What do the giant Kalevipoeg from the eponymous Estonian epic and the hero of Oles Honchar’s novel Perekop about the war of 1917-20 Danko Yaresko have in common? Both works were illustrated by Serhii Yakutovych in the 1980s. In both cases, the artist, who was a scion of a famous creative dynasty, was creating a powerful image of the hero. Now these series of illustrations can be seen at the exhibition “Serhii Yakutovych. Idols” at the art center “Ya Gallery” in Kyiv.

THE EPIC CONFLICT

“The theme of heroes, which is raised in the exhibition, is always highly ambiguous, and it is so now too. Actually, who is the hero?” the curator of the exhibition Polina Limina asked. “Two series, dissimilar in stylistics and significance, are on display here. Honchar’s Perekop is an agitprop Soviet fiction book dealing with revolutionary topics. Kalevipoeg is an Estonian epic, which needed to be made relevant again in the Soviet Union in order to insert the Estonian culture into the general context. The two are quite different, but both turn to the theme of heroes. When they are shown in the same space, it can create a kind of conflict, a collision, which helps to demonstrate additional meanings involved in the concept.”

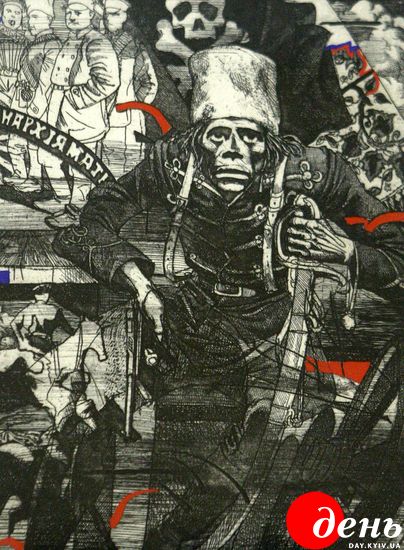

MAKHNO. AN ILLUSTRATION TO THE BOOK PEREKOP, 1987

A total of 44 works are presented at the exhibition, accompanied by the books Kalevipoeg and Perekop. The graphic works come from the Yakutovych archive, which is currently studied by the Ya Gallery team, led by the founder of the art center Pavlo Hudimov. Limina remarked that these works had not been exhibited since the late 1980s if not longer, and very few people had ever seen them.

HERO, ENVIRONMENT, LOVE, ENEMIES

The debate around the heroes is reflected also in the fact that the works of the two series are “mixed-up.” Kalevipoeg on horseback with a sword raised over his head can be seen next to Yaresko, also on horseback and looking at the viewer with piercing eyes. Love stories and images of enemies from both books are also exhibited next to each other.

As Limina noted, the exhibition is notionally divided into four parts. One room houses works featuring both heroes and the environments in which they live and fight. The second room reveals the relationship between the hero and his woman, love stories, as well as the theme of enemies.

AN ILLUSTRATION TO THE BOOK PEREKOP, 1987

“It all started with Kalevipoeg,” Limina recalled how the idea of the exhibition appeared. “This is not a very prominent position among Yakutovych’s works. I looked at the book, and when I thought of displaying Kalevipoeg alone, it seemed to me that it might fail to reflect the artist’s impetuous nature. It does not have its own internal conflict, it needs to be confronted with something, provided with a contrast, so that it becomes more than just a very well-made legend. For me, Perekop has always been like Kalevipoeg’s opposite number in the legacy of the same artist. Therefore, the book with the Estonian epic was the initial impulse, but Perekop came to join it later.”

TOPICAL “BEASTS”

Yakutovych depicted Nestor Makhno very much like an ape in Perekop. “It deserves a separate discussion – why the enemies were commonly reduced to beastly images. Speaking of the late 1970s and the 1980s, it was often used to portray the ‘American enemy’ as well. For example, a capitalist was depicted in the form of an ape or a pig, since precisely these animals were considered the personification of hostility in the collective public opinion. Here, it is transposed into more distant historical stories with a certain irony,” Limina commented. By the way, something beastly, wolfish is present in Yaresko’s depiction as well. It brings to one’s mind totems, which were actually heroes for the primitive people “at the beginning of time.”

Regarding the opportunistic nature of Perekop, Limina said: “Of course, there is always the financial aspect to the commission, but Honchar’s Perekop differed from other opportunistic works. Also, this is the only book work of Yakutovych done in the period when he turned to more modern themes and away from depicting the Cossacks and epic stories. It seems to me that it also played a role, as he wanted to try his hand in a more contemporary-themed project.”

Illustrations in Perekop are special in that they contain colored fragments. “While working on Perekop, Yakutovych experimented with color, it is one of the few book series of those years which he also painted with watercolors,” Limina remarked. Blue, red, and green ribbons designate different political forces, so the reader can determine which side this or that figure represents.

LOOKING BACK AT AN IDOL

Finding the name for the project was an issue in itself. “Were we to call the exhibition ‘Serhii Yakutovych. A Hero,’ it would have immediately created an association with the artist. Although I consider him to be one of the best in the 20th and 21st centuries, I do not want to predispose the viewer from the start to thinking that they are going to the exhibition of, let us say, a heroic artist. I try to avoid ascribing to artists clear traits of prominence, fame, heroics or something like that,” Limina thought aloud. “Another issue is that the word ‘hero’ immediately associates in one’s mind with something close and not distant in time, while here we turn to history, to events we can look back at from a certain distance. As for me, this is a fairly convenient division, as speaking of an idol, we speak about something that has already been relegated to the past, and now we can analyze it.”

This idea is reflected in the curatorial text accompanying the exhibition: “An idol has already firmed up, taken a certain shape, just as a visual work is completed; meanwhile, a hero appears to be more dynamic, indeterminate, and variable. The first one is easier to analyze, the second one is easier to take inspiration from.”

AN ILLUSTRATION TO THE BOOK KALEVIPOEG, 1981, DONE IN THE ARTIST’S OWN TECHNIQUE

TO MEET KALEVIPOEG

In a sense, Yakutovych met his Kalevipoeg on a Tallinn street. The artist mentioned this in his autobiographical records. “Heorhii Yakutovych [Serhii’s father, an iconic graphic artist. – Ed.] suggested that he needed to enter this culture, to see these people. Serhii went to Tallinn for that very purpose and actually saw this type on the streets of the city, meeting a very tall, athletic blond young man,” Limina said. By the way, Kalevipoeg’s plot originated with ancient folk tales, and it emerged as a literary work in the mid-19th century, when it was shaped as one by the educator and physician Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald, while his friend Friedrich Robert Fahlmann was the author of the idea. The work was presented as a reconstruction of the oral epic. Estonia was then part of the Russian Empire, and the first version of Kalevipoeg failed to obtain a censor’s approval.

A MIRROR OF SOCIETY

The images of Kalevipoeg and Yaresko have a certain kind of exaltation in common. It is clear that the author tries to downplay negative traits in the figure who is claimed to be a hero, while positive ones are put to the forefront. “Also, the hero’s traits seem to be a reflection of what their society wants to see. So, another shared feature of both works is their use of a laconic dream image of one’s own people,” Limina said.

The search for a hero is very relevant for the contemporary Ukrainian society as well. “This exhibition can help anyone who thinks about the modern hero-making. First of all, it helps to understand for oneself that the hero is often somewhat artificial. Traits which we ascribe to the hero do not come from nowhere, they often do not belong to a particular person either. It is said that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and in the same way, the image of a hero can tell more about us,” Limina said. “Perhaps even our contemporary notion of heroism, which we ascribe to different people, is more likely to show what we lack.”

Those trying to understand what we lack and get acquainted with Yakutovych’s Idols can visit the Ya Gallery till August 28. Also, one can read about the theme of heroes in the artist’s legacy in a story which has recently been published on the Yakutovych Academy website, it being a media project on art and society as seen through the prism of the history of the Yakutovych dynasty.

***

One can find a concise retelling of the Estonian epic on the Internet. After a series of adventures, Kalevipoeg became king of Estonia, and was quite a successful one before eventually succumbing to the curse of the blacksmith, whose son he had killed at the beginning of the story. A magical sword cut off the hero’s legs. The god Taara revived him and sent him to guard the gate of hell. Having been removed from the pedestal, the hero now guards antiheroes. Still, the pedestal is never empty.