The repressive system, of which the GULAG was the embodiment, was intended to punish and reeducate those who dared resist the Soviet regime. A lot of Ukrainian women also shared the destiny of political prisoners. Ukrainian Women in the GULAG: to Survive Means to Win is the first historical and anthropological research into the life of Ukrainian female political prisoners in Soviet concentration camps. This book is a monograph by the Ukrainian academic Oksana KIS, which came out in early September and was launched on September 15 as part of the Forum of Publishers at Kopalni Kavy at 2 p.m.

The study is based on reminiscences of the female political inmates at GULAG camps and prisons, mostly in the 1940s and 1950s, including memoirs, letters, and oral eyewitness evidence. On the whole, the book includes reminiscences of 120 women. Most of them came from the western Ukrainian regions and were part, one way or another, of the national underground, cooperating with the OUN and UPA or just supporting the national liberation movement. The book also contains testimony of the women of other nationalities (Poles, Russians, Jews, and Germans) who focused on Ukrainian women in their reminiscences.

A considerable part of the book is fragments of and quotations from the reminiscences of former convicts. “This was done to let those women speak. By this book, I tried to give them a chance to be heard by a broader audience,” the authoress points out.

Ms. Kis emphasizes that her book is intended not only for academics and historians, but also for the general public. The authoress received the bulk of the funds for publishing the book as a small grant of the Fulbright academic exchanges program under which she once did advanced studies in the US. The Heinrich Boell Foundation also supported financially the book printing on condition that a part of the print run will be handed over free of charge to public libraries so that a wider range of readers could have access to it.

Still, what did Ukrainian women think of what was happening to them? What helped them survive in the inhuman conditions and overcome the most critical difficulties of captivity? We interviewed Oksana Kis about the destiny of Ukrainian women in the GULAG.

We know very little so far about the everyday life of GULAG prisoners, although this touched upon almost every Ukrainian family. In what conditions did the imprisoned Ukrainian women live?

“The ban on researching and discussing political repressions was lifted in the 1990s. This subject has quite often surfaced and been discussed in the media, albeit in very general outlines. It has almost never come to specifics, although former political prisoners recalled the awful conditions in prison camps, when they were practically between life and death.

“Today, research by Russian academics, based on archival materials, allows us to reconstruct and understand the way the GULAG system looked as a state institution, while personal reminiscences add a human dimension – through the experience of convicts. It is one thing how this is presented in the official documents of the GULAG structure itself and another thing how the survived eyewitnesses describe this.

“A hard 12-hour workday was a customary thing for all the GULAG prisoners, including women. The provision for an 8-hour rest was not observed in practice. This rest was often reduced to a few hours in unacceptable conditions at overcrowded, cold, stuffy, and often dirty barracks. GULAG standards prescribed two square meters of living floor area for each convict, but in practice it was often 1-1.5 square meters.

“Total insanitariness reigned supreme in the barracks, for there were no conditions at all for personal hygiene. Accordingly, this carried all kinds of diseases. In the early 1940s, when all of the Soviet economy was geared towards the war effort, political prisoners were by far the most oppressed social group in the USSR. Terrible diseases, such as dystrophy, pellagra, tuberculosis, typhoid, etc., spread among convicts on a mass scale. They were in fact doomed to death, for they did not receive enough food, clothes, footwear, and medical care.

“Clothing did not fit the climate. Women recall that their boots, made from coarse cotton-padded pants to which car tire rubber was wired, used to freeze through. The whole thing would get totally wet and freeze to the foot, so they had sometimes to rip it off together with the skin. Frostbites were a very common thing. Obviously, it was next to impossible to stay at least a little well in these awful conditions.”

“THEY WENT ON FIGHTING AGAINST THE SOVIET SYSTEM BY VIOLATING THE GULAG REGULATIONS”

In what did the Ukrainian women differ from the other GULAG convicts, such as Poles, Baltic nationals, Russians?

“In their reminiscences, women of various ethnicities rather often emphasize that Ukrainian women would remain aloof. But it is a characteristic feature of both Nazi and GULAG concentration camps. Prisoners usually rallied and formed sort of communities on the basis of nationality or ethnicity.

“Many ex-prisoners point out that Ukrainian women were distinguished by trying hard to make their everyday life as close to normal as possible – to wash, clean up, and even smarten up their barracks. The lessons those women learned in the childhood about how a housewife should keep her dwelling neat prompted them to try to turn this ersatz home into a true home.

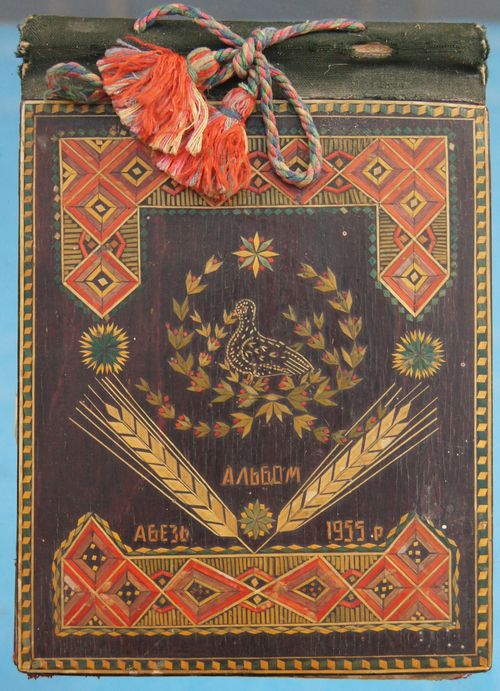

PRISON CAMP ALBUM OF O. DIAKOVSKA, MORDOVIA

“In my view, barracks performed the function of home in the psychological sense, for it was a place where women could feel more or less free and form their collective privacy. Here they could discuss the topics banned in the camp and do such strictly prohibited things as singing, embroidering, reciting literary works, and even teaching each other foreign languages. A barrack was the place where overseers exercised the least supervision. They were locked up at night, although there were humiliating searches from time to time – they could all be suddenly roused in the dead of night, stripped naked, and frisked in search of banned things. But, in any case, it is in the barrack that women were more or less free to do what they wanted to.”

What about the national awareness of Ukrainian women in captivity? Did it become more pronounced?

“It is no accident that I chose the 1940s and the 1950s as an object of my research. On the one hand, most of the reminiscences of female political prisoners refer to this very period of Stalin’s era. On the other hand, it is important that the share of Ukrainians in general and women in particular among GULAG prisoners rapidly grew in the postwar years. This period seems to be the most indicative for studying the experience of Ukrainian female political prisoners.

“The women held in the camps at that time were serving long terms (10 to 25 years). They were mostly young women and girls from Western Ukraine, who had belonged, one way or another, to the nationalist underground. Their national awareness and political views were, obviously, fundamentally oppositional to Soviet power. This essentially distinguishes this group of political prisoners from female political prisoners in other periods.

“Once in the GULAG, they immediately perceived Soviet power as hostile and occupational. In the camps, they associated themselves as a group that resists the system. They considered it their goal not to let the system break them and, thus, to defeat it. They went on fighting against the Soviet system by way of minor, but frequent and mass-scale, violations of GULAG regulations. For them, to hold out and not to surrender meant to continue the struggle.”

The isolated prisoners could not keep their fingers on the pulse of life in the rest of society. Did they manage to receive at least some news?

“One of the ways to break somebody was to isolate them in terms of information. The feeling of hopelessness and alienation undermines the psyche and forces one to lose confidence. This is why women often emphasize in their reminiscences that the sensation of uncertainty was very painful to them. They knew nothing about their relatives and fellow fighters. They knew nothing at all about what was going on in the country.

“This is why it cost a lot of effort to reestablish contact with the world. Some prisoners were forbidden to correspond at all, some were allowed to send two letters a year and receive as many as they could. But, obviously, all this correspondence was carefully checked for any undesirable content. And a prisoner could be stripped of even this minimal opportunity to correspond for a violation of regulations. As the women recall, this was an extremely painful punishment for them, perhaps even worse than deprivation of meals.

“In addition, prisoners were trying to establish some kind of clandestine correspondence and drop a line or two to their relatives. They sought any opportunity to send a letter at any cost. Most often, they would find sympathizers among the camps’ civilian employees, sometimes among the guards, and sometimes among passers-by on the street, when they were escorted to work on foot. The women gratefully recall the rare manifestations of sympathy and humanness, although they were considered traitors of the fatherland and enemies of the people in the Soviet system. But there still occurred sympathetic people who were not afraid to pick up a letter thrown into the crowd, stick on a stamp, and send it to the indicated address.”

What was stronger – faith or fear? What role did religion and prayer play for the imprisoned Ukrainian women?

“Most of the imprisoned women came from the western region, where the faithful Christian population prevails. They had a very strong Christian identity. The women in camps needed to practice their religiousness – to pray and appeal to God. This can be partly explained by their desperate situation. Under the most adverse circumstances, there was nobody to rely upon except for God and the Holy Virgin. Many of them remember praying fervently for those taken for interrogation or those who were seriously ill.

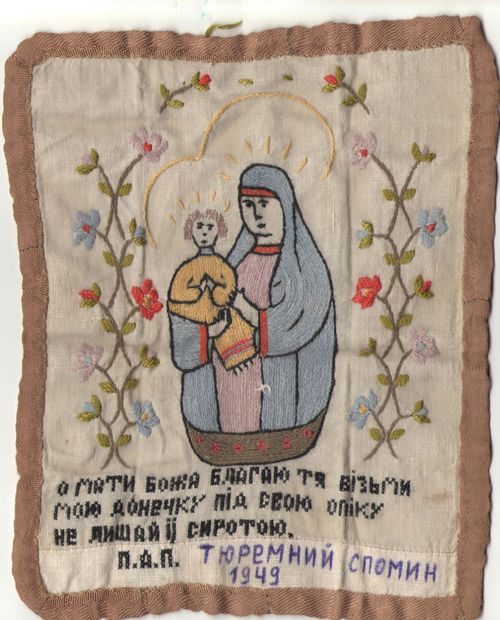

“There was also a need for religious rituals, although this was strictly prohibited in the GULAG. The women managed to make thin ropes from rye bread and little crosses from toothbrushes and embroider little icons on some scraps of cloth, to which they prayed as if it were a genuine church image. They conducted group prayers on Sundays and improvised liturgies on major feasts. The women themselves performed the liturgical roles of the priest and the deacon, which is absolutely ruled out for women in customary life. In those conditions, their need in the Divine Service was stronger than principles of the church canon.”

“CREATIVE WORK BROUGHT PSYCHOLOGICAL RELIEF TO WOMEN”

What else did women fill the spiritual void with?

“Creative work. This struck me perhaps the most in the women’s reminiscences. It suddenly turned out in those inhuman conditions which were supposed to kill everything human in people, reducing them to the level of animal instincts, that those women could have a surge of creativity. They had a need for things beautiful. There were absolutely incredible manifestations of creativity. Even the women who had never seemed to have a knack for poetry suddenly began to compose poems or songs. Almost everybody embroidered. Incidentally, not only women, but also men did the embroidering, which is totally untypical in ordinary life. The Lviv Museum of Liberation Struggle in Ukraine displays some marvelous examples of both feminine and masculine embroidery.

PRISON EMBROIDERIES OF HANNA PROTSKIV-LIVEN, 1949

“Creative work even in such primitive forms allowed them to get a psychological relief and somewhat distract themselves from the terrible realities they had found themselves in. While poetry enabled them to show emotions and dream, embroidery performed, in my view, a different function. Prison camp embroidery is not a shirt at all but a small piece of cloth on which little pale flowers, angels, crosses, etc. are stitched up. This little serviette was becoming a symbol of the community, a sign of belonging to your circle. They were usually not made for oneself – they were intended to be presented to a friend, which thus tagged the milieu of your own. Embroidery in captivity is both a creativity that allows one to psychologically endure super-hard conditions and a social function that enables one to brace up and show his or her solidarity.

Humanness, femininity… How did the Ukrainian women manage to preserve these traits?

“As, a repressive institution, the GULAG aimed to destroy the personality of a prisoner and turn an individual into an obedient builder of communism. If one defied this kind of treatment, he or she had only one way out – to the next world. So the goal of a political prisoner, who wanted to remain an integrative personality, was to preserve the original system of values, moral guidelines, and social norms. For women, it was important to remain feminine. Reminiscences show that the Ukrainian women were trying to keep their gender identity intact and remain women by means of the routine everyday female practices.

“Prisoners had their names replaced by numbers. It is one of the methods of dehumanization. The female prisoner who has a number no longer has a gender. The baggy, colorless, and coarse clothes also lacked any signs of femininity. Yet the Ukrainian women made efforts to alter their clothes which had they often taken off the prisoners of war or even the killed. They were trying to make these clothes fit their figures. They would re-stitch, re-cut, and adorn their garment, sewing some primitive lace onto it. Of course, they looked miserable, for they were exhausted with backbreaking work, inhuman conditions, starvation, and diseases. But many former prisoners, both male and female, point out in their reminiscences that women were more successful in trying to keep themselves smart. They degraded physically and morally not as fast as men did.”

What is the most tabooed topic in the reminiscences of former female prisoners?

“It’s not difficult to guess. We can come very rarely across any mention of the female body and sexuality in the women’s reminiscences. Occasionally, they speak about a crippled, exhausted, dirty, and sick body – the result of interrogations and captivity. The women speak more seldom about such sexual abuse as forced exposure during interrogations and searches or voyeurism, when overseers peeped at women in the bathroom.

“But they speak extremely seldom about sexual violence which, as is known from other sources, was very widespread in prison camps. Obviously, many Ukrainian women fell victim to rape (no female prisoners were secure against this!), but we will find practically nothing about it in their reminiscences. Silence is the result of a very severe trauma, the feeling of shame and pain, and a certain fear of incomprehension and stigmatization. Incidentally, victims of rape in ordinary life also keep silent about this for quite a long time for fear of being accused of a ‘wrong’ and ‘provocative’ behavior.

“Conversely, reminiscences of male political prisoners say that female inmates were raped en masse by criminal prisoners with the connivance of overseers. The latter also abused their power and access to resources in order to buy the female body for a piece of bread. Forced prostitution for the sake of survival is a phenomenon that existed in many crisis situations: during the Holodomor, on the Nazi-occupied territories, and in German concentration camps.”

“WOMEN WERE TRYING TO CREATE A LITTLE OASIS OF HUMANNESS IN THOSE BEASTLY CONDITIONS”

Male and female prisoners were kept separately and were not allowed to come into contact. In all probability, they sometimes managed to dodge the ban. Did the GULAG hold a place for such relationships with men as friendship and love?

“Oddly enough, it did, even though the GULAG administration was taking stern measures in the postwar period to separate men and women. In spite of a separate detention, it was impossible to completely isolate them because there was a need for men to work in the women’s areas and vice versa. Prisoners of both genders could also make contact at the production facilities, where they were used as workforce. Paradoxically, the number of the women who became pregnant and gave birth was not reduced much after the measure had been taken to separate prisoners of different sexes.

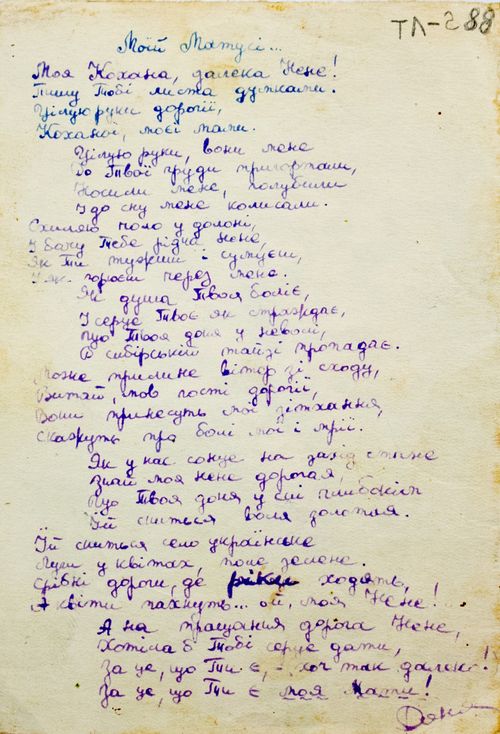

A PROTEST POEM ON A PRISON CAMP LEAFLET

“In addition to stories about undesirable relationships (sexual violence), the women’s reminiscences also include instances of a close friendship that grew into love in the course of time. After the release, this love could even be followed by a marriage between the inmates kept in different camps.

“Men and women corresponded by means of ‘camp mail’ – a clandestine system of circulating notes and letters among the prisoners. They could communicate in this way for a long time, sharing their innermost thoughts. Sometimes, a man or a woman, who had never seen each other, waited each other for years after they were freed.”

Maternity behind bars: was it a blessing or a curse?

“Some women who were sentenced to serve long terms (20-25 years) were aware that they might never go out of this camp, so they could make a deliberate decision to give birth to a baby in captivity. The women strove to have somebody whom they could give their love and care, creating a little oasis of humanness in those beastly conditions.

“When it was a rape or forced prostitution, the resulting maternity was hardly a source of joy.

“For other women, who became pregnant in detention or were convicted with a baby in arms, this was a true tragedy because their newborn or imprisoned children could not remain with them too long. Babies aged 1 to 2 were sent to Soviet orphanages. In some instances, if the prisoner’s relatives were actively taking up the case with all kinds of authorities, the child was referred to their care. This gave at least a slim chance to see the child again in the future. But for many women, their children were lost forever somewhere in Soviet orphanages.

“For some, maternity was a salvation and a chance to perform their human female function, but for others, it was pain and tragedy. However, a lot of researchers point out that the decision to bear a child, as well as many other, lesser, violations of camp regulations, was in fact a way for a woman stripped of all rights to make at least some decision on her own and to be aware of being able to exercise at least some control in her life.”

“CARING FOR ONE ANOTHER, WOMEN COULD SURVIVE MORE EFFECTIVELY TOGETHER”

You noted that women degraded not so fast as men did. Why?

“Indeed, the evidence of this comes from both men and woman, so I am not inclined to doubt the fact that women managed to remain less affected physically and psychologically by the conditions they were in. We should take into account a number of factors here. One of them is purely physiological. Women need less food in their everyday life. Their body is less consumptive, so a limited food ration is not so dramatic for them. Besides, the female body contains more fat deposits and, hence, can hold out longer when the ration is abruptly reduced, using its inner resources. Besides, owing to the particularities of gender socialization, women have more knowledge and skills to organize their everyday life and maintain sanitary conditions. Keeping things in order, they have somewhat improved their perception of reality. In my opinion, women managed to keep their bodies and psyche in an acceptable condition longer just because they could care better about themselves (clothes, dwelling, and hygiene).

“Also important is the so-called ethics of concern. Women are taught from an early age to be concerned about others. As a result, concern becomes one of the pivotal functions in the structure of women’s gender identity, and they performed it, caring for their fellow-sufferers in prison camps. Caring for one another, women could survive more effectively together. Researchers of Nazi death camps have also noticed a similar phenomenon: women formed stauncher and more efficient groups of mutual help, while men were more often engaged in conflicts and confrontations.

“Women also often mention the importance of mutual psychological assistance. Sooner or later, almost every female prisoner would fall into despair, get disappointed, and sometimes want to commit suicide, but her friends calmed, comforted, and persuaded her to live on. It is also about the tradition of ‘women’s chat,’ when they share their worries, thoughts, and concerns in everyday life. In those critical conditions, this had a psychotherapeutic effect of ‘talking out the sorrow,’ which allowed women to share the emotional strain and not to lose heart. A person who lost heart and gave up struggle stood, as a rule, no chances to leave the GULAG.

“In general, this book is not about the GULAG but about the way Ukrainian female prisoners lived in it. We are used to portraying female political prisoners as powerless victims of a totalitarian regime and describing their existence in the categories of suffering, humiliation, and brutalization in prison camps. But this view does not allow one to see these women as people who refused to obey the system and went on resisting the regime by the very fact of their existence. My book is in fact about the invisible feminine capacity, about the female strategies of adaptation, survival, and resistance to the ruinous impact of prison camps on the personality of female prisoners. According to reminiscences of the former female prisoners, Ukrainian women did not feel themselves as powerless and helpless victims who passively accepted their fate. Not at all! On the contrary, they sought and found ways to preserve at least some physical and mental health by supporting each other. Contrary to bans, they rallied into communities, forming a ‘Ukrainian diaspora’ of sorts in the camps. They sang, drew, wrote poems, embroidered, prayed, marked holidays, loved and bore children… Far from all managed to survive, but those who succeeded in overcoming the regime are testifying against it. This book is about a victory over death and the womanly face of this victory.”