The dead arise, for justice true

Taras Shevchenko

(Abstract from The Dream, translated by Constantine Andrusyshen and Watson Kirckonnell(c))

I learned about the Holodomor of 1933 from my parents, and I myself witnessed what happened in 1947. Today there are those among us who deny the very fact of the Bolshevik-engineered genocide of the Ukrainians; you all know what their party is called. Yet even decent people sometimes tend to think about the Holodomor only in terms of past history gone forever with our forebears. But it is not gone.

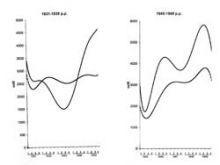

The December 2001 census shows unhealed demographic wounds on the body of Ukraine. Those who were born in an evil hour, whose questionnaires will turn yellow over time in the heaps of census documentation, speak for themselves and for their dead and unborn contemporaries. I have taken two regions for the purpose of comparison: Cherkasy oblast, where people experienced all the horrors of Soviet totalitarianism, and Rivne oblast, which, luckily, joined the “indissoluble union” only in the fall of 1939. Birth dates in questionnaires make it possible to determine how many of those born one or two years before the Holodomor, the year of the famine, and during the two years thereafter, lived to see the 2001 census.

A look at Rivne oblast shows that its vital statistics, as represented by the dotted line in the graph, are quite stable: no major fluctuations are connected with 1933. Residents of Cherkasy oblast, the homeland of our national bard Taras Shevchenko, met a different fate. The region’s vital statistics were at their lowest during the second and third quarters of 1933, when goosefoot was already lush, but potatoes and rye were still months away. Children died en masse, often with their mothers. Only in early 1935 did the birthrate in Cherkasy oblast reach the level of 1931 and somewhat exceed it toward the end of 1935. However, only women who survived the Holodomor and widows who remarried were able to give birth. Demographic losses could not be offset in a matter of years, and this circumstance reveals another disgraceful page in Bolshevik history. By this I mean the fate of demography in Ukraine.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, the study of the natural movement of population, causes of death, and life expectancy was among the most fruitful directions in the work of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, and its Demographic Institute had won international recognition. However, the January 1937 census revealed the atrocious consequences of the Holodomor. Pursuant to a September 1937 government decree, the census results were annulled, while demographers were dismissed, deported to concentration camps, or executed. “Life has become better; life has become more fun,” according to the infamous slogan coined by the bloodstained despot in the Kremlin at the height of the famine.

My personal demographic studies began in the early summer of 1947, when our neighbor, old Vasylenko, was eating the seed-buds of pear and apple trees, water seeping out of the hunger-swollen and cracked calves on his legs. Having survived the war, he could not endure the victorious times. Cats went missing in our part of the village. Nobody knew for sure, but everyone suspected a local Tatar, a chimney sweep, who was always black, but not from soot but from poverty and the burden that came with a horde of children. He reportedly lured cats with mice that he caught in the granary. That summer I shot up suddenly, catching up on the growth delayed by the war. Although our family was not starving by the standards of those days, I never had a full stomach one single day. We had artichokes growing densely along the fence. I yanked up those tubers and ate them. Incidentally, while it is a calorie bomb, artichoke is the key to the successful dietary treatment of diabetes and obesity.

The demographic picture of 1945-1949 has certain specific attributes connected to the end of the war, an event that is invariably accompanied by a soaring birth rate or “baby boom,” as the Americans have dubbed their demographic surge. The latter half of 1946 shows signs of a demographic revival in Cherkasy oblast. This revival occurred on a lesser scale in Rivne oblast, because although the war had ended there, hostilities involving the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, known as UPA, were still ongoing. In the summer of 1947 the population curve dipped noticeably and only at the cusp of 1948-1949 significantly exceeded the level of the victorious year. Almost devoid of collective farms, Rivne oblast was practically unaffected by the new Holodomor, yet its population increased on a lesser scale, not in the least part due to the deportation to Asia of the UPA fighters known as Banderivtsi [named after Stepan Bandera, the distinguished leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-OUN]. I continued my demographic studies in the late 1950s in Kazakhstan in the capacity of a doctor tending to Western Ukrainians and Chechens in my district.

So why do I respect UPA fighters? I respect them because they fought for a Ukraine free from Bolsheviks and manmade Holodomor famines. Excuse the banality, but the UPA fought for a European vector of Ukraine’s development. Glory to the heroes!