Whoever is capable of correctly understanding the causes of a defeat makes the first step on the road to transforming defeat into victory. Therefore, only the politician who can find the strength in himself to carry out this vitally important, honest, and responsible analysis of errors can hope to achieve his cherished goal. History does not leave a glimmer of hope for a narcissistic leader who suffers from egotism, which makes him view reality through rose-tinted glasses and believe that Clio, the muse of history, like Pushkin’s goldfish, will serve him.

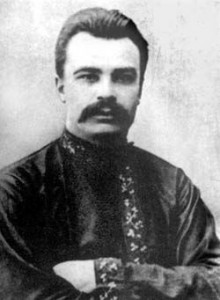

The Ukrainian national-liberation revolution of 1917-1920 ended in tragic defeat. Its leaders, one of whom was the outstanding writer, publicist, and political and civic figure Volodymyr Kyrylovych Vynnychenko, faced the highly complex task of drawing bitter, inevitable lessons from the rich experience of the revolution, and by generalizing them to correct their vision of their country’s future. This was probably especially difficult for Vynnychenko, who was the first to write and publish a three-volume series of memoirs entitled Vidrodzhennia natsii [Rebirth of a Nation]. Published in Vienna and Kyiv in 1920, they were fundamental in concept and scope. Now, more than 85 years later, this work remains a truly unique source on the history of the Ukrainian liberation struggle in the early part of the 20th century.

Every historian recognizes the subjective limitations of the memoiristic genre, especially of memoirs written by famous political figures. Yet Vynnychenko’s three- volume work, perhaps like no other scholarly study devoted to this period, helps us fully and objectively picture not only the course of specific events but also the sentiments, mistakes, and illusions of different groups, classes, and parties in Ukrainian society of the time. This explains the importance of Vidrodzhennia natsii, a book that should be required reading for Ukrainian patriots today. But it has never been, not in the least because it is published very rarely and in limited quantities.

Those who know what kind of person Vynnychenko was and what his character was like — he was far removed from the “Olympian” impartiality desirable for the memoiristic genre — will immediately grasp how difficult it was during the writing of his memoirs to adhere to his own guiding principle that he describes in the prologue: “Conscious of the importance of truth and the significance of a sincere, straightforward, and honest exposition of events, I will make every effort to distance myself from any national or partisan favoritism, all personal sympathies or antipathies, and will view the entire progress of our movement with all the objectivity of which I am capable.” This was an incredibly difficult, nearly superhuman, task.

Moreover, as Vynnychenko himself pointed out, his work was being created at a time when “the future of Ukraine was enveloped in the smoke of bloody hatred, greedy encroachments from enemies, our helplessness and impotence” (July 1919). Still, thanks to his exceptional talent as a political writer, a “historian of modernity,” and even a profoundly discerning analyst (although not everything that he said can be accepted at face value), Vynnychenko accomplished a hugely important mission: he created a mirror in which, unexpectedly, even today’s Ukraine can see many of its own characteristics.

Of course, this brief article cannot provide a systematic and chronological overview of the contents of Vynnychenko’s three-volume work, which begins in spring 1917, when the Central Rada was established, and ends in 1919. I will briefly outline only the main problems addressed by one of the leaders of the Ukrainian revolution. On the opening pages of his memoirs Vynnychenko generalizes the tragic experience of the revolution that lasted for a little over two years, and provides a clear-cut, well-honed formula that the highest-ranking representatives of the current Ukrainian leadership would be wise to memorize: “Any law, any treatise is merely a statement of the correlation between the forces of two counteragents at any given moment; it is merely a temporary ceasefire. Genuine law and right is the law and right of force.”

This hardly sounds “democratic.” Yet Vynnychenko had every reason to say this. Most importantly, from his own observations and his participation in negotiations he was very familiar with the leaders of Russian democracy. These very people, their position and political practice, prompted the author of Vidrodzhennia natsii to write these bitter, merciless words.

According to Vynnychenko, April-May 1917 saw the formation of an ostensibly improbable secret union of the Russian ultra-reactionary with the Russian democrat. At the same time this union was quite predictable, if you consider the common material interests and national sentiments of these two “friends,” as the outstanding Ukrainian writer described the essence of this horrendous phenomenon. After all, “the Russian intellectual needed somehow to justify his conservatism and chauvinism. He needed any reason, no matter how meaningless or fictitious, to counter the Ukrainians’ demands and set his ‘pure mind’ at ease, a mind that was forced one way or another to recognize the equality (of Ukrainians and Russians — Author). Fully realizing the nature of its intellectuals, the Black Hundreds phenomenon brought him these reasons in the form of various rumors and gossip: ‘the Ukrainians are planning to proclaim a federation during their congress. (This concerns the slogan calling for an autonomous-federated structure of the newly- formed Russian state with broad rights for Ukraine. It was popular among most of the Central Rada members in spring 1917 — Author). The Ukrainians will expel all the Russians, Jews, and Poles from Ukraine; the Ukrainians are planning to dynamite all Russian schools; the Ukrainians are negotiating with the Germans in order to break through the frontline. These were blatant lies, but the Russian intellectual eagerly grabbed at them and used them to justify his use of force.”

It is very interesting to analyze the genesis of those insane shouts about “forcible Ukrainization” and the uproar that “the members of the Black Hundreds and the democrats” raised in 1917 around the question of schools at a time when, as Vynnychenko rightly points out, “the government had not yet issued a single decree to introduce the Ukrainian language in higher or secondary schools, not to mention lower and public schools; when not a single kopeck was allocated for Ukrainization out of those billions that were pumped out of the Ukrainian budget annually, while Ukrainian high-schools were founded in Kyiv only with private and community funds!”

Meanwhile, as early as April 30, 1917, a “Group of Indigenous Little Russians” (Black Hundreds in essence and liberals in form, Vynnychenko explains) sent the following telegram to Minister A. Manuilov of the Provisional Government: “In a free Russian state built upon strictly adhered laws, all citizens should have freedom of cultural and national self-determination and for this reason, those Little Russians who consider themselves Ukrainians, i.e., representatives of a completely separate nation, should enjoy broad freedoms of cultural and national self-determination, but (and Vynnychenko rightly underlined this “but” — Author) only on condition that there are no manifestations of forced Ukrainization of those Little Russians who consider themselves Russian and on condition that the status of official language is preserved for the Russian language.”

This telegram, with its telling heading, “A protest against the forcible Ukrainization of schools in Little Russia,” is an extremely interesting document. After all, today we still see political forces that are allergic to all things Ukrainian. Do I have to name them? You can hear these politicians on television every day. These demagogues scream about the “oppression and persecution” of the Russian language in Ukraine, which is why this language vitally needs the status of second official language. They use the same “arguments” that were once used by the “Little Russians.”

I must repeat that we may not agree entirely with all of Vynnychenko’s statements. But has history not proven the bitter truth of this writer’s indignant, sarcastic lines in which he describes the hypocrisy of a large part of the Russian “socialist” and “democratic” intelligentsia? “Offices, newspapers, and speeches are filled with quite honest words about the equality of all peoples, about the equal status of the Ukrainian nation and its rights. Meanwhile, in the kitchen and in daily life we see bayonets, fists, and slaps in the face of the age-old servant, who is infringing on the privileges and tastes of the ‘master.’ There is sincerity both there and here. Intellect lives one life and emotions — another. As expected, the psychology of the Russian intellectual, which formed under abnormal circumstances, could not change within a single month. The ceremonial, intellectual portraits remained portraits, but behind the portraits are commonplace, emotional black-beetles, cockroaches, and fleas. All people are equal, but every Russian intellectual addresses a driver or waiter in a customary, good-natured, and belittling way in the second person (“ty”). His emotions and practical mind have created in him an old-standing habit of viewing Ukrainians as ‘khokhols’ — as part of the Russian people, but somehow funny, immature, inferior — something along the lines of a driver or waiter among the national citizens of Russia.”

All the above does not mitigate the responsibility of the leaders of the Ukrainian national movement, who in the spring of 1917 displayed commendable trust and irresponsible, romantic “euphoria,” stubbornly refusing to face reality. (It is no accident that one chapter in Vynnychenko’s book is entitled “The Artlessness of a Relative Beaten to within an Inch of His Life.”) At the time Mykhailo Hrushevsky’s line of reasoning, much like Vynnychenko’s, was this: “We have become part — an organic, active, living, and willing part — of a single whole. Any separatism, any separation from revolutionary Russia seemed ludicrous, absurd, and nonsensical. For what? Where will we find more of what we will now have in Russia? Where else in the entire world is there a similarly broad, democratic, and all-embracing system of government?” This is why they decided to restrict themselves to demanding the status of autonomy for Ukraine within a single Russian state. This was their fatal mistake. October 1917 was just around the corner.

Vynnychenko was never an impartial chronicler who “is equally indifferent to good and evil.” For this reason, those for whom Ukraine’s independence is truly of ultimate spiritual value, not just political, cannot but heed the prophetic warnings and the passionate words that he recorded in his diary in 1917, as though they were written with the blood of his heart: “Oh God, how daunting and arduous the cause of reviving national statehood is! Although it may appear easy, self-evident, and natural in historical perspective, it takes superhuman efforts, trickery with desperation, anger, and laughter to drag these stones of statehood and use them to build this house in which our descendants will live comfortably.”