This time, the actors from Boris Eifman’s St. Petersburg Ballet Theater presented Tchaikovsky, a play shown to the public in Kyiv, Odesa, Dnipropetrovsk, and Kharkiv, the tour being organized by Piligrym company. Each performance by this St. Petersburg theater is a landmark event, being something more than just ballet: a parable, a revelation, and a reflection.

Critics label Boris Eifman’s company a “unique phenomenon in the modern choreography.” His productions are distinctively dramatic, permeated with philosophy and subtle psychological insight. Overstepping the bounds of innumerable taboos, the choreographer expanded the rigid classical framework, yet remained faithful to the canons in creating a modern ballet and translating drama into dance and plastique.

Tchaikovsky begins and ends with the scenes of the composer’s death. They say that at his last moment, man sees a kaleidoscope of his life – and this is what underlies Eifman’s production. The spectators can see Tchaikovsky’s revived memories, mixed with his delirious visions and hallucinations. The maestro (Oleg Markov), whose restless soul cannot find ultimate peace, is visited by the images that had been tormenting him all his life: his Double, the composer’s alter ego (Aleksei Turko), the black birds of his thoughts, white Swans, the Fairy Karabos, Nutcracker, assorted playing cards, the Queen of Spades, the perfect young Prince (Ivan Zaitsev), the maiden (Zlata Yalinich), Miliukov’s insane wife (Natalia Povorozhniuk), his benevolent angel, Nadezhda von Meck (Choe Lina), and also friends and admirers (his characters and contemporaries whose parts are performed by the ballet artists).

Tchaikovsky’s thoughts travel to the places where he can enjoy beauty and harmony – in reality, he is an outcast. Even married, he cannot tame his passions as his flesh is at conflict with the existing moral standards. That is why loneliness became his lot.

Viacheslav Okunev’s set design is very laconic. In the middle of the black backdrop there is a vignette window with changing images of St. Petersburg cityscapes, theater boxes, and a lake; the bed where Tchaikovsky lies raving in agony, a barre, a card table – gradually, Tchaikovsky’s world is becoming narrower and narrower, eventually transforming into his deathbed.

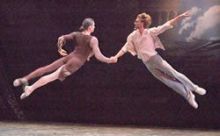

The performance tells a story of the composer’s struggle with himself and with the circumstances, and of his artistic searches, loves, and passions. The production is so expressive, plastic, dramatic and sensual (with its complicated pas, pirouettes, and breathtaking lifts), and musical accents are so aptly made (with Tchaikovsky’s works being played), that you cannot take your eyes off the stage. You are amazed at the dancers’ virtuosity, their dramatic talent, and the choreographer’s art.

Today Eifman is referred to as a guru of choreography. Critics try to figure out his secrets, while the younger colleagues try to copy off of him. Eifman’s ascent towards worldwide recognition began long ago, back in 1977, when his theater was created. By the way, it was Kyiv which was the first to see the performance by this young yet original company.

Back then, Eifman’s experimental ballet The Boomerang, staged to the music of Pink Floyd, impressed the spectators and, moreover, united many people who developed a lifetime passion for his art. In the Soviet times, using the music by Pink Floyd, John McLaughlin, or Rick Wakeman of Yes amounted to no less than a rebellion. The combination of choreographical compositions with the music which was strikingly emotional and free from academic cliches earned Eifman a reputation of the “breaker of the principles of ballet.”

The theater’s repertoire helped form a company with a specific plastic thinking. The artistes, with their brilliant mastery of both classic and modern dance, have a gift for transformation on stage.

Today, Eifman is the creator of a new school of acting, with a service record including almost 50 ballets. He has created his own choreographical language, expressive and bright. His heroes differ from fairy-tale princes and princesses. Rather, they are symbols of various historical epochs, such as the playwright Jean-Baptiste Moliere, the composer Tchaikovsky, George Balanchine, the founder of the modern ballet, the ballerina Olga Spessivtseva, and so on.

The Day talked to Eifman over the phone. He had not gone on tour, being busy with a new art project, which he keeps secret for the time being. However, he confessed that he believed the Ukrainian capital to be a lucky charm for his theater, and his dancers would say, “If the Kyivites welcome a production, it is sure to be liked by the public in other cities.”

None of your ballets is meant to entertain the public. They are a kind of revelation, psychological and dramatic action, translated into the language of dancing. How can you make the spectators sympathize?

“The theater aims at touching the spectators’ souls and leading them, through stirring their deepest emotions, to a catharsis, so that their souls echo to everything they see on stage and get charged with new energy. For me, ballet is not about amusing the public, but rather having an opportunity for a frank conversation about important, universal problems.”

Boris, you have gathered a company of excellent dancers. Many Ukrainian artists have also been to Eifman school, for example, your current leader Nina Zmiievets (Spesivtseva in Red Giselle) comes from the Kyiv school of dancing. What are the criteria for picking dancers for your theater?

“I try to keep in touch with various schools of ballet. Any dancer can come to a casting call and show what they can do. Besides Zmiievets, our company also includes Lanovy, who has recently graduated from the Kyiv Choreographic School, and a few danseurs and danseuses in the corps de ballet. I have a great respect for the Ukrainian school of ballet, and that of Kyiv in particular, as it trains topnotch professionals.

“Occasionally, we refresh the company. Ballerinas can be up to 172 cm tall, but as to danseurs, we want them quite tall, 182 cm and more.

“I do not pick only those dancers who can ‘dance easily.’ It is rather those actors who can convey my choreography and my plastic language. To dance in my ballets, they must have certain lines, and it is not a matter of preferences, but rather the matter of expressing my ballet ideas via choreography.

“On the whole, modern choreography is the dance of lines, and I like these lines to be clear-cut because it is them that add the expressiveness and beauty to the ballet. Our dancers are distinctively artistic and, besides professional skills, have to be able to create images on stage, to think independently, and at the same time to stick to my ideas in order to co-author the performance. Also, our theater requires lots and lots of hard work.”

Let’s open the door to your artistic workshop, shall we? When you start working on a new production, do you first mull over the dramatic storyline, or do you get your ideas while listening to the music?

“It depends on what your aim is. For example, when I was working on a ballet to Mozart’s music, I listened to his pieces, plunged into his artistic atmosphere, and built the drama based on the music. However, more often I will work with literary sources: writers’ works, memoirs, diaries, and reminiscences of the contemporaries. Then, when I have invented the plot, I complete it with the musical foundation, and then start looking for the best way to convey my idea via choreography and plastic movements. In conclusion, there is the improvisation of movements during the dance.

“It is when I enter the ballet studio that the birth of the ballet begins. The birth of a concept is a complicated process and sometimes can get unpredictable. It’s hard to say where I get my inspiration, but it never leaves me. Ideally, all the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle must fit in at once: as a rule, music first, then the dance, and, simultaneously, working with the artist.

“The drama for my ballets comes from the classical Russian literature. I began to compose ballets quite early (at 16 I already had a company of my own). Many years have passed since then, but I still tend to stick to good, high-quality literature, which is my foundation.

“In my performances, I try to discover the unknown in the known – I have never illustrated a text. However, I have produced some plotless ballets, such as Requiem, My Jerusalem, and plays telling of some men of the arts, such as Moliere and Tchaikovsky, as well as chamber ballets Autographs and Metamorphoses, and also buffo ballets The Crazy Day, or The Marriage of Figaro, The Twelfth Night, and Intrigues of Love. Yet in my opinion, literature is that basis for drama without which the theater cannot exist.

“In my productions, I want the spectator to be led by the music. It is easier to do through classical music. However, for Red Giselle I chose Alfred Schnittke, whose music was discovered by some of the spectators only after our performance. While working with classical music, I edit it, and the audience will sometimes think that this music was created specially for our production.

“Music, light, costumes, and dancing are all combined to create an original, independent image, and it is impressed in the spectators’ memory. Variegated perception allows to treat good music as non-canonical. The power of many musical masterpieces is in their ability to trigger different impressions in different people at a time.

“My chief task is to enrich the traditional perception of ballet. This is the main peculiarity of my creative work. I am patient and methodical in my creativity, and my dancers and I pay a high price for our success.”

You have staged several ballets to the music by Tchaikovsky, and the play Tchaikovsky tells the story of the composer’s life. How was this ballet born?

“Tchaikovsky is one of my favorite composers. I have staged six performances to his music, but I have never staged any of his ballets (The Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker). Tchaikovsky’s music is charged with emotion; it evokes dreams and fantasies and makes us better.

“You know, I once wondered: How come that such a successful and famous composer wrote such tragic music? I plunged into his biography and learned about his sufferings, about the infernal torture his soul went through and provoked the tragicalness of his music – and I began to perceive it quite differently.

“Tchaikovsky was homosexual and suffered because he perceived it as a sin. He wrote in his letters that he would like to be like all the others, but nature endowed him with both talent and sin. That is why, in his music he expressed the anguish of his soul, being torn between God and the devil. His soul, morality, and his suffering aspired to God, while nature weighed down on him, pushing him towards the devil.

“His tragedy lay in the fact that he was aware of his split identity, and therefore, he suffered and agonized. My ballet is not the story of Tchaikovsky’s personal life, but rather an attempt at materializing the tragic element in the composer’s music. Why did this genius have recurring thoughts of suicide and write letters filled with pain and despair?

“A composer’s creative process is always a mystery. It is as hard to understand him as it is to penetrate his personal life. First, how do you find the boundary where everyday life ends and creation starts? In an artist’s life, these two aspects of life are like communicating vessels, where joy and angst, victories and defeats mix, where the apotheosis of thought is replaced with a whirlwind of passions.

“He is always surrounded by delighted worshippers and enviers, admirers and slanderers. Tchaikovsky’s life is one endless dialog with himself. His work is a confession filled with pain and anger.”

Which of your latest ballets are recorded as films, and where can one see them? And also, I would like to congratulate you on the theater’s new media center.

“The ballets Anna Karenina and Onegin were shot by a wonderful Italian cameraman, Daniele Nannuzzi, who has worked with such great masters as Sergei Bondarchuk and Franco Zeffirelli. It was hard to build scenes, frame shots, work with actors, and do it all simultaneously.

“We make recordings of things in order to preserve our repertoire for the ballet history. The equipment was presented by the World Bank. Maybe, these ballets will get shown on TV or at some festival. Quite recently, our theater also acquired a state-of-the-art mobile multimedia center. Now we can record our rehearsals, productions, didactic DVDs, and, in the future, broadcast our performances online on the Internet.

“I have always been envious of the Mariinsky, Bolshoy, and other theaters which have their own media studios. Our theater will be 33 this year, but with all that, it has only a very small archive. The multimedia center will allow us to register the stages of creating a ballet, and show to both amateurs and professionals what the art of creating a dance is.”

You have created your own choreographical language. Could you share your vision of the direction ballet is going to take further?

“It is hard to define one direction. Today, the crisis of modern choreography tells all over the world: the lack of new ideas, names, and forms. I am often invited to sit on the panel at various international competitions, and I am often appalled at the slump in the younger choreographers’ creative potential.

“The main problem of today is the lack of new choreographers, who would be able to become worthy followers of the great ballet masters of the 19th and 20th centuries. The shallowness of the choreographical idea results in a lot of ballet trash, a lack of professionalism, and falsification on stage. In its turn, this causes the decreasing interest among the public.

“In my theater, I aspire to preserve Slavic traditions, i.e., develop the best of what has been created by our predecessors, and on this basis, create my own art. For me, succession of generations really matters. For example, here in Ukraine Radu Poklitaru’s work is interesting to see (the Kyiv Modern Ballet). I have seen several of his productions and become interested. They were staged by a talented person, and he leads his company along his own path in art.

“Nowadays, more and more of the so-called avant-garde choreographers, who used to stage abstract compositions, are turning to the ballet with a plot. What I have dedicated my whole life to is now finding response even in their work. So I pin my hopes for the ballet’s future on the theater. Where the art of ballet was born, it will eventually return.”

Don’t you mind when the younger colleagues “quote” you by copying off of you in their productions?

“Each young choreographer goes through a period when s/he is prone to influence by idols. I did not avoid that either. I admired Maurice Bejart’s work, but soon I was able to find my own language, creating my own ballet.

“Quoting won’t do any harm, but here it’s important not to stick to it and learn to overcome the authority’s influence, accumulating the best of your predecessors’ experience and creating new, original work.”

As a rule, your theater brings one or two productions on a tour. Aren’t you planning a big tour of Ukraine, because here there is an entire generation of “Eifomans”, the admirers of your ballet? Would you like to stage something in Kyiv?

“It has been my dream to go on a big tour in Ukraine. I adore Kyiv! This is no compliment; it’s the real truth. It is your city that our touring epic started from. The theater’s first guest performance was on Oct. 30, 1977, on the stage of the October Palace (now the International Center for Culture and Arts).

“We showed The Boomerang to the music by Pink Floyd. I want to emphasize that it was 32 years ago, when the Soviet party propaganda was at full swing, and the immense success of our ballet in Kyiv helped us believe in our own strength and gave us certainty about choosing our own path in art. At the time, we were reproached for being ‘prone to the pernicious influence of the West’ – and back then, that was quite enough to stifle a young company.

“I’m grateful to the Kyivites, who not only supported, but also acknowledged us, and it became a turnpoint in our biography. It is from Kyiv that our theater launched its international tours. I want to use The Day to say a big great thank you to everyone who came to see our first performances and who still loves us and shows interest in our work.

“On our international tours (in the USA, Germany, and Israel) I came across many former Ukrainian citizens, former Kyivites, and they remembered that performance and our first tour. I hope that we will continue to keep Kyivites informed about the new productions in our repertoire.

“As far as a big tour goes, we want to involve patrons and donors – and we are ready to come to Ukraine. Concerning a production in Kyiv – if the administration of the National Opera agrees, I will try to adjust my plans and consider their proposals carefully. The ballet company here has a very big potential, and it would be very interesting for me to work with Kyiv artists.”