A little-known period of teaching in a village school

CHERKASY — In the life of Vasyl Stus there are two months in 1959 that are usually overlooked by researchers of his creative legacy, and thus they remain unknown to the general public.

“Longing for the real Ukraine (not Donetsk) Ukraine, he went to teach in the Kirovohrad area, not far from Haivoron. There his heart felt warmer and he freed himself of his hermit-like student existence...” His first poems appeared in print at that time — in 1959.” (From Vasyl Stus’s autobiographical sketch “A Couple of Words to the Reader,” Kyiv, 1969.)

Haivoron raion is the territory of former Haisyn County in Kamianets- Podilsky Gubernia, later Kirovohrad oblast (Vasyl Stus was born in Haisyn raion, Vinnytsia oblast). Stus, a 21-year-old graduate of Donetsk Pedagogical Institute, came to the village of Tauzhne to teach Ukrainian language and literature at a local seven-grade school.

Liubov Savchuk, a retired English teacher at a secondary school in Zavallia, and Liudmyla Maievska (Denysiuk), a former elementary school teacher in Salkiv, cherish their memories of Vasyl Stus. Both were fortunate enough to know him when he taught in Tauzhne for two months. Stus taught at the seven-grade school, and he and the two women spent their leisure together. This was a brief but extremely memorable acquaintance. Did Vasyl remember the girls? He did. He wrote letters from the army, long letters with lyrical digressions. None has been preserved. A single postcard with a stamp bearing the postmark “Lubny” and First-of-May greetings reminds Liubov Savchuk of that time: a Polish postcard with chrysanthemums and the text written in Stus’s neat hand: “Dear Liuba, Happy First of May. May this beautiful spring bring you happiness. 26.04.60. Vasyl.”

TWO POEMS

Liubov Savchuk keeps a brown leather-bound notebook that she holds sacred because Vasyl Stus filled the first couple of its pages with his poetry: two poems entitled “The Impulse” and “Resignation.” Under the last line of the first one is an inscription in Stus’s bold hand: “Written on 15.10.58, as a souvenir for Liubov Matviivna. V. Stus.”

“The Impulse” would be included in his first collection of poems Zymovi dereva (Winter Trees). It was published abroad, not in Ukraine, and the 34- year-old Stus would be condemned as a malicious enemy of the Soviet government for his poems and honest public stand as a human rights activist.

“The Impulse” also starts the posthumous collection entitled Doroha boliu (The Road of Pain) that was lovingly compiled by Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska. This book was awarded the Taras Shevchenko State Prize in 1991. However, in the final version of “The Impulse,” which is included without a title in Doroha boliu, one verse that was recorded by Stus in Savchuk’s notebook is missing:

Where people are joyously restless and not indifferent,

To whom sorrows remain unknown

Those that ruffle the feather grass in the steppe

And ring in their arms of ancient steel...

The second page of the notebook contains the autograph of “Resignation”:

Things we desire — draw near,

Things we have lost — call out!

May their fleeting memories

Touch my brow, my face, my lips!

What was the young Vasyl thinking on that evening in 1959 when he addressed his first two poems to his colleague? Ahead of him lay his service in the army, where poetry “was hardly written,” but at this very time his first poems would be published in Literaturna hazeta (today: Literaturna Ukraina) with Andrii Malyshko wishing him Godspeed:

“I believe that the creativity of the 21-year-old teacher Vasyl Stus from Vinnytsia oblast contains the seeds of good poetry. I mean particularly his original approach to various phenomena in our life and his ability to sum up lyrical reflections instead of talking about them in general. In his work, ideas and poetic images often exist as an organic, unified whole; his poetic form is clear-cut and expressive. A good command of the language determines the cultural level of this young and gifted writer. This is not empty praise; it is meant to help the young author Vasyl Stus see his shortcomings, mature faster, and shape his significant talent. In one of his poems he writes, ‘Do not stop loving your early fear...’ We hope that he will always retain this ‘early fear’ and never lose it in his poetic work and life.

“Good luck to you, young poet!

Andrii Malyshko.”

LIUBOV SAVCHUK RECALLS

“In October or maybe November 1969 a KGB officer visited the school in Zavallia where I was working. He wanted information about Vasyl Stus, what kind of a person he was, how he treated his colleagues and pupils. What could I say? I have the best memories of Vasyl. Yes, he wrote poems, but nothing nationalistic, slanderous, or anti-Soviet. He also spoke beautiful Ukrainian. Well, what kind of Ukrainian language teacher are you if you do not have a perfect command of it? Liudmyla and I tried to emulate his linguistic knowledge. We were often amazed by his use of Ukrainian words that we didn’t know. The representative of the organs left without any compromising information.”

How do you remember Vasyl Stus in that far-off year of 1959?

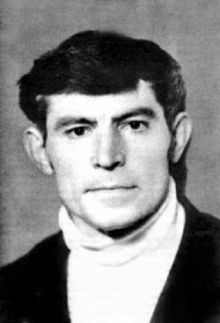

“I can still see him clearly: young, lean, tall. An attractive intellectual from the people,” she said musingly. “I am generally not a sociable type, but Vasyl and I were quickly on a first-name basis. The teacher Liudmyla Denysiuk, Yulia Kovalska, the Young Pioneer organizer at our school, Kuzma Tsymbalysty, the military training instructor in Tauzhne, and I spent our free time together. Our club was being renovated, so we went to the other side of the village and gathered near Liudmyla Koval’s house. Vasyl didn’t dance, so he either stood on the sidelines, watching us dance, or went to the library. Vasyl liked our pond and dam framed by willow trees. He loved to look at them from the yard of the house owned by Polina Fedorchuk (Smilianets), from whom he rented a room.

“After reading the publications about Vasyl Stus, it is hard for me to add anything new. Also, we knew each other for only two months. But I should note that at the time Vasyl was a cheerful young fellow with a keen sense of humor. He knew how to laugh. I think that he tended to raise his left eyebrow when he was talking to people.”

Did you know right away that your colleague Stus was writing poetry?

“Yes, but Vasyl didn’t advertise this. He gave me his notebook with poems so that I could give him my opinion. I liked his lyrical poems, but some I simply didn’t understand because they had a philosophical, symbolic content. I told him this once and he gave me an indulgent smile.”

Can you tell me about his last day in Haivoron raion?

“Before he left for the army, we threw a little party at the home of the young couple Ivan and Halyna Pohribny (Ivan is dead now, and Halyna is somewhere in Kirovohrad). It was Halyna’s idea and almost all of Vasyl’s colleagues attended; this was proof that Vasyl’s friendly attitude was appreciated by the teaching staff. Afterwards Vasyl’s landlady Polina and her husband Mykhailo Fedorchuk prepared a farewell supper, where only Liudmyla and I were present, no other colleagues; then we saw him off to the railway station.”

There is a black mourning ribbon on the grave of the Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus, which was burned by those who hate him. The inscription reads: “From Liuba and Liuda.” These girls of his youth, together with the authors of this article, came to pay homage to it in Sector 33 at Baikove Cemetery. The blossoms of pasque flowers from the slopes overlooking the Buh River in Haivoron raion bowed low over his grave.

Birch sap mixed with tears in the spring of 1990.