The scandals and rifts in the ruling team, witnessed by this country last week, marked not only the beginning of a political crisis but also changes in a number of principles, guidelines, and the functional model of the current Ukrainian government. They have also essentially altered the political terrain before the parliamentary elections. These are the conclusions of Ukraine’s leading political scientists, who gathered at the Russian Media Center to share their ideas about the causes and consequences of the change in the Ukrainian government. In addition, the experts tried to prognosticate the main intrigues as well as the course and outcome of the parliamentary elections. Through the media they conveyed a number of “useful recommendations” for both the participants of the conflict and the political forces that are only acting as passive onlookers.

CHOOSING BETWEEN “YUSHCHISM” AND “PARTYISM”

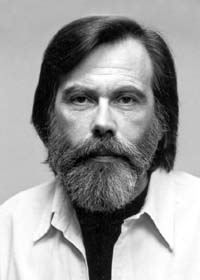

Vadym KARASIOV, director, Institute of Global Strategies:

There was a binary model of power, now we’ll have a binary model of elections. But it won’t be along the Yushchenko-Yanukovych lines, but the Tymoshenko-Yushchenko lines. The whole intrigue and drama of the election campaign will be focused on the struggle between these two leaders and the two trends of the Maidan (Maidan revolutionaries and Maidan evolutionists). The rest of the campaign participants are extras, political forces that will have to join this main group.

After Prime Minister Tymoshenko’s dismissal, Kuchma’s model of presidency, which relied primarily on administrative gears, ceased to exist. Given Tymoshenko’s independent participation in the parliamentary campaign, the current government’s election project — e.g., setting up a trilateral bloc — has also ended. If this trilateral bloc were implemented, this would spell victory for the ruling authorities within the government’s structure over the party, since it would be a party of power whose task would be to participate rather than compete in the election campaign, thus confirming the 2004 president’s mandate and being a kind of additional presidential election. Yulia Tymoshenko’s dismissal and the collapse of the Orange team mean that everyone will be taking part in the campaign independently. Moreover, they will be rivals.

The party of power, which will be the party only of the president, will have to compete and struggle not just for seats in parliament, but also to confirm the president’s 2004 mandate. Hence, the president’s dilemma in the aftermath of the cabinet’s resignation: how to change the structure of government, which is practically split, degraded, and diffusive. On the one hand, banking on the evolutionists and professionals, including those from the previous government, is proof that the president is trying to form a coalition within the framework of the administrative and new business elites. I would describe this trend as Yushchism: restoring certain Kuchmist mechanisms of power. On the other hand, there is a party project that will be coordinated by Roman Bezsmertny, in which emphasis will be on the party resource (e.g., party-affiliated president, the party, participation in the elections, seats in parliament, and participation in the formation of governments). Obviously, the president’s strategy now, in the conditions of a governmental crisis, will balance between Yushchism (enlisting pragmatic elites from the previous political regime) and partyism (relying on one’s own political party). To this end, a given party is faced with a problem; there are no leaders, no faces, except for the president. And so, if the president wants his party to top the campaign winners list and to be able to take an active part in the formation of a cabinet coalition, he must start campaigning now — in other words, he must dedicate himself completely to the elections. This will be a rather difficult step for the president to take because until now he has stayed above the process, above the state; he wanted to rule rather than manage. Now he will have to manage, participate in, and stay at the head of this state rather than above it.

“CONFLICTS IN THE OFFING”

Volodymyr MALYNKOVYCH, director, Ukrainian Branch, International Institute for Humanitarian and Political Studies:

Our president is acting contrary to the constitution; he has appointed Yekhanurov as acting prime minister, but he is not a member of the cabinet. Article 15 of the Constitution of Ukraine reads that only a member of cabinet can remain in office before a new government is appointed. I think the current political situation has become considerably more interesting. Among other things, it has sharpened public interest — and this facilitates the development of a civil society. Many people now have to choose between two favorites. Therefore, they will have to consider things other than good looks.

Yulia Tymoshenko stands a fair chance of leading the coming campaign — provided she has the media resource. She didn’t cut an impressive figure as prime minister, but she can emotionally influence the general public better than all our politicians. In this sense Viktor Yushchenko is weaker, as in many other respects.

Also, during her televised interview Yulia Tymoshenko made a very good move by joining the orange and blue ribbons, thereby demonstrating that for her the road to the east of Ukraine is open, on the one hand, and on the other hand, that she is prepared to seek a coalition if and when the Orange or the Blue campaigners win the 2006 elections. In fact, siding with the Blues appears even more convenient for her, since throughout the campaign there will likely be furious competition between the “Orange people” and Yulia Tymoshenko, along with a pitched confrontation between radicals and moderates. The big question is the third force. We see two forces today: the former government and the current one. However, in order to strengthen their team, the Orange people must find someone to top the roster. They have no one whose ratings are even close to Tymoshenko’s. Most likely, they will try Lytvyn whose personal ratings are very high, but this will trigger a conflict already in the new Orange composition. And so I predict that this will not be the end, and that there are conflicts in the offing.

The Blue people have a very vague image, specifically Viktor Yanukovych. In order to be a serious candidate in the parliamentary campaign, they must change their strategy, tactics, and image. Then, after winning, e.g., 15 or even 25 percent of the vote, they might well keep Yulia Tymoshenko company in the new government that will be formed after 2006.

“POLITICS REDUCED TO A SQUARING OF ACCOUNTS”

Andriy YERMOLAYEV, director, Sofiya Social Study Center:

This crisis had been expected by voters, citizens, experts — everyone. No one knew how it would come to pass, but it was clear that the new government was controversial, and that sooner or later they would start playing the “Who’s better?” game, especially since the situation was aggravated by severe economic conflicts.

On the one hand, once the dust clears, we will have to admit that there was actually nothing special about the events in the past few days. All revolutions — left- or right-oriented — are known to have ended with pragmatists coming to power. Chernomyrdin replacing Gaidar in Russia, in the early 1990s, is a good example. What makes Ukraine special in this sense is that here the radicals were expected to become reformers. Then it transpired that they were state-building socialists, with unsystematic approaches and a good deal of utopianism.

Incidentally, one of the problems confronting Ukraine is a foreign one, not a domestic one. The rest of the world is showing a great deal of disillusionment about the events in Ukraine. Politicians and experts in the West are astonished: why did the government, with such wonderful carte blanche for quick and dynamic changes, indulge in populism, build up its electoral muscles, and end up squandering everything?

There are major internal problems, the primary one being that consciousness has falling prey to authoritarianism. Remarkably, half a year ago sociologists and journalists were talking about the growing ratings of confidence. In reality, it meant increasing confidence in conditions of increasing belief. This rating was not supported by concrete institutional actions. The result was a growing demand for an authoritarian kind of politician, rather an able political administrator. The people want a leader who is capable of resolving problems among the Blue, Orange, and Red supporters. This is horrible because it means the creation of a demand for simple solutions, an ordinary kind of politician, an ordinary kind of ruler. This is the product of the revolutionaries’ activities.

Another problem is the crisis of legitimacy, which is connected not only with the people’s declining confidence in the current government but primarily with new economic processes.

The third problem is that we are in a unique situation where none of the subjects of the new conflict has a program of action or an alternative. In fact, our politics are being reduced to the squaring of accounts, to a kind of psychological retaliation. “Great! They’ve failed!” The rhetorical question is, “What will happen to the election agenda, and what is supposed to be accomplished in the first place?”

My prognosis for the election is that the ruling party will most likely become consolidated. Our Ukraine will have to work long and hard to convince Volodymyr Lytvyn to join the NPU bloc. This bloc may expect to collect 25 percent of the vote at best. If this bloc is not formed, and if Lytvyn takes part in the campaign as an independent force (most likely as part of a bloc), the outcome will be gruesome for all concerned. The ruling party, based on Our Ukraine, will collect 20 percent at best, but most likely 16-18 percent. In a crisis, Lytvyn’s bloc may expect 10 percent. For Yanukovych, 12-14 percent would be the happiest achievement, whereas they can actually expect to get some 10 percent; CPU is likely to collect between 7 and 10 percent. The Socialists have lost all their dividends, including their image as a “moral force.” They can count on 5-6 percent. PSPU’s Derzhava, which is an interesting and aggressive project, may surmount the eligibility barrier. Leonid Kravchuk’s ambition is praiseworthy, and I think they can get over the barrier, but that’s all. All told, this project is technical and is likely to be used as a breach to form a future anti-presidential coalition, say, in a Kravchuk-Yanukovych-bloc format, also possibly the BYuT.

What’s the problem with our electoral architecture? The main one is that no one can form a majority. The constitutional reform will take effect on January 1. What does this mean? My prognosis is that there will be a second parliamentary election in fall 2006. There will be different players in the game. The main agents will be Tymoshenko’s bloc against Lytvyn’s. If so, 2007 may well see an early presidential election.

I have several brief recommendations, namely that the Orange people should avoid direct confrontation with Yulia Tymoshenko. They would feel better opposing the Blues and Reds, but fighting Tymoshenko would practically mean self-destruction. And so it’s time to ponder technical projects, powerful and serious ones that are capable of transferring the Tymoshenko intrigue to themselves.

STAGFLATION TRAP

Volodymyr FESENKO, chairman of the board, Penta Applied Political Study Center:

Regrettably, there were reasons for dismissing the cabinet, considering its performance. The first and most serious reason was that Ukraine had found itself trapped by stagflation, due to an unbalanced socioeconomic policy. At the same time, what we have now is a decline in industrial output and a higher inflation rate. This is generally called stagflation. It’s a very serious problem. In this sense Yulia Tymoshenko left her post as prime minister in a very timely fashion, without having to answer for the results of her socioeconomic policy.

As for the new government, Yekhanurov’s prime ministership is not as simple a task as meets the eye. If one were to count the votes of those who support Yekhanurov as prime minister (Our Ukraine, perhaps Lytvyn’s NPU, and the SPU, UNP, NRU, PPPU), the sum total is 167 votes. Obviously, this is not enough. At the same time, those who will surely vote against (CPU, BYuT, SDPU (U), and perhaps PRP) will produce 132 votes. Another 127 votes are left, those of the so-called “swamp” in which most of the votes are held by the Party of the Regions. The number of parliamentarians who are not aligned with any factions is also significant. Yekhanurov’s confirmation as prime minister will depend on them. In view of this, it is extremely important for Yushchenko to secure an indirect expansion of the propresidential coalition in the Verkhovna Rada. This will not be a majority in the classical meaning of the word. In my opinion, however, the “stability memorandum” is the first step on the road to forming a coalition of indirect expansion.

As for the pre-election landscape, I do not agree with the formula of the binary model of future elections. However, I agree that the main counteraction during the elections will be between the political forces supporting Yushchenko and those supporting Tymoshenko. But there will be three favorites during the elections. The third favorite is the Party of the Regions, or the Yanukovych bloc. Despite all of Yanukovych’s ambiguity and obvious weakness, his replacement as leader will result in the Party of the Regions losing at least half of its supporters. The thing is that Yanukovych has become a symbolic leader since the presidential elections. He has lost the capital of real leadership in the eyes of the political elite in the east and in the Donbas, yet in the eyes of a rather large part of the electorate he remains the symbolic leader of the east. I think that the Party of the Regions, or Yanukovych’s bloc, will collect at least 15 percent of the vote in the coming elections.

As for the two favorites, the problem here is that Yushchenko must form a bloc. It may include NRU and Lytvyn’s People’s Party of Ukraine. The struggle for the PRP will continue, although even now it is apparent that all or part of the PRP will side with Tymoshenko. Yet if the NSNU decides to go to the elections separately, they will end up being completely destroyed because after the recent events it is being regarded as a party from Yushchenko’s circles, which has been accused of corruption. Society will not ascertain whether or not these accusations can be confirmed; it simply believes them. It believes them a priori because no government is immune to corruption. In that case, since there is the problem of compensation of leaders, it is necessary to separate the bad leaders from the good ones. It is necessary to find the bad guys, who will bear the responsibility for the government’s bad performance.

Another important issue for the NSNU is the number-one spot on the list. If it is not the president, then who will it be? I will risk voicing this hypothesis: they will try to talk Lutsenko into it, since only Lutsenko can beat the resource of the anticorruption politicians, who are making every effort to use Tymoshenko and Zinchenko as their most effective weapons. There is, however, a principal aspect. A dangerous precedent may arise when the heads of power structures take part in the elections on the strength of party rosters. Turchynov is retired, which is good from this point of view. The next question concerns Lutsenko. In the very near future he must publicly declare that he will take part in the elections as a politician (which means that he will have to vacate his post as minister of the interior within several months), or that he will not take part in the elections.

Yevhen KOPATKO, Donetsk Information and Analysis Center:

We carried out a poll four days before the crisis. It showed that 61 percent of Ukrainians believe that there was an economic crisis unfolding in Ukraine. It is also possible to assume that both Yushchenko and Tymoshenko have passed the peak of their political popularity. By definition they will never have ratings higher than the ones they had this summer, especially in view of all these conflictual situations. The current government is offering countless reasons for criticism. This is creating a field for the opposition’s work.

IT TURNS OUT THAT NO ONE NEEDED TYMOSHENKO

Mykhailo POHREBYNSKY, director, Kyiv Center for Political Research and Conflict Studies:

This government, and primarily Yulia Tymo shenko, had no subject, except the people, upon which she could rely, neither within nor outside this country. This is another important aspect that predetermined her fate. Another element is that this government was of no use to foreign subjects. No matter how hard Ukraine has been trying to be a subject in the foreign policy domain, it remains mostly the object of other countries’ policies. Russia, in particular, has been behaving lately as though it is not interested in discussing any serious issues with Ukraine. It is coming to terms with those who are taking care of the new Ukrainian government, i.e., the Americans and Europe. In this manner they have already solved one issue, the agreement between Putin and Schroder, which is damaging to Ukraine’s interests.

As for the Tymoshenko government, neither the Americans nor Russians needed it. And they made this perfectly clear. I personally have little doubt that, in the matter of Tymoshenko’s dismissal, Yushchenko was exposed to a great deal of pressure from the US, in addition to that of the “family.” Our situation is customarily such that when the US wants something here in Ukraine, the Russians want something that is the exact opposite. Tymoshenko’s dismissal is a unique case when the interests of both these powers tallied.

Yushchenko had a wonderful opportunity, one that in theory could have been realized, to obtain a majority in the next parliament for himself and Tymoshenko, and it would have been a convincing majority. But Yushchenko has lost it. In my opinion, a majority in the next parliament may be formed even without the NSNU. This wouldn’t be bad from the point of view of the political system, for then we would smoothly switch over to the European variant, whereby the president represents one political force and the leader of the parliamentary majority represents the other one.