On the eve of Russian elections, the RF Election Committee publicized the so-called list of authorized delegates of presidential candidate Vladimir Putin. The list includes even the names of famous musicians, such as viola player Yurii Bashmet, world-renowned conductor Valerii Gergiyev, and singer Anna Netrebko. It seems that only pianist Mikhail Arkadyev wrote an article “I Blame,” where he blames Putin for “irreversible demoralization of the country and shameless felonious moral split of Russia.”

The Day started its conversation about high things with its distinguished guests, Leonid HRABOVSKY and Oleksandr SHCHETYNSKY, namely with this actual and eternal topic, relations between the power and art.

Leonid HRABOVSKY: “I fully support Arkadyev’s stand and condemn the collaborationists, whoever they are.”

Oleksandr SHCHETYNSKY: “I can only morally support Mikhail Arkadyev, an outstanding Russian pianist and conductor, whom I deeply respect as a musician, and now – as a citizen. His standpoint reminds me of what Zola and Leo Tolstoy did. As for those who were tempted by the power’s tops, this is really saddening, and we should remember: it is impossible to wash yourself from this dirt; it will stay with you forever. For they are standing no risk, unlike Shostakovich or Prokofiev, who in their time had to formally tolerate Stalin’s regime and could be free only in their creative work.”

The Day has called 2012 the Year of Sandarmokh List. Mr. Hrabovsky, the regime killed your father in 1937. What is your vision of the anti-totalitarian program for the society? Should quality music be part of it?

L.H.: “This is no simple question. I think, above all we should take care of humanization of education, because the new generation, if deprived of a corresponding level and direction of education and patriotic breeding, will hardly be able to think. On the other hand, we have a strong factor of spreading information, the Internet. Ukraine should use this instrument above all to spread the information about its history, its best times, and our cultural treasures, including the information about the Executed Renaissance. That was such a bright flash, about which the present-day generations should know as much as possible.”

O.Shch.: “As for me, I am pessimistic about this. I am worried that the artistic ambitions of the new generation are short-time only. They are not interested whether they are able to make artistic discoveries. They just want to get the ‘minimum portion’ from life.”

L.H.: “The portion of comfort.”

O.Shch.: “As a musician, I can say that music education has been destroyed in Ukraine. The professional level of musicians has colossally decreased, and it will take more than one generation to restore it. After all, we have to involve even outsiders in this work, who could create the humus we could use as groundwork in the future. But many of those who could have changed something or influence something left for the better world or emigrated, or for some reason have stopped in their development. To invite musicians from abroad we need to create corresponding conditions, not only financial. When George Crumb, Giya Kancheli, or Peteris Vasks, composers of the world scope, came to our country, nobody noticed them. No events were held with them apart from the concerts where their music was performed.”

O.Shch.: “We need to understand that present-day Ukraine is a Ruin in terms of culture, and finally start the restoration from scratch, not waiting for the state to take care of this. There is no other way out, because the state does not need our culture, at least for the present time.”

Are there any music compositions, which squeeze a slave from a man, as the saying goes?

L.H.: “Yes. Above all, this is the entire oeuvre of Johann Sebastian Bach and Gustav Mahler.”

“SPIVAKOV AND BASHMET’S CONCERTS TURN INTO GLAMOR GET-TOGETHERS”

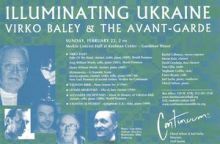

Mr. Hrabovsky, in your time you were part of a legendary group of composers, Kyiv Avant-Gardists. Tell us more about those times?

L.H.: “Several students from Borys Liatoshynsky’s composition class, namely Valentyn Sylvestrov, Vitalii Hodziatsky, Volodymyr Huba, Vitalii Patsera, and yours truly started to make themselves known and created some kind of stir, though not all at once and not at the same moment. One of the catalysts of this process was the All-Union Review of Creative Work of Young Composers and its regional tour, which took place in late 1961 in Kyiv. At that time the concerts heard several other plays which aroused some interest. Our conservatory friend, a student of conducting class Ihor Blazhkov soon became our ideological leader, who stirred our creative ideas, hence was the ‘head of the department responsible for promotion’ of the best ones. Back in 1929, when not only the Contemporary Music Association (ASM) was liquidated, but also the store ‘International Book,’ which sold the modern Western literature and scores, Blazhkov dared to make a desperate move: he began to correspond with the leading composers and music figures in the West, such as Igor Stravinsky, Paul Hindemith, Nicolas Slonimsky, and Vladimir Ussachevsky, in order to receive scores and music recordings with their help. Blazhkov was receiving an endless stream of parcels and packages and long-playing records, owing to which we got acquainted with the music of the 20th century. A symbolical event for us was getting acquainted with the textbook on dodecaphony and 12-tone system of composition. I translated the book very quickly from German into Russian. Sylvestrov, Huba, and Hodziatsky were the first who applied it in Ukraine. However, the very fact of uptaking the music aesthetics and methods, which had been declared by the Communist Party ideologists hostile to social realism, automatically ascribed us to frondeurs and dissidents, all the more so, when samples of our creative works went beyond the USSR, owing to Blazhkov, and were performed on Western radio and concerts. Other musicians started gradually to consolidate around us, including students of younger courses, specifically Volodymyr Zahortsev, Osvaldas Balakauskas, Petro Solovkin, and to certain extent Yevhen Stankovych and Ivan Karabyts (in their first attempts of composition).

“Another symbolical event for us was the chamber concert in Kyiv Philharmonic Society, which took place on December 17, 1966, and included the works by Debussy, Schoenberg, Bartok, Liatoshynsky, Sylvestrov, and Hrabovsky. The tickets were sold out right away. After the concert, unknown passers-by thanked me right in the street.”

O.Shch.: “The 20th century has much material left which has not been mastered by our musicians, it simply passed by those who were living in the Soviet Union. However, there were of course pirate editions of the works by Arnold Schoenberg and Olivier Messiaen.”

L.H.: “But there were only several editions, which gave quite a vogue notion about the composers’ creative work.

“We had an opportunity to listen to Western music until around 1966. Such performers as Philadelphia and New York orchestras came to Kyiv at that time; a ballet from Bratislava performed The Rite of Spring by Stravinsky, whereas the Parrenin Quartet from France performed Bela Bartok’s works, which nobody in the USSR had played before. But after some Kyiv official tightened the screws, all the world performers started to go to Yerevan, Tbilisi, and Kyiv was simply cut off.”

O.Shch.: “Incidentally, we still lack top-level performers who would come on tours to our country. We should understand that Spivakov and Bashmet do not have the level they used to. Their concerts turn into glamour get-togethers, which have no relation to music or art. We badly lack managers who would bring truly outstanding artistes.”

“POLAND WAS OUR WINDOW ON EUROPE”

One of the actual newspaper discussions of nowadays is the eternal topic of books which had an influence on us? What books have influenced you?

L.H.: “The books which formed my worldview, hence influenced my creative work, are My Musical Life by Rimsky-Korsakov, Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann, The Karamazov Brothers by Dostoevsky, Orgy by Lesia Ukrainka, Faust by Goethe in translations by Mykola Lukash and Boris Pasternak, Concerning the Spiritual in Art by Wassily Kandinsky, Internationalism or Russification? by Ivan Dziuba, works by Velimir Khlebnikov, especially the treatise Boards of Fate; Non-Indifferent Nature by Sergei Eisenstein, The Mastery of Gogol by Andrei Bely. Let alone Shevchenko’s Kobzar, it has been with me since childhood.

“However, not only fiction is important for composers, but also specialized literature. Since we are geographically close to Poland, many kind persons sent to us piles of scores by contemporary Polish authors: Penderecki, Lutoslawski, Serocki, Gorecki, Szefer. The specialized Polish publications, such as Ruch muzychny and books on theory, music aesthetics, specifically the almanac Res facta, have also played their role. We were able to learn about contemporary Polish music, since Poland was a socialistic country. West-German magazine Melos could be found only in several libraries in Moscow.”

O.Shch.: “My literature includes practically the whole world classical music, including musical modernism of the 20th century. At a certain period I thoroughly studied the literature of Executed Renaissance, which is also called the literature of Red Renaissance. Remarkably, Russian literature has no phenomenon of this kind; I think it has never had such a versatile and strong stream of dissent in literature. Maybe this phenomenon emerged owing to the preceding epochs of social suppressions and bans, which overlapped the development of Ukrainian culture.”

“EVERYONE IS FACING THE PROBLEM OF CHOICE NOWADAYS”

Mr. Hrabovsky, in the program “Evening with Mykola Kniazhytsky” on TVi you said that Ukraine for a while has not had any symphony or opera plenum, just song plenums. Actually this is what Shevelov said: one of the most important merits of Peter the First is that he cut Ukraine from Europe. How can we resist this primitivization?

L.H.: “Actually, I pin hopes on the new generation, because the current realities show the dominance of pop music, which follows us everywhere: in supermarkets, coffee shops, and transport. It perverts some psycholinguistic fundamentals of a personality, which enable a person to accept the beautiful things without bias. And not only in music.”

L.H.: “The history of humankind had periods which can be considered music-centric. But we are living in the time, when we cannot speak about focusing on music. However, music culture in Germany has been put on a high level and the profession of a composer is highly appreciated there. Why? Because since Beethoven and Mozart’s time practically every German family has owned a piano.”

When should young children of kindergarten age be taught quality music?

O.Shch.: “You should distinguish between real development and imitation of such education. There are pedagogues who have deeply understood this mechanism, like Russian-German pedagogue Valeri Brainin, who created and implemented his system of music education. He already has his followers in Ukraine.

“Today few people are able to listen to the music and read the information, which has been encoded in it. Music is perceived on the level of emotional impression, general sounding, but people simply don’t notice the rest of the details. Not in the last turn it is connected with the fact that during the past 200-300 years the music has become so complicated that its semantics cannot be understood by an average person. Only proper music education and the experience of listening to the music can help in this.”

L.H.: “Incidentally, in my time I proposed to create on the National Radio a program series ‘Music under Magnifier.’ At the outset of his composer’s activity Stockhausen hosted a similar program on a radio in Cologne. But my idea was rejected.”

It’s a pity. When people are able to listen to serious music, this is a totally different society.

O.Shch.: “A hard task is to speak about complex things in a simple human language.”

L.H.: “Indeed, this musicology language in which reviews are written… Who is going to read them today?”

O.Shch.: “I call it a disease of metaphorical musicology and criticism. You should speak about music as about music, don’t be comparing it with painting, landscape, or emotions. Over the country there are only few people who are able to react to one or another music event professionally.”

“THE DIKTAT OF MANAGEMENT IS FREQUENTLY CRUCIAL”

L.H.: “I think that current indifference of the young has been largely caused by total dominance of television. Previously people used to read much, later television broke the society’s habit of reading, as a result imagination has grown poorer and abstract-logical thinking narrowed.

“The low level of music education in Ukraine is connected specifically with the lack of knowledge of the contemporary world music. Unfortunately, the scanty funding does not allow purchasing the needed equipment for music libraries of our schools, colleges, conservatoires, and music academies. However, the situation is gradually improving – owing to the Internet, again.

“The entire performing activity of Sviatoslav Richter was taking place before my eyes: I went to his concert for the first time when he was very young and I was a student of the ninth form. Richter is not with us anymore. Very much regret that he has never performed the compositions which in my opinion are central in the piano literature of the 20th century, Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jesus by Olivier Messiaen. Say, he started to perform Weber’s variations for Hindemith’s suite as late as in 1989. Why? The well-known pianist Claudio Arrau, as long as he was a regional performer and toured only the countries of Latin America, had quite a broad repertoire and performed ‘own’ Spanish and Latin American composers. When the question arose about his advancement in the world piano ‘table about ranks,’ it was explained to him that he had to narrow his repertoire to the so-called iron set: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Shubert, Liszt, maybe Rachmaninoff, and as an exception Debussy and Prokofiev. The dictate of the manager, who naturally orients at the absolutely sure thing, turned out to be crucial.

“This is the very reason why new compositions very rarely and with great efforts find their way to the broad audience. Some pianists of the ‘higher league,’ such as Italian Maurizio Pollini, include from time to time the works by Boulez in their programs, and Odesa-born Shura Cherkasky has played even Stockhausen’s works, but those are rare cases, which do not lay a key role.”

O.Shch.: “And it seems to me when a modern composition is being performed along with the works of classics, it adds more responsibility to its author. But you are right, contemporary classic music is frequently marginalized and exists mostly in the festival format.”

Mr. Hrabovsky, what does the modern music life look in the US? Around what do the modern composers consolidate?

L.H.: “The whole new music in the US is focused mainly in the universities. Since American universities are for the most part located in comparatively small towns, the broad audience in big cities hardly knows anything about the stormy music life they are leading. For example, one of the most influential labs of computer and electronic music has been created at the Illinois University. The music they create is almost not performed in philharmonic societies, again because the instructions of managers and the financial policy, but it is performed in the universities.”

How does a Ukrainian artist feel abroad?

O.Shch.: “I for one since the beginning of my studies started not just to do my ‘homework,’ like pupils do, but create something in the context of the entire world culture. I felt the great ones behind my back, such as Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and Shostakovich. And I was composing music with this very feeling, but it won some response when it reached the West. It was hard to confirm my position here, in Ukraine, though, but this is a typical situation. Every country has a swamp, whose inertia you have to combat all the time. And those who take this up seriously are perceived by the surrounding, as a rule, in a very jealous manner.”