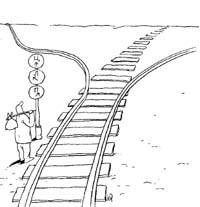

A noted regional leader appointed as premier, the regional elite mounting pressure on the national policy as a number of resourceful, well provided for, and consolidated political communities once again bring the center- region problem into the limelight.

The relationships between the center and the regions, between the regional and the capital’s elite, conflicts and tensions within the regional elite (between those appointed by the center and elected by the local elite) are, of course, a rather informative aspect of Ukrainian independence, setting the political tone of the first democratic decade. Suppose we make a little digression in history, bearing in mind the above reference points.

As the Soviet Union fell apart, Ukraine did not have a full-fledged “center” (meaning political power), it was just taking shape. At the time Ukraine actually did not have a central government, central elite, effective democratic institutions or democratic operators (political parties, civil movements, nongovernmental organizations) capable of generating a common national policy and serving as a reliable basis of a democratic political regime. Characteristically, albeit paradoxically, that “central vacuum” and lack of a strong central elite combined with the surviving administrative-command system with various Soviet and semi-Soviet verticals of power, with the central authorities cutting a lot of ice.

While getting to be independent and democratic, the center (those wielding power, the government machine) took shape and was reinforced by numerous “migrating” regional political groups, individuals, leaders, etc. One could single out several regional cadre waves that had, by the 1990s, silted the Ukrainian ruling class stratum.

The first wave was aimed at the political center in Kyiv, primarily parliament, bringing national democratic forces from the western territories of Ukraine. Such migration and “mixed marriages” with the capital’s party nomenklatura begot the first informal coalition of national democrats and post-communist nomenklatura which would last till the end of the 1990s in different versions and “residual” modifications.

The second wave originated from the displeasure of the regional “resource” elite (primarily in the eastern territories) with their representation and influence in the power structures and what they believed was a shift toward “nationalism” under President Leonid Kravchuk (1991-93). Backed up by the eastern Ukrainian “director lobby” (markedly influential in the early and mid-1990s), the sizable Dnipropetrovsk cohort marched onto the big political arena, with Leonid Kuchma becoming Prime Minister in October 1992 and elected President in 1994, accompanied by the future Premier Valery Pustovoitenko (1997-99), and a number of currently well-known politicians. Actually it was then the influential regional groups plunged into a fight for central administrative, political, and business positions.

1993 saw the first breakthrough of the Donetsk regional group. On the wave-crest of miners’ strikes, threatening President Kravchuk with rebellion, the Donetsk “miners’” lobby made Yukhym Zviahilsky Premier. After Kuchma was elected President and Pavlo Lazarenko was appointed Premier, the center was swept under the second wave of “Dnipropetrovsk colonization” (e.g., Yulia Tymoshenko, Serhiy Tyhypko, Viktor Pinchuk, et al.)

The cadre vacuum helped form a new type of elite: people of the “great leap,” making quick head-spinning careers. A number of spectacular and odious regional political and business figures emerged on the central political arena.

By the end of the 1990s, Ukraine’s executive and legislative political center had largely taken shape, along with the political class, stemming from several big cadre migrations and business and political elite rotations originating from wealthy and resourceful regions and sectors.

The parliamentary (1998) and presidential (1999) elections completed the formation of the current political regime and institutions of the authoritarian center. Laws were enacted, lending legal and institutional shape to the interrelationships between the center and the regions. Probably the last regional cadre wave providing access to the executive and legislative structures was the Donetsk group’s effective performance during the last parliamentary elections. Now parliament had two influential and numerically strong factions, so it was only natural that they should have their man in the Premier’s seat.

This brief historical retrospection has important aspects allowing one to understand the actual quality of the current Ukrainian foreign policy and the role played there by the regional groups of influence serving their and political and economic elite interests. These specific aspects are as follows:

Despite the presence of over a hundred political parties and factions in parliament (currently getting increasingly like “friendly societies of fellow countrymen”), the nucleus of the Ukrainian political class is made up of an alliance of the central and provincial elite backed up by the “resource” regions, elbowing out purely party activists and leaders, pushing them to the periphery of the elite structure. Possibly, the role of the “resource” clans and regional elite as apolitical or rather, prepolitical forces will lower, making way for public and nationwide political agents, only with the strengthening of the so-called capital’s group rooted in SDPU (U), a party that is not affiliated to any of the regions but is trying to operate in the nationwide administrative and party-ideological format; also in conjunction with the transition to a parliamentary-presidential republic.

Considering the specific role of the regions and regional elite, let us assume that the Ukrainian polity has not as yet reached the national state level. Proceeding from the notions such as state as a system, state as an empire, state as a nation, a would-be state, and so on, the current political system of Ukraine could be described as a state made up of so many regions; here the interrelationship between the center and the key regions is the backbone function, not so much from the point of view of the territorial unity of the nation as, and primarily so, in the sense of the organization of power. Such “regional” polities differ from the national states, first, in that the central government is strongly dependent on both local self-government authorities and the regional elite; second, here one can see a reciprocal conversion of resources and political influence between the regional center and the one wielding central power; third, the polity’s territorial basis does not rest upon a single nationwide cultural and political platform, but acts proceeding from administrative pressures and acts of regional sabotage, from a given alignment of forces and influences on the part of regional centers and groups; from the sum total of regional identities and local patriotism. The said identities and patriotism are actively cultivated by the regional elite to strengthen the autonomous vertical from within and often contrary to the administrative vertical, securing their legitimacy and reinforcing their positions in haggling over deals with the center proper.

Ukraine is taking shape as a political nation now, faced with critical realities, with a new post-transitory elite emerging on the political arena, all those people thinking in nationwide and party- ideological terms, having won their electorate’s confidence during the 2002 elections. Its political maturation will be complete only when representative democratic institutions take a firm root in Ukrainian soil, complimented by institutionally strong and ideologically oriented parties, nongovernmental and volunteer organizations and associations with a powerful nongovernmental sector, market-oriented media, and an impartial judicial system.

Now about conspicuously lobby-type politicking. Using the Soviet dissidents’ formula, tertium non datur, one must reckon with the existence of two vertical supports of the post-Soviet political regime. The first is the presidential administrative-command vertical with the head of state at the top, made up of presidential appointees, heads of regional and district [state] administrations, administrative and controlling authorities, military and security ministries and agencies. With their aid the regions, local self-government authorities, territorial communities, etc., are kept under constant administrative, cadre, and law enforcement control. Hence (1) considerable restrictions of actual powers vested in local self-government, (2) unconditional dominance of local administrators appointed by the center who, jointly with the local law enforcement authorities also appointed by the center and secret police, got the local resources under control and wielded power securing them a dominant stand with regard to the local elective elite. In a number of regions, such unconditional dominance gave rise to regional patriotism and regional “papism” (with regional leaders posing as “popes” ruling regional “resource” communities). By consolidating the regional upper echelons, using administrative and financial resources, a number of regional groups and leaders made the most of their outward “loyalty” to the center proper. This paid off nice especially when the central elite was gripped by yet another crisis, during election campaigns, etc. Political analysts describe it as “forcefully rental administrative capitalism.” It is a political and economic model which is important in comprehending the essence of Ukrainian politics.

Hence the second, fiscal-budget-taxation vertical permeating the political-economic and inner-elite relationships. The crisis-ridden post-Soviet economy is still largely dependent on privileged access to the allocation of national resources, budget funds, seeking rent and ways to bypass taxes. “Budgetary socialism” is a phenomenon inherent in post-Soviet capitalism. It is an upended budget- taxation pyramid serving the benefit of the central government and cultivating a low financial autonomy of the regions. It stimulates the regional elite’s corresponding strategy. Keeping loyal to the center in return for additional subsidies, exclusive access to the “summits” and lobbyism within the central executive and representative bodies of authority, squeezing out fringe benefits and a most favored status for certain business entities, working out rent-and influence-seeking political projects, looking for additional arguments in trading loyalties with the center. The process received an additional impetus when the Ukrainian economy experienced a conjunctural growth in 2001-02, accompanied by the emergence of the so-called growth regions (“rental regions” would be more like it) with the local elite focusing on reinforcing its business and political positions, using export returns and support from the populace, as well as on a number of party projects during the 2002 parliamentary elections.

All this triggers off regional instability, inner wars for resources, reducing the political process to “resource” coalitions and opposition alliances, rather than enhance the representative democratic institutions, generating a nationwide development strategy. The crisis of the post-Soviet transitory “resource-reallocation” elite raises the question of the administrative-territorial [political division] reform, optimal regional representation, tax and interbudget reforms that would give a powerful impetus to the autonomy of the local self-government authorities and lower-level forms of democracy. A solution to the stockpiling problems lies in the center-region interrelationship, not in the notorious proposal to set up a regional house of parliament or institute elective governors of the regions. There is a strategic solution: a deep-going democratic reform with a dual objective: modernizing the political system through the formation of a parliamentary cabinet and representative government, strengthening the institutions of party democracy, gaining the crucial status of public political forces. At the regional level, it is the priority of municipal development tasks, vesting the local democratic institutions and the local elective elite with real authority.