of those with hurt feelings-during this short period. Of course, there are always people with hurt feelings after a change in government, but their numbers can be kept moderate or allowed to increase very quickly. Note that they began by hurting the feelings of the creative and scientific intelligentsia, a very bad option. These people are an active component of the population. When their number reaches critical mass, the regime will have instantly transformed itself from being the national favorite to outcast. The moods of the masses are changeable. Being loved by the masses today may easily turn into mass hatred tomorrow. Not coincidentally, all great tyrants have compared the masses to women. Now she is deep in love with you, but tomorrow she will hate you with equal passion. Being loved by the masses cannot be a panacea for the current government. Leonid Kuchma was also loved by everyone in the first couple of months of his presidency. When this government finds itself disliked, much to its own surprise, there will be two options: (a) to act like Lukashenko, tightening the screws, and (b) to leave everything the way it is. In the latter case, this government would learn lots of interesting things about itself. They are aware of the possibility and are taking offence. All things considered, the government must realize that it will never be backed by journalists or intellectuals; none of these will become their partners. Rather, they will form an intellectual opposition, tracking the government’s mistakes. At the same time, I see this other option as the only correct road for the current government to show constructive progress. To make the process painless, the government must be aware of its shortcomings and incompetence; it must know that it has the right to make mistakes.

However, the current government doesn’t acknowledge its errors. Given this approach, a witch-hunt usually begins, precisely what we are witnessing. The government justifies its controversial statements about re-privatization by saying that they have been incorrectly interpreted. As for “interpretations,” there is an interesting example involving Interior Minister Yuriy Lutsenko, who said recently that he would give the militia one month to be loved by the Ukrainian public. Trying to imagine a militia officer struggling to be loved that way within a month, as ordered from upstairs, is hair-raising; it’s vulgar and perfectly idiotic. If the new government feeds off such messianic feelings, with a sense of its angelic nature and belief in its correctness, it is doomed. If it becomes aware of its own inadequacy and realizes that it can be compensated by a dialogue with those forces in this society that are called upon to monitor the process, then this government may perhaps make fewer mistakes and enjoy some good prospects. It’s also important for this society to understand that mistakes are inevitable on the part of any government, especially the current young one. Let me refer once again to mythological consciousness. There is a very large stratum of people who continue to believe that perfection is possible. The sooner our society rids itself of this complex, the more chances this government will have to achieve a positive result.