Fever on the streets and a pompous cold Empire style, new privileges for the third estate and the emergence of an empire which could rival the Roman one in grandeur, although it existed for a much shorter time

The history of France 200 years ago has a lot of figures that can be easily found in today’s Ukraine. The proof of this is the exhibit “Freedom vs. Empire” now being held at the National Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko Museum of Arts. Many of the items are exhibited for the first time. The bulk of the exhibits are graphic pictures, but what attracts the greatest attention is caricature. The exposition also displays porcelain, Wedgwood plaques, and other historical items.

CONCEPT

The project’s idea came up a few years ago. Oleksandra Isaikova, a senior research associate at the museum’s graphics section, who is, together with the section head Olena Shostak, the curator of this exhibit, calls it a cultural project, when various items show a profile of a certain era or phenomenon. Besides, Isaikova confesses, the deeper the museum got absorbed in the subject, the more it understood that this closely echoes with 20th-century history and today. The story unfolds from the beginning of the 1789 French Revolution until the exile of Napoleon to the island of Saint Helena, where he died.

A “STOP IMAGE” OF THE SEIZURE OF THE BASTILLE

One of the first exhibited works is Jacques-Louis Bance’s etching “The Storming of the Bastille.” “This composition was unbelievably popular. It was repeated many times, and later artists painted pictures on the basis of this engraving. For there were no photo cameras at that time, and everything is fixed here,” Isaikova says.

French King Louis XVI seems to be looking at this scene – for an engraving by Johann von Mueller, done on the basis of the monarch’s grand portrait, hangs on the opposite wall. The museum people are saying that, as long as this image of the king was of great ideological importance, the engraver was specially invited to Paris to do a drawing. The master worked on the engraving for four years, but the work lost its importance in 1789 because the country’s political life changed radically. The engraving was first released in 1793 in Nuremberg, when the king and his wife Marie Antoinette were executed.

REDISTRIBUTING OPPORTUNITIES

“Caricature as a genre of art was finally formed in the 18th century. It is the French Revolution events that gave impetus to the development of French caricature in a situation of new freedoms and challenges,” Isaikova points out.

The key theme of the cartoons drawn in 1789-91, at the beginning of the French Revolution, is the alliance of three estates – the clergy, the nobility, and commoners. “There were still illusions of being able to achieve equality and fraternity. This is why we can see a bit idyllic pictures here,” Isaikova adds.

Here the three estates unite in a dance, and a good-natured caricature is accompanied with sentimental verses. And the next cartoon strikes a more threatening note: a third estate representative robs an embarrassed noble of his officer tunic, while a cleric looks on pensively. “Indeed, sir, I think your tunic of an officer will suit me better,” the caption says. This story dates back to the formation of the National Guard in Paris on July 14, 1789. The rank of an officer was usually a privilege of the nobility, but even a commoner could achieve a high rank in the National Guard, if he showed certain abilities and the leadership liked him. So this institution became an important symbol of fighting for the third estate’s new opportunities.

A CANNIBAL ON THE RIVERS OF BLOOD

Among the displayed caricatures of the times of Napoleon’s First Empire, the rarest are those created by royalists. Often anonymous, they were published in England, where Napoleon was not liked, and then smuggled to and distributed in France in order to undermine the emperor’s prestige.

“These sheets are from the album that belonged to Count Henryk Ilinski who had a manor near Zhytomyr,” Isaikova notes. “How they found themselves in our museum is a mystery. Anyway, there is seal on each sheet with the inscription ‘Count Henryk Ilinski’ and his personal coat of arms.”

THE ULTIMATE IN CANNIBALISM, 1815

“The Ultimate in Cannibalism,” a caricature created in 1815 by Louis Francois Charon, parodies Napoleon’s full-dress portrait by the artist Jean August Dominique Ingres. “The full-dress portrait depicts Napoleon on the throne in a mantle and with a scepter. On the caricature, he also wears a mantle but is seated on a pile of dead soldiers and, besides, on the bank of a ‘river of blood,’ as the caption says. We can see cities reduced to dust and the attacking troops. My most favorite detail is a tricolor that shows the Phrygian cap, a symbol of freedom, surrounded by chains, while the caption says: ‘Disguised as freedom, I’ve chained you,’” Isaikova comments.

Even if royalist masters did not sign, they could be easily recognized by style and content. Firstly, a right composition with a good drawing was typical of such works. A commoner could have hardly created this, while aristocratic education included art exercises. Another particularity is a huge number of captions in small print. According to Isaikova, the best examples of folk caricature comprise fewer inscriptions, for they should be understood by large masses of the illiterate populace. Thirdly, accusations against Napoleon of, say, crushing a royalist revolt usually found an echo in the old aristocracy only.

A DANCE AROUND THE TREE OF FREEDOM

“Soldiers of the French Revolutionary Army Are Erecting a Tree of Liberty in Zweibruecken on February 11, 1793” – the Ukrainian spectator will easily recognize the prototype of Kyiv’s notorious Christmas tree in this caricature by Jean Godefroy.

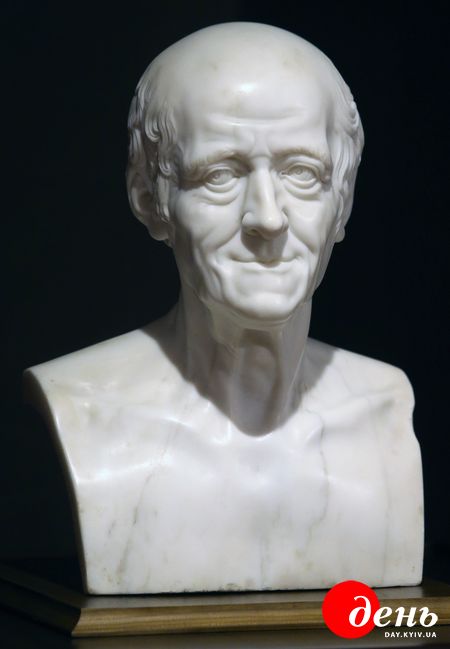

VOLTAIRE

The engraving was found this year in the museum’s repository. It depicts the French troops that are putting up a Tree of Liberty, a symbol of the French Revolution. This symbol came from the US and later spread all over the world. “The French revolutionary troops were in the habit of erecting a Tree of Liberty at every place they were coming to,” Isaikova says. “The tree on the engraving really looks like a Christmas tree, but it was usually an oak or any other tree. Sometimes it was just a stick adorned with ribbons. A Phrygian cap was put on the Liberty Tree’s top, and a celebration in honor of freedom and equality was held. It usually consisted of dances, such as carmagnole or farandole.”

GREAT VICTORIES AND DEFEATS

In the hall about the First Empire, you can see engravings that depict victories of Napoleon’s army, for example the outcome of the Battle of Austerlitz. Jean Godefroy made this engraving after Francois Gerard’s picture commissioned by Napoleon on the second day after his victory. The emperor could not help being proud of this event, for the enemy considerably outnumbered his army. As a result, the anti-French coalition broke up.

THE BATTLE OF AUSTERLITZ

The picture portrays Napoleon himself on a white horse the moment General Rapp arrives to announce the victory. In general, there are a lot of historical persons among the characters. Isaikova points at marshals Berthier and Bessieres, generals Duroc and Junot, and the captured Russian Prince Repnin-Volkonsky.

Next to the image of a great victory is the print “The Death of Prince Jozef Poniatowski during the Crossing of the Elster on October 19, 1813” by Philibert Louis Debucourt, which shows the defeat of Napoleon’s troops in the Battle of Leipzig, after which the emperor abdicated the throne. The national hero of Poland, Jozef Poniatowski, died covering the French army’s retreat.

HEALTH-FRIENDLY EMPIRE STYLE

These battle scenes are in contrast with empire-style household stuffs, such as porcelain items by French and German manufacturers, a dainty clock, and plaques. Some of them, incidentally, bear the portraits of Napoleon’s enemies: British Prime Minister William Pitt, Admiral Nelson, and Admiral Hood. Isaikova notes that the key sign of the empire style is reference to classical antiquity and military subjects. Even those who resisted Napoleon liked this style which flourished in the emperor’s hour of triumph.

PLATE. THE MANUFACTURE NATIONALE DE SEVRES, 1846

Refined vessels contrast with rather a simple desk of the architect made in the first half of the 18th century. It is a representative of the then popular folding furniture called “a la Tronchin” – after physician Theodore Tronchin who invented it.

“In particular, Tronchin healed spinal disorders architects complained about. This doctor understood that architects just sit uncomfortably at work and invented a desk at which one can work well without harming his back. The desk’s height can be adjusted by means of special legs. The angle of the desk top’s can also vary if necessary,” Isaikova says.

DEATH, CRUTCHES, AND A WHITE CAT

After the Leipzig defeat, Napoleon abdicated the throne and was exiled to the island of Elba. France saw the beginning of a short period of Restoration, when the Bourbons regained power. Closely watching the developments, Napoleon chose a favorable moment, landed in France with just a thousand of soldiers, and reaches Paris in two weeks. This signaled the so-called Hundred Days period, when Napoleon managed to stay in power again.

The caricature “The Arrival of Nicolas Buonaparte at Tuileries on March 20, 1815” shows this moment. The emperor is accompanied by the figures of Death and Poverty, and crutches are falling out of the box on which it is written “War Compensations.” It is clear from the gloomy faces of commoners and bourgeois that these people do not believe Napoleon’s promises. The most good-natured character here is a well-fed white cat in the center who says: “I have velvet paws.” This French idiom describes a person who pretends to be kind but has a selfish motive.

A TOY FINALE

After the Waterloo fiasco and the second abdication, Napoleon was banished to the island of Saint Helena, where he died. The 19th-century caricature “Thank God, the Devil Takes Him” depicts this episode metaphorically. The winner of the Battle of Waterloo, British Field Marshal Wellington, exiles Napoleon to the island of Saint Helena with the help of a diabolo, a popular toy at the time also known as Chinese yoyo. It consists of two round pieces of plastic or wood joined together, with a piece of string wound between them. You put one end of the string around your finger and make the yoyo go up and down.

A HANDKERCHIEF WITH NAPOLEON

The only exhibited item that is not part of the Khanenko Museum collection is a men’s handkerchief, “The Stage of Europe in December 1812,” made in England. The Khanenko Museum borrowed it for the exhibit from its “neighbor” – the Kyiv Picture Gallery. In the center of this quite large handkerchief is Napoleon pursued by the allegoric figures of Russia, Sweden, and Prussia. Other figures here symbolize Austria and states of the Confederation of the Rhine, a protectorate of Napoleon, and there are scenes that symbolize the emperor’s crimes, such as dispossession of the Pope.

HANDKERCHIEF “THE STAGE OF EUROPE IN DECEMBER 1812”

The texts on the handkerchief are in the English and German languages. Isaikova explains: this means that it is a replicated thing, a souvenir of sorts, which was also exported to Germany. Such handkerchiefs gained popularity in the 18th century, when tobacco came to Europe. Tobacco was not so much smoked as snuffed. Accordingly, people sneezed and had to wipe their faces. “Political themes were widespread in such household stuffs. Handkerchiefs, fans, plates and vessels could have this kind of coloring,” the exhibit co-curator adds.

***

There is one who watches all this revolutionary and military madness with a smile. It is Voltaire – the philosopher’s 19th-century marble bust stands right here. The “themes on handkerchiefs” also occur today, and history helps us understand our own selves better. So you are welcome to visit the exhibit “Freedom vs. Empire” now underway at the Khanenko Museum until November 4. Please follow announcements on the project’s Facebook page, for guided excursions and other thematic events will be held concurrently.