The Day of the first performance, which coincided with the eve of St. Andrew’s Day, appeared to be symbolic, as one of the story lines touched upon a vision of Kyiv. But it is not the Christ follower that we see in the ballet, it is a priest of Perun, the pagan god.

The liberetto was written by Anatolii Tolstoukhov. Volodymyr Zubanov and Vasyl Turkevych built the performance’s plot based on images of the far past, little known but stirring up our imagination. There is a disproportion between the two different cultural doctrines of Ukrainian history. Behind the scene there is a vision of Kyiv as the new Jerusalem, blessed by God, the image of which became a cornerstone of the Christian development in the Slavic land, which also implies a common cultural space. Other facts became actual because of the military alliance between the Transdniestrian tribes and the Huns against the Roman Empire. That is how a strong leader and a noble warrior appears — one that created a solid foundation for the country. Kyi becomes this leader in the ballet. As the idea of the fraternal union is not developing, his brothers Shchek, Khoryv and sister Lybid are not mentioned in the ballet. Instead, Zoreslava (Olena Filipieva), his faithful friend, follows Kyi (Yan Vania), and they show up in the wreaths at the end.

In general, the authors of the libretto gave Ukrainian culture a unique artifact, namely a positive image of a statesman. The algorithm of this image does not correspond to the ancient perception of the statesmen. They are chosen by God, married to reign, and are fair judges. They are bellicose but noble guardians of the Fatherland. Actually, every scene is devoted to each of these traits. The first scene is about Perun’s kindness to Kyi, the second is about Kyi’s fair trial of the Huns and blessed heroic acts of war. In the third scene Kyi protects the humiliated Roman beauty Octavia (Kateryna Kukhar) and shows an example of real chivalry. And in the forth scene he realizes the boundless grief of his fellow tribesmen, who have to live on a devastated land. The Dnipro water, in which the tears of the little orphan dropped, strengthens the hero to serve the Fatherland.

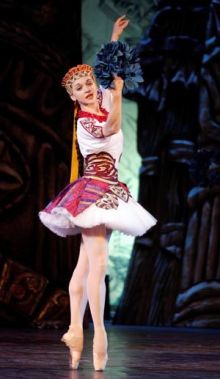

When choreographer Viktor Yaremenko took up the libretto he found himself in a complicated situation. There are so many opera masterpieces connected to the history of countries. But there are few ballets. Perhaps only Aram Khachaturian’s Spartak gained international recognition. How to solve this, since a libretto requires democratic, public, and plastique decisions, the conditions for which have not been present in academic ballet yet? The idea of “white ballet” was Yaremenko’s unexpected decision. The Slavic women, dressed in tutus under the sarafans and wearing pointes, nevertheless performed pas, fouette of sylphs and giselles in front of Perun’s idol. And Kyi impressed the public with the stunning lightness of his classic jumps. The ethnic color of the corps de ballet was more understandable — lifts and moves in the style of Soviet dancing collectives. But the most 20th century-like ballet was the Huns’ plastique language. Their wild dances reminded one of the modern staging of Borodin’s Polovtsian dances and Stravinsky’s early ballets.

Yevhen Stankovych’s music was the best part of the performance. Luckily, the main genre of the ballet was his main music topic — heroics, lyrics and self-affirmation. So the written music went far beyond the applied illustration. Here one could see a theater of timbres with its main characters, the leading timbres of the trumpets (heroics) and strings (lyrics). It seems that the ballet was not a story of Kyi’s valor but the foolishness of war and violence in any form. The Polans and Huns, described in the libretto as allies, were opposed as two hostile camps in Stankovych’s music. It reminds one of the Rusyns and Teutons in Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky. The vision of Kyiv is accompanied by the allusion to orthodox singing and illusory mellow chime.

Oleksandr Baklan, the conductor and director, almost managed a perfect orchestra performance. The tropical colorfulness of Stankovych’s music timbre contrasts was masterly played with love.