In 1859-61, Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian career diplomat who was later to become the famous German chancellor, was posted to St. Petersburg as Ambassador of Frederick William IV of Prussia. Russian noblemen at the tsarist court knew about his sharp sarcastic wit and sought conversation with him, the more so that there was the acute subject of Alexander II’s vast empire being on the threshold of long-overdue, far-reaching economic, social, and political reforms. To the thinking part of society, which included quite a few staunch conservatives, it was obvious that something should have been done about the reforms for quite a while already. No one could regard as modern a 19th-century feudal country with several dozen thousand big-time landowners of noble birth being in full control of property, and even the lives of tens of millions of Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Georgian, and Moldovan serfs who constituted 80 percent of the empire’s population. Many realized that this situation could not go on.

In October 1859, Count Nikolai Milyutin, a celebrated liberal and outspoken exponent of reform, visited Ambassador Bismarck to consult him on the forthcoming historic transformations. Bismarck smiled, paused, then said, “I wish you success; the cause you are embarking upon is important for the state. Just remember that carrying out such reforms in a country like Russia is like dancing on a razor’s edge.” (This quote is found in the memoirs of Nikolai Milyutin’s brother Dmitry, published in 1903.)

I will now try to demonstrate how Alexander II and his milieu danced on that razor’s edge in 1856-61, how the project of the Great Reform evolved with its inner controversies, and how that razor, contrary to the reform, became the deadly hatchet of the revolution (not coincidentally, Chernyshevsky’s call on Russia to take up the ax came in 1860).

About the inner controversies. To begin with, Alexander II had a direct impact on the essence, rate, trend, and course of the reforms that were essentially revolutionary (considering that a new social system, one rooted in the market and capitalist by nature was being established). Those reforms were the first sure sign of a true revolution. They were radical and by no means colorful tags worn by the participants in any upper-echelon coup. The monarch was an inheritor of his father Nicholas I’s political legacy, authority (to Taras Shevchenko Nicholas I was an uncouth bear and boor), as well as his ideology, along with inveterate conservatism and dedication to the “underpinning principles.” Alexander II, however, was doubtlessly aware of the inevitability of reform. He made his well-known statement addressing the Muscovite nobility on March 30, 1856: “Better to abolish serfdom from above than to wait till it begins to abolish itself from below.” This gave an impetus to the discussion of the problem among government officials, noblemen, and even in the press (this was unthinkable under Nicholas I). Yet there remained that “fatal controversy” which left an indelible mark on all of the tsar’s political decisions made with the millstones of the historical necessity of emancipation and plain conservative stereotypes around his neck.

What made this autocrat delay the reforms time and again, walking round them like a cat round a bowl of hot milk (as described by a witty contemporary)? Was he to grant plots to the emancipated serfs? (Granting them personal liberty was not to be disputed.) If so, how large should each plot be? What should be the legal procedure? That was the issue, with other closely-related ones following. Was the tsar to preserve the nobility’s “sacred votchina land ownership” or let the peasants have the plots originally allotted? (In the end, the drafting committees, formed under the tsar’s edict of 1858, would opt for latter approach — an important decision.) Should the landowners’ plots be bought out and how: on a legally peremptory basis or through voluntarily measures? For what term? How should the government be financially involved?

Incidentally, there were a number of purely financial factors that made these reforms absolutely unavoidable. Most landowners in mid-19th-century Russia (among them Ukrainians, as evidenced by the notes of Vasyl Tarnovsky, a well-known public figure and landowner, which notes were regularly made known to the tsar), had no way to increase their crops by expanding the areas farmed. Nor could they increase the agricultural output because of the insurmountable barrier of forced serf labor. Any landlord’s peasant, when working his master’s field, using his own tools and horse, primarily wanted to exert as little energy as possible, so he could then work his own plot. The landowner, whose interests were quite the opposite, couldn’t help becoming increasingly aware of the uselessness and wastefulness of forced serf labor. A landowner free from caste egotism also realized that his farming business, given the market relations, objectively tended to expand, yet couldn’t do so under the feudal system. That was the crux of the matter.

Apart from the legal and economic aspects to the emancipation reform, there was the administrative one that couldn’t be ignored. Who would carry it out, the state or the nobility? In other words, who would assume the responsibility? Also, could such reforms be implemented using the good old authorities and institutions? Alexander II and his advisors should be given credit for saying no. A Secret Committee for Peasant Affairs was established (later renamed Chief Committee…), followed by the drafting committee that reported directly to the tsar and was responsible for working out certain aspects of the reform.

Noted figures became members of the drafting and gubernia committees that prepared the reform with an eye to local conditions.

Adjutant General Yakov Rostovtsev, Alexander II’s close friend, wrote in a memorandum addressed to the tsar: “None of the attempts made in Europe in order to change the peasants’ way of life can serve as an example for Russia. There they were concerned not about the emancipation of the peasants (the latter had long achieved personal liberty), but about the allocation of plots as their property. Russia has to solve two problems. First, [granting the serfs] personal freedom; second, giving the peasants parcels of land. As it is, Your Royal Majesty and the Committee have deemed the allocation of plots impossible; buying out plots from landlords would cost the government up to one billion silver rubles (sic). The government doesn’t have even a small part of this staggering sum. Issuance of bonds or a loan this big would cause a financial revolution in Russia. Moreover, Russian peasants, save for a handful of small gubernias and certain industrial areas, would never comprehend the confusing procedures of buying out plots over several decades (precisely what would happen, eventually leading to the Russian revolutions — Author.); they would say, ‘So much for our freedom; all they did was to increase the tax.’” Rostovtsev represented the left liberal reformer wing. He died a sudden death in February 1860, but not before he told the tsar at his deathbed: “Your Majesty, have no fear!”

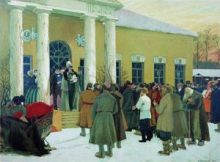

Followed five years of heated debates, political struggle, and endless compromises (after Rostovstev’s death the reformer bills began getting increasingly on the right, in accord with Alexander II’s inner convictions) until on February 19 (March 3, New Style), 1861, Alexander II’s Manifestation Manifesto was solemnly proclaimed to the accompaniment of church bells, along with a set of associated legislative acts, including the “Regulations Concerning Peasants Leaving Serf Dependence,” “Local Regulations,” and “Additional Rules.” A number of local regulations targeted the Ukrainian territories.

Alexander II believed the situation had to be changed: “Examining the condition of classes and professions comprising the state, We became convinced that the present state legislation favors the upper and middle classes, defines their obligations, rights, and privileges, but does not equally favor the serfs, so designated because in part from old laws and in part from custom they have been hereditarily subjected to the authority of landowners, who in turn were obligated to provide for their well-being. Rights of nobles have been hitherto very broad and legally ill-defined, because they stem from tradition, custom, and the good will of the noblemen… We have left to the nobles themselves, in accordance with their own wishes, the task of preparing proposals for the new organization of peasant life, proposals that would limit their rights over the peasants… Through members of the gubernia committees, who had the trust of the nobles’ gatherings, the nobility voluntarily renounced its right to own serfs… And now, Orthodox people, make the sign of the cross, and join with Us to invoke God’s blessing upon your free labor, the sure pledge of your personal well being and the public prosperity.” The numerous associated regulations granted the emancipated serfs personal liberties and civil rights. Thus, they no longer had to ask the landlord’s permission to marry; each peasant had the rights of a legal person, they could sign contracts and assume obligations individually or as members of a community, practice free trade without trade certificates and without paying customs duties. A peasant became a legal person in terms of civil, administrative, and criminal law. He had the right to take part in elections and could be elected to public office, as well as to enroll in the “general educational establishments.” Finally, the emancipated serfs could from now on be punished only by a court of law (although with the smart reservation that they could also be meted out punishments by a duly appointed government or public authority).

The Great Reform was doubtlessly a big step forward. But then why did it fail to reach its target (namely, to prevent peasant rebellions, often violent in nature; though this objective wasn’t always stated). There are a number of reasons. First, millions of peasants being “temporarily obligated” under the Manifesto to make land redemption payments over the decades — and this considering that the peasants regarded that land as their own anyway, given to them by the Lord. This couldn’t but make them suspicious of the Great Reform as being carried out for the benefit of big-time landowners (which was largely the case). Second, the government consciously preserved and in every way supported the obsolete mir peasant community, hoping thus to prevent social upheavals (this community would endure even Stolypin’s reforms), but it achieved the exact opposite. Third, there was Alexander II’s hesitant approach, his deviations from the state course played a major role. Thus, he relieved a considerable number of ranking bureaucrats of their posts — people with whom he had prepared the reform — so it would start being implemented after 1861 by considerably more conservative individuals, among them Count Pyotr Valuyev (whose name is particularly sinister for Ukrainians).

Small wonder that a large part of Ukrainian and Russian peasants would neither accept nor trust the reform. One is reminded of Shevchenko’s “Do you await, / Perhaps some dark, distressful hour to come? / Look not for pleasant times; do not await / Your longed-for freedom — it has fallen asleep: / Tsar Nicholas has lulled it off to slumber.” Characteristically, the emancipated serfs in the village of Bezdna, Kazan gubernia, announced that the Emancipation Manifesto they’d heard ceremoniously read was the landlords’ fabrication, and that the tsar had actually granted the serfs freedom and land. Land! Troops were summoned and opened fire on the rebellious crowd, killing several dozen peasants. In another Russian village, Krandiyevka, the peasants, after hearing that they had to actually keep toiling for the landlord, to buy out their plots, declared that they would die rather than succumb; that they would die for the Lord and for their tsar. Once again tsarist troops opened fire, killing 11, wounding 31, and then flogging 165. Many peasants were exiled to Siberia. Khudiakov, aide-de-camp of General Dreniakin (the latter was in charge of the punitive operation), later testified: “They [the soldiers] flogged them so hard, chunks of flesh were flying… ‘So do you repent? Will you do your work?’ They asked a small muzhik whose back was one big ugly wound with birch twigs sticking out here and there. The man sighed, as though with relief, then blurted out: ‘No, I won’t and you can kill me.’ The flogging resumed, but the peasant wouldn’t let out even a groan.”

At present Ukrainian society needs reforms, yet the public attitude to them reminds one of what happened 150 years ago. Today, he who orders the reforms (in social rather than personal terms) expects them to serve his interest. The point is not even that, over the past 20 years, each of the Ukrainian governments has paid lip service to reforms, but that the semifeudal system of ownership and social relationships has remained the same. What public confidence can one expect? The trouble is that the time for reforms, when they can still improve or even save the situation, is running short, as in Balzac’s La Peau de chagrin (The Wild Ass’s Skin).