The creative work of writer Nikolai Gogol (Mykola Hohol, an ethnic Ukrainian) was highly acclaimed not only in Russia but also throughout Ukraine when he was still alive. Gogol was permeated with Ukraine wherever he was.

It is perhaps no accident that the contemporary connoisseurs of his works claimed, “Gogol thought in Little Russian (Ukrainian — Ed.) and immediately translated himself into Russian.” Russian literature researcher Aleksandr Pypin wrote in his History of Russian Literature: “Gogol was a Little Russian in mind and soul,” and “He had a distinctly Little Russian mindset and taste.” An equally well-known connoisseur of literature and the psychology of creative work, Dmitry Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky, wrote in 1909 about Gogol’s Russian works: “Reading them, you cannot dispel the illusion that they were translated from Ukrainian.”

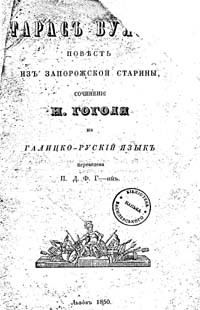

These conclusions are not at all surprising because it is common knowledge that Gogol used Ukrainian proverbs, sayings, songs, jokes, small facts of everyday life, etc., in his works. Let us take, for example, Evenings on a Farm near Dykanka, where he used 220 words of Ukrainian origin, of which 208 are listed in Ukrainian language dictionaries. There is no doubt about it: check for yourself if you don’t believe it, a very useful native language exercise. His works were the object of special attention on the eve of “jubilee” anniversaries. A similar thing occurred in 1902, when the fiftieth anniversary of the writer’s death was approaching. His alma mater, the Nezhyn Institute of History and Philology (a lyceum in the times of Gogol — Author) named after Ukrainian Prince O. A. Bezborodko, decided to duly honor the memory of their former student Gogol, organizing, among other things, an exhibition of all his works. This had been announced in good time by the press of the then Russia. To the organizers’ utter astonishment, their call was answered as early as 1902 from outside the Empire — from Lviv in what was known at the time as Austrian Galicia, from Ivan Franko, an enthusiast and connoisseur of Gogol’s works. Franko, himself an ardent bibliophile, sent a gift of the rarest nineteenth century Ukrainian-language Gogol editions published in Galicia, an unthinkable thing in Little Russia-Ukraine whose language was oppressed in letter and spirit by the Valuyev circular and Ems ukase. A real gem in Franko’s donation were the two volumes of Evenings on a Farm near Dykanka published by Mykhailo Poremba in Lviv in 1864- 1865. Yet, by far the greatest surprise and interest of exhibition visitors was evoked by Taras Bulba, a green paper-jacketed book with a fine vignette on both sides. According to the title-page date, it was published in 1850 in Lviv “in the characters of Stavropihiysk Institute.”

Some Great-Russian chauvinists would show indignation: “To think of it! They published Taras Bulba in Galicia and in the Ukrainian vernacular! Shame! Who could possibly allow this here?” The organizers had rough time. The Lviv-published Taras Bulba became a bibliographic rarity as soon as the late nineteenth century owing to its small press run, soft binding, hatred by Polish chauvinists and clerics, great interest among the Galicians, and, moreover, thanks to the Ukrainian, albeit not yet standardized, language. The book has an interesting and tragic history. Not without reason is it said, “Every book has its own fate.”

In 1958, my wife, born in Yaroslav on the other side of the river Sian, acquainted me in Kolomyia with her vuyko (maternal uncle in Galicia) Vasyl Verbenets (1891-1971), a biology teacher educated in European universities, had a command of several languages, and was considered a Ukrainian erudite and bibliophile, although he had taught biology in Polish lyceums beyond the Sian. Living in Yaroslav, he turned his hospitable house into kind of a club, where well— and not-so-well-known Ukrainian authors, artists, public figures, and politicians used to stop over en route to Krakow, Prague, Berlin, and Warsaw. And every guest considered it an honor to leave something as a keepsake — an autographed book, a note in an album or a photo, a drawing, a watercolor, or an extempore note — for the host. All the gifts made up not only a large multilingual library but also sort of a museum of twentieth century Ukrainian literature.

In 1945 Polish chauvinists drove my future wife, a young teacher, and unmarried Verbenets away from primordial Ukrainian lands almost empty-handed. The exiles finally ended up in Kolomyia, where vuyko taught biology and agronomy in a teachers college for many years. He was considered excellent at his business. Running away from Yaroslav in 1945, Vasyl hurriedly took only his documents and a few Ukrainian books presented by his close friends, while all the riches of the library and the home museum were plundered by the Poles, as he later sadly recalled. In 1946, the “gallant security officers” of Kolomyia were again “purged” private libraries of “nationalist” literature, burning it in the courtyards and arresting some of its owners.

Aunt Olha, Vasyl’s wife, hastily ripped off the top right-hand end of Taras Bulba’s title page out of fear because it bore a little seal “Museum of A. Petrushevych.” The frightened woman thought “A. Petrushevych” might have been the former president and dictator of the West Ukrainian National Republic in 1918-1919, unaware that the dictator was Yevhen, not Anton. Such was the power of fear. And the book was maimed. Anton Petrushevych was quite a well-known nineteenth century Muscophile Galician historian and the owner of a big museum of antiquities. In 1958 Vasyl Verbenets presented me, a book- lover in his opinion, the “maimed” Taras Bulba as a birthday gift. He had won the book at cards well before the war from a friend of his, writer Denys Lukiyanovych (1873- 1965), who had taught with him in Polish lyceums beyond the Sian. Lukiyanovych was related to some extent to Anton Petrushevych. Both of them knew very well about book rarities! “Our Bulba,” as Vuyko Vasyl claimed, was printed in parts from 1850 to early 1851. This can be confirmed by correspondence between Yakiv Holovatsky, a friend of Markiyan Shashkevych, and his brother Ivan.

Translating into “Galician Ruthenian” was Petro, Yakiv Holovatsky’s second brother, one of the founders of the Ukrainian theater in Galicia, a participant in the famous Congress of Ruthenian Scholars in tempestuous 1848, when all things Ukrainian were called Ruthenian. We do not know why the translator hid his first and last name under the cumbersome cryptonym of P. D. F. Hym. The well-known “dictionary of Ukrainian pseudonyms” by the late Oleksiy Dei discloses his last and first names. It is known from literature how and why Yosyp Bodiansky presented Yakiv Holovatsky in 1945 the second version of Gogol’s Taras Bulba of 1842. It is this version that Yakiv instructed his brother Petro to translate. Let us add that in his translation Petro deleted all instances of the great-power adjective Russian, replacing it with Ruthenian. The text of our book, except for the maimed title page, has been preserved very well. Also missing is the upper binding. The book was printed in the so-called maksymovychivka, the then non- standardized Ukrainian spelling. But this is a separate tale.

In 1952, toward the centenary of Gogol’s death, the USSR Academy of Sciences published the bibliographic index Gogol and Ukraine, which claims the first translation of Taras Bulba into Ukrainian was done as late as 1935 and says nothing about the Galician publication. But it is authentically known that in the 1860s-90s Galician school readers in Ukrainian literature were full of Taras Bulba in the shape of various quotations and fragments, of course, in the already improved spelling. It is Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar and Nikolai Gogol’s Taras Bulba that aroused in young hearts the sense of national identity, Cossack-type stubbornness, and resistance to all occupiers of Ukrainian soil. It is known from the correspondence of contemporaries that Galician young people could readily pick up a fight for any attempt to call Gogol a moskal (Muscovite — Ed.), a non- Ukrainian. Where is now “the spirit that led us to the battle?!” Apparently, all Bulba-related issues still await a meticulous researcher.

Having done a thorough search, bibliographers of the Vasyl Stefanyk Library in Lviv and Lviv University’s Central Research Library told us they have not a single copy of the aforesaid Taras Bulba.

The director of the latter, Candidate of Sciences in history Zinovy Yakymovych, talked us into presenting the rarity to them alone. I do so this with pleasure, for I consider Lviv State University my fourth alma mater. I failed to graduate from the three preceding ones for reasons beyond my control. I just wonder if the Nezhyn Pedagogical University also retains Ivan Franko’s gift of 1902.