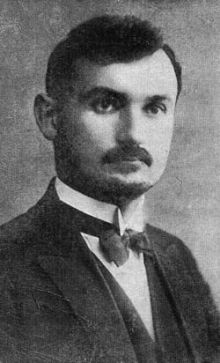

Arsen Richynsky was born 115 years ago, on June 12, 1892 (Old Style; New Style: June 25). Although the anniversary of his birth is not a round figure this year, it is still an occasion to remember him.

Richynsky’s name has been unjustifiably forgotten in Ukraine. He was a physician/specialist as well as a philosopher, historian of religion, culture, and art, composer of religious music, and folklorist. He was very active in civic life and campaigned for an independent Ukrainian state and an independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Because of his wide-ranging activities Richynsky suffered lifelong persecution and eventually gave his life to this cause.

This list of accomplishments would seem more than sufficient reason for honoring his name. But Ukrainians are a strange people. We tend to commemorate Bolshevik monsters and erect monuments to characters like Zhukov, Catherine II, and others rather than pay tribute to genuine Ukrainian patriots.

Richynsky did much to establish independent Ukrainian Orthodoxy. In the period between the two world wars he was an activist in the movement for the Ukrainization of the Orthodox Church in Volyn. He published a number of works in which he sought to defend the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. His book Problems of Ukrainian Religious Consciousness remains topical today. Moreover, Richynsky’s legacy is a giving a boost to the issue of instituting an independent Local Orthodox Church in Ukraine.

Richynsky lived an eventful life. He was born in Tetylkivtsi, a village in Kremenets district of Volyn gubernia (today this village is part of Shumske raion in Ternopil oblast). His father Vasyl was a local Orthodox parish priest.

Although all Orthodox clergymen were supposed to promote the idea of “autocracy, Orthodoxy, and nationality,” in other words, Russification, in Volyn they had to reckon with a powerful Ukrainian culture, and in most cases they identified with it.

On the one hand, the life of the Volyn clergy determined Richynsky’s interest in folk culture, which would later manifest itself in his scholarly works and cultural endeavors. On the other hand, it also led to the formation of Richynsky’s national identity. As the son of a priest, he was naturally interested in religious life. Although he chose a secular career, he was versed in church rites and dogma, and was especially interested in folk church culture.

After completing primary school in his village, he studied in the Klevan theological school and the gymnasium in Kremenets. Eventually, at his father’s insistence, he enrolled in the theological seminary in Zhytomyr.

Zhytomyr was the administrative center of Volyn gubernia, with a vibrant cultural life and various cultural communities, including the Society of Volyn Researchers. Its members published scholarly anthologies and devoted considerable attention to the work of enlightenment, often inviting seminary students to their meetings. It is possible that Richynsky began taking a special interest in Ukrainian history and literature in Zhytomyr.

After completing his studies at the seminary, Richynsky enrolled in Warsaw University’s medical school, but with the outbreak of World War I he was evacuated. In the spring of 1917 he passed the state exams at the University of Kyiv and was assigned to the district hospital in Iziaslav, where he worked until March 1920. During this period Richynsky was actively involved in public life. He organized concerts, staged plays, and published books. He also edited the periodical Novi dorohy (New Roads). According to his daughter Liudmyla Richynska, he published the journal Izaslavskaia doroha (The Iziaslav Road) and was a regular lecturer on Ukrainian studies for schoolteachers in the neighboring town of Ostroh.

During this period civic and cultural life in Volyn underwent Ukrainization. Schools with instruction in Ukrainian and Ukrainian-language publications appeared, and Ukrainian became the official language. Richynsky was involved in this process. Unfortunately, Ukrainization did not attain its logical completion. The Ukrainian government was replaced by the Bolshevik and Polish regimes. Under the Peace Treaty of Riga concluded between Russia and Poland (1921), Volyn was divided between these countries.

Iziaslav found itself under Bolshevik rule. Shortly before this happened, in the spring of 1920 Richynsky left for Trostianets, a village in Lutsk district that had been annexed to Poland.

Richynsky worked in Trostianets until 1922. Here he married Nina, the daughter of a local priest, Pavlo Prokopovych, but his life was not tranquil. Someone denounced him to the authorities and he was arrested. He was released thanks to his wife’s dedicated efforts.

After moving to Volodymyr-Volynsky in 1922, Richynsky was appointed chief physician of the city hospital and retained this post until August 1925. That year he was arrested a second time on what boiled down to charges of conducting pro-Ukrainian activities, but no incriminating evidence was ever found and he was soon released from prison.

Naturally, with such a politically unreliable background there was no sense in Richynsky remaining in government service. He had education and experience and could earn enough for himself and his family as an independent medical practitioner, which he did until 1939. His high professional qualifications and excellent reputation ensured him a large number of patients and made him relatively independent financially. In the interwar years there were only two Ukrainians, including Richynsky, among the seventeen medical practitioners in Volodymyr-Volynsky.

During his medical career Richynsky’s public activities never ceased. Beginning in 1924, he financed an “independent monthly of the Ukrainian church renascence” entitled Na varti (On Guard). This periodical existed for 10 years, although for certain reasons he was forced to change the title to Nashe bratstvo (Our Brotherhood) and later, Nasha tserkva (Our Church). Richynsky organized his own publishing company in the editorial offices of the periodical, which specialized in the problems of the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

In 1925 Richynsky compiled a collection of popular church songs for village choirs, entitled Vsenarodni spivy v ukrainskii tserkvi (National Songs in the Ukrainian Church). According to the author, its goal was to ease the “services in church in the Ukrainian language and demonstrate the superiority and beauty of the Divine Service conducted in the mother tongue.” With time his other collections, such as Ukrainska vidprava vechirnia ta rannia (Ukrainian Vespers and Matins), Ukrainski koliadky (Ukrainian Carols), and Skorbna maty (Our Sorrowful Mother, a collection of songs from the Bohohlasnyk, a religious songbook). Richynsky believed that the true religious spirit lay in the folk church culture, with music being an important component. He broached this subject in his book Problems of Ukrainian Religious Consciousness.

Richynsky belonged to a number of Ukrainian civic and political organizations. He was a member of Volodymyr-Volynsky’s Prosvita and Ridna khata (Native Home) societies. Under his guidance branches of Plast, the Ukrainian scouting organization, were organized in Volodymyr-Volynsky and throughout Volyn. With his help his wife Nina organized a branch of the Union of Ukrainian Women. He also took part in the cooperative movement. Toward the end of 1929 Richynsky joined the legal organization, Ukrainian Volyn Association. Approximately at this time he became a member of the underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), but his main field of endeavor remained the Ukrainization of the Orthodox Church in Volyn. On his initiative, a congress of Orthodox laymen was held in Lutsk in 1927, which came out in support of the Ukrainization of Orthodoxy. In 1933 Richynsky and his associates organized a large rally in Pochaiv, where this matter was also raised.

In the second half of the 1920s and the early 1930s Richynsky published a number of articles on church issues in the Ukrainian press, as well as a series of booklets on the subject: The Origins of the Episcopate: In Connection with Questions Pertaining to the Grace of the Hierarchy of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (Volodymyr-Volynsky, 1926), A Critical View on the Resolution of the Holy Synod Banning the Ukrainian Church Congress (Warsaw, 1927), The Contemporary State of the Church and Religious Life of the Ukrainian Population in Poland (Warsaw, 1927), Two Plebiscites in Volyn on the Language of Divine Services (Volodymyr, 1927), and My Response to the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church in Poland (1929).

His booklet For Happiness, Glory, and Liberty! — which analyzed the system of Plast education — was published in Lviv in 1930. He published several works dealing with problems related to his profession: Several Remarks on the Biological Meaning of the World, The Unity of Nature, and People’s Spirits after Death. All this is proof of Richynsky’s diversified interests and his truly encyclopedic knowledge.

At this time he began working on Problems of Ukrainian Religious Consciousness. He is believed that he began writing this book in 1929 and completed it in 1933. It is both a deep-reaching theological treatise and brilliant cultural study. The first two chapters were published in 1930-31 in the Lviv-based Literaturno-naukovyi visnyk (Literary and Scientific Herald). In 1932 he published the booklet Na manivtsiakh (Wrong Paths) in Volodymyr-Volynsky, in which he raised a number of issues related to the problems highlighted in his book.

In the foreword to Problems, Richynsky offers the following justification of the topical nature of his book: “A book on religious issues at a time when atheism is being promulgated on a massive scale is either totally irrelevant or very timely. An analysis of the Ukrainian folk world outlook proves that the absence of religion is an artificial phenomenon and alien to the folk world view. It is a symptom of spiritual captivity, which is dangerous to the very existence of the nation. Spiritual independence, the creation of our own national religious ideology always adds to the people’s confidence in their strength, dignity, their belief in being on the right side and in their future. In contrast, the subservient acceptance of alien ideas and views undermines the people’s spiritual strength and resistance, lures them into worshipping foreign idols. After that comes the death of the people.”

In fact, Richynsky proposed (although not in so many words) his own version of a national religious ideology for Ukrainians. To an extent he was influenced by Viacheslav Lypynsky’s historical and philosophical views. This influence is especially noticeable when he writes about Ukraine being “torn” between East and West. Richynsky offered his own original method of bridging that gap: by creating a synthetic national religious ideology that would unite both Eastern and Western traditions. As he writes in the foreword, “This author has arrived at the conclusion that a synthesis of the great religious cultures of East and West is that vein, that main direction of Ukrainian religious life.”

The heavily censored book was printed in Ternopil, although Volodymyr-Volynsky is considered the place of publication. The author was also aware that he had not succeeded in doing everything the way he had planned. Indeed, the book lacks a clear expository manner; some chapters are theoretical while others are practically oriented. There are eight chapters in all: “Saint Sophia of Kyiv,” about the emergence of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church; “The Historical and Canonical Causes of the Ukrainian Church and National Revolution,” in which he argues that the emergence of the UAOC was due to historical and canonical reasons; “The Peculiarities of the Ukrainian Religious Character,” mostly about the maturation of Ukrainian religious consciousness; “The Christian Age,” about the evolution of Ukrainian religious consciousness during Christian times; “The Specific Features of the Russians’ Religious World Outlook”; “The Road to Calvary,” about the distinctions in the Ukrainian and Russian religious characters; “The Church and Nationalism,” and “The Status of Ukrainian Synthetic Idealism.”

Despite the book’s considerable chronological remoteness and certain shortcomings, Problems of Ukrainian Religious Consciousness is still topical today. A number of highly regarded Ukrainian scholars believe that it is one of the best — if not the best — works in the field of Ukrainian religious studies. The author’s erudition deserves special notice. He has a firm grasp of biblical and specifically religious and religious-philosophical texts, works by German classical and Russian religious philosophers, Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, and Czech literary classics, and scholarly works from various spheres of knowledge. Last but not least, his medical knowledge proved to be quite instrumental in the writing of this book. Although not immediately noticeable, this knowledge helped him understand important problems. This blend of medicine and philosophy, although not typical of European culture, was often encountered in the medieval Islamic world.

Unfortunately, Problems had a small print run in 1933, and when the Soviets occupied Volyn a number of copies were destroyed. Today the 1933 edition is a bibliographic rarity. Thus, Richynsky’s views on religious matters remained a terra incognita. It was only after it was reissued in 2000 and 2002 (also as small print runs) that contemporary researchers were finally able to familiarize themselves with Richynsky’s legacy of religious studies.

Needless to say, Richynsky’s activities were duly noted by the Polish authorities, and he was closely watched by Polish punitive-repressive organs. Undercover agents, who had penetrated his closest milieu, reported on his every move to their superiors. On a list of OUN activists, drawn up by the Volodymyr-Volynsky district secret police department in 1934, Richynsky’s name figures at the very top.

He was repeatedly arrested and spent some time in the notorious concentration camp of Bereza Kartuzka, where he was first sent in 1935.

Richynsky was imprisoned in Bereza Kartuzka a second time in May 1939. He was released only in September, after the Second World War began and western Poland was occupied by the Germans and eastern Poland, by the Soviets. The Polish prison guards deserted their posts and the inmates escaped. On Sept. 16 Richynsky arrived in Volodymyr-Volynsky, but before long he was arrested by the NKVD because of his civic activism and contacts with the OUN. He spent several years in jail without trial. Finally, on May 5, 1942, a special council of the NKVD USSR sentenced Richynsky to 10 years’ imprisonment.

Richynsky’s wife and two daughters were also repressed. At the time his eldest daughter Myroslava was 15 years old and the younger one, 6 weeks.

Richynsky served his term in Uktlag from where he corresponded with his family and even sent poems to his daughters. Unfortunately, none of his letters have survived. In 1949 Richynsky was released, but before being freed he was attacked by criminal inmates, who stabbed him seven times — such was the “fine tradition” of the Soviet labor camps, where the camp administration would deliberately set the criminal convicts against the political prisoners. Richynsky survived, but the authorities did not allow him to return to Ukraine. He was forced to live in Kazalinsk, a town in Kazakhstan, where he worked as a physician. Even in those conditions, which were far from ideal, Richynsky found time for his scholarly work. In 1952-53 his medical articles were carried by the Russian-language periodical Zdorovie Kazakhstana (Health in Kazakhstan).

Richynsky died of a hemorrhage on April 13, 1956, and was buried in the graveyard of the Dzhusali railway station in Kizil- Ordinsk oblast.

Arsen Richynsky was not destined to carry out many of his plans. His period of imprisonment under the Poles and lengthy imprisonment in the GULAG took a heavy toll on his health and prevented him from working normally. One can only try to imagine how much he would have achieved had he lived in different times. To date, his works have still not been collected and studied.

Professor Petro Kraliuk teaches at Ostroh Academy National University