“We thought at first that we were exhibiting classic masters of the Ukrainian transavantgarde, but it seems we are exhibiting classic masters of the Ukrainian transacademism instead,” director general of the National Museum of Russian Art in Kyiv Yurii Vakulenko smiled, referring to the “School of Arts” exhibition. The project was recently presented at the museum, it being the result of artists’ work within the framework of the Great Ferry residence.

STILL LIFES OUT OF NOTHINGNESS

When working on the project, the creators offered their own interpretations of etudes dealing with the main disciplines of arts education: still life (Volodymyr Budnikov), plastic anatomy (Vlada Ralko), and double nude portrait (Oleksandr Babak).

Budnikov’s paintings depict metaphysical shapes, which seem to grow out of smog and dense fog. A still life with a black square, a still life with a sphere or a black jug – these objects appear from the gray background, it seems that matter thickens slowly, and these things will assume volume and emerge out of nothingness over time. “The germs of items that are just trying to become complete things,” Budnikov described these shapes. In fact, artists build their own identity when learning, particularly from those still lifes.

TO REVITALIZE EDUCATIONAL SCHEMES

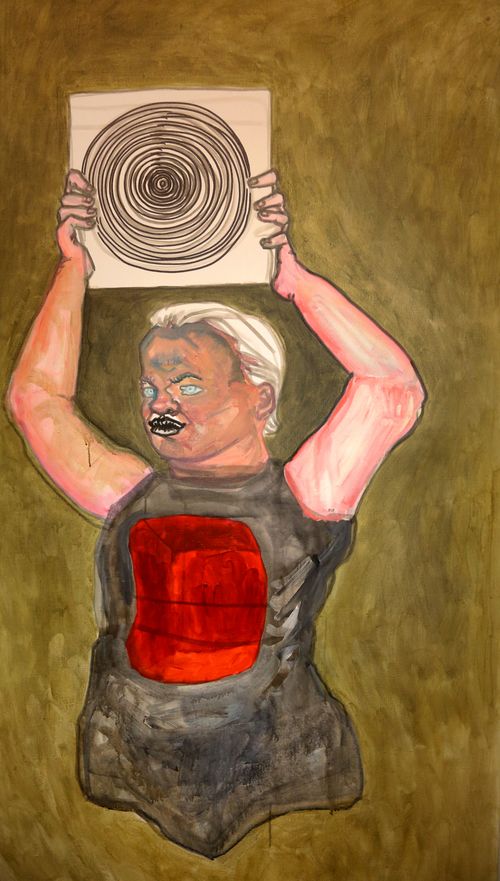

Ralko created seven paintings, which are a kind of anatomical tables. But, as the artist noted, she corrected images to make them fit her own and societal experiences and knowledge about life, death, shame, injury, illness, love, sex, and war. “I painted the subjects of anatomical tables who are astounded with the secrets of their own constitution,” Ralko said about her work’s subjects.

VOLODYMYR BUDNIKOV’S STILL LIFE WITH A BLACK SQUARE. “THE GERMS OF ITEMS THAT ARE JUST TRYING TO BECOME COMPLETE THINGS,” THE ARTIST SAID DESCRIBING THE SHAPES IN THE PAINTINGS HE CREATED FOR THIS PROJECT

The body of a man in profile shows all his organs: kidneys, stomach, intestines, an artery winding like serpentine. Various gadgets and headphones lay next to it, as if embedded in the body; these are devices, which people exploit so hard to fence themselves off from real life. The painting is called Protection. Chunky legs, but instead of a muscular torso, one sees a skeleton that stares, fascinated, at the laptop’s monitor. Probably, brain, heart and other “gear” have gone with the flow of information. This painting is called News.

Sometimes people grow similar to subjects of anatomical tables. Ralko, to the contrary, transforms schematic shapes into living people.

AN EXERCISE WITH MORALITY

The strong point of the exhibition’s last room is Babak’s monumental painting Cain and Abel. This is a double nude portrait, inspired by the Bible story, which is so frequently mentioned today in the context of relations between Ukraine and Russia. “This story has been replayed since the first people’s time,” Babak remarked. “The double nude portrait, meanwhile, is part of the arts academy’s fifth year’s program. I learned to paint it at Mykola Storozhenko’s studio. Working on double nude portrait projects allowed me not only to acquire competencies, but to fill forms with morals and content as well.”

VLADA RALKO’S TARGET. THE ARTIST TRANSFORMS SUBJECTS OF ANATOMICAL TABLES INTO LIVING PEOPLE WHO FEEL ANGER, PAIN, AND PLEASURE

The painting shows Abel defeated by his brother, just like in the Bible story. It was the first homicide, the first violent death. In the work itself, the content of the painting pushes the limits of its form. A conditional exercise becomes a work of art, grows filled with life.

A LIBERATING CAGE

Another part of the exhibition includes books, an anatomical atlas and teaching aids for artists. According to the participants of the project, the books, apart from building up the historical context, also serve as a kind of commentary on the works of the artists. Muscles, schematic shapes – such “dry” pictures teach the student to depict life.

An album catalog, which is also a work of art in some way, supplements the project. “The catalog brings to mind traditional textbooks that were published in Ukraine in the 1950s-1980s, and books of Mystetstvo Publishing House, very popular at that time,” curator of “School of Arts” project Valerii Sakharuk commented.

Therefore, exercises, which are usually done mechanically, are starting to make sense, become filled with stories. Probably it is only in this way, putting fresh feelings and thoughts in a static form, that one can become a master; in fact, this applies to any profession. “We entered training at a very tender age when we could not understand the entire system which we had to act in as artists,” Ralko mused. “Later, when studying at the academy, we had more time to analyze what we were actually doing. On the one hand, our art school was a very special institution, it was traumatic for us in a sense. On the other hand, it gave us some toolkit with which we have been able to go down our own paths. We were within a closed system, but this system gave us the key with which we could come out and act independently.”

The “School of Arts” exhibition will last at the National Museum of Russian Art in Kyiv until February 28.