September 14 is the Day of Ukrainian Cinematography. Established in 1996, the holiday is relatively new. On the other hand, although almost 20 years have passed, even professionals rarely remember this date (perhaps, because it is changing every year: the second Saturday in September, and film-making industry has not been well-off during these years anyway) and congratulate each other on August 27. That is when the Day of Cinematography was loudly and joyfully celebrated before the Soviet Union collapsed. And for us, journalists from the film desk of Ukrainian television, it was a pleasure to prepare photographs of grand masters of the movie industry, reports from shooting areas, and film concerts cut from fragments of favorite films.

These memories came to my head for two reasons. Firstly, because many of the heroes of those times are not with us anymore. Programs were not saved. They were simply destroyed, without thinking that very little time would pass, and that documentary evidence might become precious. And secondly, on the eve of Kyiv Day script writer Liudmyla Lemesheva and director Serhii Lysenko received a prestigious prize, Ivan Mykolaichuk Kyiv Award (it is awarded annually to outstanding Kyivites in various spheres of art for considerable contribution into the development of the national culture and high professionalism). In this case, the award was given for the beleaguered documentary (its production, from start to end, lasted 10 years) Taiemna svoboda (Secret Freedom). It is about the happy and dramatic fate of Ukrainian cinematography from 1960 to 1990. About those cinematographers, whose names are an object of pride of our national culture, and who we want to greet in the first place on the Day of Ukrainian Cinematography.

“MY UKRAINIAN ANCESTORS NEVER BECOME SLAVES”

Secret Freedom is a portrait film. A portrait of the talented, joyful, penniless, and risky generation of film-makers of the sixties. In my book collection, I have books by Liudmyla Lemesheva Ukrainske kino: problemy odnoho pokolinnia (Ukrainian Cinematography: Problems of One Generation, 1987) and Profesia: actor (Profession: Actor, 1987). They featured Ivan Mykolaichuk, Leonid Osyka, Yurii Illienko, Mykola Mashchenko, Roman Balaian, Oleh Fialko, Kostiantyn Stepankov, Larysa Kadochnykova, Ada Rohovtseva, and other wonderful actors and directors, whose names bring to mind the outstanding films that made Ukraine famous. Also, with director Anatolii Syrykh, you made the film Ivan Mykolaichuk. Posviachennia (Ivan Mykolaichuk. Tribute). And finally, the film Secret Freedom.

For many years, even decades, you have been constantly coming back to the same theme, the same characters, the same films. Why? Do you think that this period of Ukrainian cinematography is not yet researched enough? Or does the factor of personal acquaintance, even friendship with your characters, influence the choice of the topic? Is it nostalgia for youth, when “the trees were big” and the feelings were vivid?

“In order to get to the depth, you must dig in one spot. We, modern people, are horribly shallow. The first thing that I do not like about our lives now is that nobody wants to be absorbed deeper into anything.

“We know nothing about ourselves. Not even about ourselves, because we never look inside our own depths. Let alone speculating about what is going on in your soul, I do not even know myself fully. I am afraid of this knowledge. Perhaps, only Russian classics like Dostoevsky and Tolstoy looked into their own secret depths.

“I will share a personal thing. At the very beginning of perestroika, the then editor-in-chief of Telekrytyka Natalia Lyhachova, who worked at the editorial office of Ukrainian Television back then, made a small story on me. She asked a question, ‘What do you like most of all?’ I said without a moment of hesitation, ‘Freedom.’ I don’t know why I answered like that. It seems, a woman should prefer love, creativity, children, but I said I loved freedom.

“Perhaps, this was an instinctive answer, because freedom is in my blood. My father’s ancestors lived in Putyvl povit in Chernihiv province. I even know two names of villages there – Vesele and Buryn. When in the 18th century, during the reign of Ekaterina II, serfdom reached its peak, people ran away. They settled in the remote forests near Kursk and Bryansk at the brook and lived almost like cavemen in order not to be slaves. In 1860s serfdom was abolished and the village, where my family is from, rebelled and did not agree to the conditions they were being offered. They had been rebelling for four years. Until a punitive expedition arrived. Everyone was whipped on a hill before the manor. However, one of my ancestors, Hryhorii Prymak, was not touched (even though he was one of the ringleaders), because he had donated a Holy Shroud to the local church. In those times, such deeds were respected. Even slaves were familiar with the concept of honor. However, he was sent to Siberia, where he died after two years. My father was a historian and he dug up this story.

“So, even though I am Russian according to my passport, I have Ukrainian ethnic roots. Moreover, I lived in Russia only until I was 17, and then I moved to Kyiv. This is my second home. I do care about what is going on in Ukraine today. I am really interested in what ‘freedom’ is, whether it has boundaries, and if so, where they lie, when a person can afford to be free, and when he or she cannot.

“Why I find the experience of the Sixtiers priceless and why I respect these people? Because I am convinced that freedom is an aristocratic rather than democratic category. I even doubt whether this opinion should be voiced, many find it offensive. But I think it is true.”

“PARAJANOV PLAYED HIS ROLE ‘IN THE THEATER OF LIGHT’ TO THE END”

The names of Secret Freedom characters are the following: Ivan Mykolaichuk, Mykola Mashchenko, Sergei Parajanov, Leonid Osyka, Yurii Illienko, Mykhailo Belykov, Larysa Kadochnykova, Ivan Drach, Kostiantyn Stepankov, Kira Muratova, Roman Balaian, Mykola Rapai, Vadym Skuratovsky, Vilen Kaluta, Bohdan Stupka. Please, forgive me if I forgot someone. This is indeed the glory of Ukrainian culture, I mean it. In your opinion, which one of these talented people was the freest in the country called the Soviet Union?

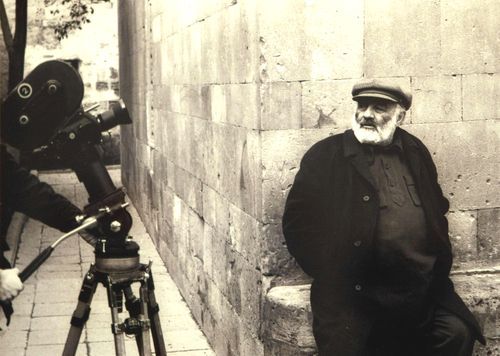

“I think it was Sergei Parajanov. You see, I view metaphysically any situation I analyze. So, each of my characters was given a test from above: how much they would be able to withstand. Oddly enough, Parajanov had a very complete personality. And he was also rather elusive: there were at least 25 personalities inside Parajanov!

“God sent him prison, but even there Parajanov played his role to the end. ‘A role in the theater of light,’ as Skovoroda would say. He lived in inhuman conditions, but he found an opportunity to make his dolls, create collages and scripts even in prison. And he came out a winner, a hero. For the world to lift him up, because he deserved it.

“Do you know what was the other reason (besides the facts that the leadership of the Ukrainian State Agency for Cinematography and the film’s directors were changing, and there was no financing) why it took so long to make this film? Secretly, I procrastinated, I wanted to ‘watch’ the fate of each of my characters till the end.

“The main idea in the script for me is the fate of freedom. The fate of Ukrainian freedom. But unfortunately, while I was immersing in the details of my characters’ lives and careers, we lost eight of them. Bohdan Stupka was the last to go. [Mykola Mashchenko, the ninth character of Secret Freedom, deceased after this interview. – Author.]

“I have to tell you that each one of those people built not only their life according to his own laws, but their death also. And they built them according to the laws of their own art. It was Parajanov who succeeded at this the most. With his usual artistic skill, he made a tragic attraction out of his death. One may think it is an exaggeration, but one day I heard Sofiko Chiaureli, who knew him closely, say an astonishing thing: ‘I did not understand, I never believed he was in agony, he went away while playing…’ Parajanov remembered who he was till the very end, he remembered the whole world watched him part with his life. And he finished playing, while overcoming the pain and suffering. He died just like he lived.

“The situation with Ivan Mykolaichuk was the most complicated. He was the weakest of my characters.”

And the closest to you in spirit, if I understand it right?

“Yes, of course he was. He was, and he still is.”

“MYKOLAICHUK WAS NO SAINT, BUT THERE WAS AN ASCETIC INSIDE HIM”

But why Mykolaichuk? Was he more talented than the others? Was there some kind of mystery to him? Was his talent the closest to your understanding of the essence of a Ukrainian actor and director? Perhaps, you have personal motives?

“Ivan and I met when I wrote once about him, an article for the magazine Soviet Screen. When we met, he kissed my hand, thanked, and said he was sure some Moscow critic wrote the article, because Ukrainian ones did not write in that style (laughs). For three days in a row, we met and talked, and talked, and talked again. However, I did not record anything: we had no dictaphones back then. Besides, I was afraid to break his trust and the absolute sincerity that emerged between us. You must agree that when a person talks when a recorder is on, they still correct themselves. I can ignore this gadget today only because you and me have known each other for a long time and understand each other well.

“During those three days, I developed empathy [understanding of the emotional state of another person through compassion and immersing in the person’s subjective world. – Author] with Mykolaichuk. It is as if you enter someone’s personal world, and let them inside you, start feeling them. That is why concentration and looking into depths is so important for me. You cannot understand a person until you have done that.

“I sensed Mykolaichuk at once. He was the only one of my characters who lived an active inner spiritual life. It was a constant process, hidden from outsiders. By the way, Larysa Kadochnykova said during an interview once: ‘Mykolaichuk was a very reserved person, he did not let anyone close, it was hard to communicate with him. He was even more reserved and complicated than Parajanov.

“Think about Parajanov. Oh, what an incredibly versatile personality he had! But he was Armenian, he played with this world, and God alone knew what was going on in his soul. But Mykolaichuk kept his distance. However, he let me into his world instantly, he trusted me with it. He said once, ‘Liusia, sometimes I think that you know me better than I know myself.’”

Were you on the first-name basis with Mykolaichuk?

“Yes, for almost 20 years, can you imagine that! We communicated a lot, visited each other, but still… We established a certain line that we never crossed. But it took one word for us to understand each other. Once, we stood near the Blue Room in the House of Cinema, and he said, ‘Liusia, look, but these are ghosts! This is illusion, they are not real…’ That is how Mykolaichuk perceived the cream of actors’ society. And cinematography… On the one hand, it attracted him, but on the other… He told me that when they had been shooting Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, he felt some kind of falseness: ‘It is one thing when you act in a theater, everything is relative there. But in a film you get close to nature, in the forest, with the birds singing around. And you start pretending and acting, and feel so ashamed!’

“I can talk about Mykolaichuk for hours and days. He was tender and very vulnerable. There is such type of people, humane. An artistic type. Mykolaichuk, of course, was an artist to the core. However, he had a philosophical spirit. His father was inclined to philosophy. And I completely associate Mykolaichuk with Hryhorii Skovoroda. Skovoroda was not only a philosopher, but also a poet, musician, traveling educator, a sower of good. It seems to me that if Mykolaichuk had been born in a different epoch, he could have easily traveled around to watch the world, think about it, sometimes sing or create something. He is wider and deeper than the actor’s profession.

“I do not quite understand what acting really is. It is histrionics. Bohdan Stupka was a brilliant histrionic. I quoted once, ‘The undead have no faces of their own, they wear masks.’ It is as if the actor does not exist in this world. It is not a bad thing. It is a special gift. I, for example, am completely devoid of it. It is even hard for me to play a critic’s role because I am not an analyst by nature. Perhaps, this is what I and Mykolaichuk had in common. I would also like to travel a lot, and be a bit of a courtesan and a bit of a nun (laughs). It would be nice to live in a convent and meditate, and then travel, and gather herbs. And then have a little fun in Madame de Pompadour’s style. This side of life is interesting for me too!

“This is the way Mykolaichuk was. He was no saint, but there was an ascetic inside him.”

I did not have a chance to get to know Mykolaichuk, but looking at his acting and directing works, it seems that even if he had a sense of humor, it was a hidden one, not obvious. He seems to be too serious to me, even somewhat “Western-Ukrainian-style” gloomy. Was it true?

“Oh, what about The Lost Letter? Heaven forbid! If Mykolaichuk was devoid of sense of humor, he would have never been able to shoot such a charming and witty film. One day I made an attempt at psychoanalysis and compared Mykolaichuk and Balaian: Ivan had a nocturnal consciousness while Roman, a diurnal one.

“Balaian is sober and realistic, and only occasionally one might catch a glimpse of a deep and ancient sorrow in his eyes, the kind typical for an anchorite in an Armenian monastery. Ivan was always profoundly serious, but sometimes he turned into a cheerful imp.”

“ILLIENKO IS THE MOST ‘DOSTOEVSKY’ AMONG UKRAINIAN DIRECTORS”

It seemed to me that equilibrium in stories about characters was not always observed in Secret Freedom. For example, you devoted significantly more time to Illienko and Lysenko than to Stupka. Is it a coincidence, or did you have reasons for that?

“This is true and false at the same time. What concerns Yurii Illienko, I was stunned by his death. Simply stunned. Because he, just like Parajanov, directed it. Then I read a book Dopovidna Apostolovi Petru (Report to Apostle Peter). And Illienko has become more interesting for me now than he was when he lived. I feel guilty because I had underestimated him. He resented me, and in general, he had reasons to. He knew his worth, and when Mazepa was out and he was invited to the radio station and asked who he wanted to talk to, he said: ‘To Liusia Lemesheva. I know, she does not accept everything in my film, but it is better to argue with a smart person, than listen to the chatter of a narrow-minded one.’ But I refused. Illienko would have defeated me hands down, I would not have been able to debate on equal terms with him.

“The sincerity of Illienko’s book touched me beyond words. At first I found it repulsive, so harsh, blunt, and sometimes cruel was his judgment of the others. But when I came to where Yurii was judging himself, I forgave him many things. He was so merciless to himself. I was astonished and could at last reconcile with him. I only wish I could have done it earlier.

“For me Illienko is the most ‘Dostoevsky’ among Ukrainian directors, and the most interesting in terms of analysis. By the way, Kira Muratova found the episodes with Illienko the best in my script, although Yurii himself felt hurt. He was a very prejudiced reader, he thought that in the script he appeared as a loser. But it is actually this diversity of his that makes him what he was as a whole.

“Speaking of Bohdan Stupka: in his last years he led such an intense life, worked with abandon, and plunged into everything he did. He burned the candle at both ends, and did it not for prizes or money. We gave him unfairly little attention in the film (now that it is ready we can speak about this) because all the footage with Stupka had been lost. Three-and-a-half-hour interview! Stupka was so sincere with us, and received our team so warmly. He was generous, considerate, spent seven hours of his precious time with us. But what is done cannot be undone.”

“AT THE OIFF I WAS ASKED TO MAKE A SEQUEL OF THE FILM, ABOUT ODESA’S CINEMATOGRAPHERS”

What kind of audience is Secret Freedom meant for? It is clear that the older generation will be nostalgic over their youth, friends they have lost, and all the good films that used to be made in Ukraine. The youth of today watch different films. Sadly, they won’t even know the names of many of your characters.

“I would like to give only one example. Last year our film participated in the Odesa International Film Festival. I was awfully jumpy. The cinema was packed full, there were a lot of young people too. They were very still during the film. I was so moved when after the show wonderful young men and women came to me to thank for the film. One young man from Odesa even asked me to make a sequel to the film, about the directors of the Odesa Film Studio. He regretted that only Kira Muratova was in the film while there were other great directors in Odesa. And another boy was astonished to see Larysa Kadochnykova there. He kept repeating embarrassedly, ‘If only I had known I was going to meet the live Marichka, I would have brought flowers along…’ I introduced him to Larysa, and she was flattered to see the sincere admiration of her young fan. So this is the answer to your question about Secret Freedom’s target audience.”

The Day’s FACT FILE

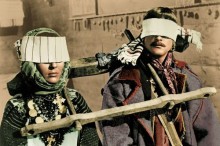

“PARAJANOV HAD A VERY COMPLETE PERSONALITY. AND HE WAS ALSO RATHER ELUSIVE: THERE WERE AT LEAST 25 PERSONALITIES INSIDE PARAJANOV!” / Photo replica by Ruslan KANIUKA, The Day

On September 4, 1965, Sergei Parajanov’s film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, based on Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky story, premiered at Ukraina movie theater in Kyiv. After the director’s speech Ivan Dziuba took the floor and informed the public about the recent secret arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals, giving the names of those arrested. The manager of the movie theater tried to push Dziuba away from the microphone, there were a few shouts “Lies!” from the public. Someone set the fire alarm. Then Viacheslav Chornovil shouted, “Rise those who are against tyranny!” A part of the audience stood up, but the film had already begun. In the interval Vasyl Stus supported the spontaneous protest: “Everyone should protest. Today they are arresting Ukrainians, but tomorrow they will come for Jews, and then for Russians!”

The protest action was not planned. The viewing, meant as a triumph of the official and internationally acknowledged Ukrainian culture (the film had already won the gold medal at the International Film Festival in Milan), turned out to be a spontaneous demonstration of protest. (From the materials of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group.)

Ivan Dziuba’s speech referred to the repression campaign which had been unleashed in Ukraine. With the end of Khrushchev’s “thaw” a part of young Ukrainian intellectuals (“the Sixtiers”) began to collaborate with the regime, and a part chose the path of opposition. The Ukrainian cultural and enlightenment movement was acquiring more and more political features: the Ukrainian samizdat (underground publishing) was distinctly oppositional in character, and emigrant publications were spreading fast. To nip head these off tendencies and defeat dissention as a social phenomenon, the secret police in Ukraine hastily carried out a series of arrests in early September 1965, putting more than 25 Ukrainian intellectuals behind bars.

News of the protest action in the movie theater spread like wildfire, and the “rally for publicity” in Moscow on December 5, 1965, protesting against the arrest of Andrei Siniavsky and Yulii Daniel, became the first public event to defend human rights in the USSR under Leonid Brezhnev. The authorities reacted immediately: Dziuba and Chornovil lost their jobs, Yurii Badzio and Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska were expelled from the Communist Party, and Stus from the postgraduate school.