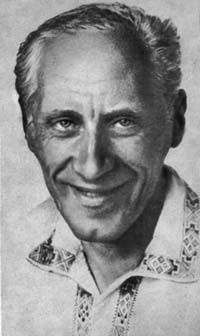

December 18 marked the 95th birth anniversary of the outstanding Ukrainian writer Yuriy Kosach (Jurij Kosacz). The life path of Lesia Ukrayinka’s nephew was studded with great frustrations, hopes, and grave mistakes. Having opted in his youth for exalted ideals and disobedience, Yuriy Kosach served a number of prison terms in Polish and German jails. Yet, in the twilight of his life, he was convinced that Ukraine should be part of the Soviet Union.

When Lesia Ukrayinka’s centennial was being celebrated, the writer, who had just arrived from the US, recalled the difficult period of the 1920s and 1930s, noting that in those years he had been close to nationalism but never belonged to any nationalist organization. But this is far from the truth.

THE END OF THE KOVEL UNDERGROUND

Late May 1932 marked the conclusion of the investigation into the case of the Kovel underground Ukrainian nationalist group headed by Lesia Ukrayinka’s nephew Yuriy Kosach. The following month the Volyn voivode’s counselor Stefan Vasylevsky finally proved to prosecutors that the Kovel underground fighters were members of the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO), i.e., terrorists, who deserved the harshest possible punishment. This occurred precisely two years before the Lviv underground fighters led by Stepan Bandera masterminded the assassination of Polish Interior Minister Bronislaw Pieracki.

A HISTORICAL REFERENCE

The Polish police uncovered the existence of the Kovel underground fighters in February 1931, when they arrested Yuriy Kosach, who was a law student at Warsaw University. The young writer was accused of nationalism, and his frequent visits to Kovel and contacts with local youth confirmed the police’s suspicions that a terrorist UVO group was based in this large railway junction. The underground worked under the guise of the so-called Cultural Society in which Yuriy Kosach was organizing local patriots.

The underground fighters would gather in Kovel, Kolodiazne, and nearby villages to study nationalist literature (Surma, Rozbudova natsiyi) that Kosach kept sending from Lviv and Warsaw. The underground nucleus was comprised of Volodymyr Markevych, Myroslav Onyshkevych, Pavlo Vitryk, Heorhiy Lisnevych, Zinoviy and Serhiy Somchynsky, Illia Kunytsia, and Illia Sydorsky.

In late 1931, when Yuriy Kosach informed the underground fighters that they would soon receive weapons, one of them, Yefrem Dmytruk, reported this to a village administrator named Pacholczuk. Arrests followed. Yuriy Kosach was taken to the Lutsk jail. As the police gathered evidence on the underground, a ring of irrefutable accusations relentlessly tightened around Yuriy.

A fellow student, Mykola Livytsky, the future president of the Ukrainian National Republic’s Government-in-exile for twenty years, managed to reduce the accusations against Kosach with the aid of his defense lawyer Samuel Pidhirsky, noting that Kosach was part of the Union of Ukrainian State Nationalists, which had organized a nationalist movement exclusively on Soviet Ukrainian territory. It was Mykola Livytsky himself who had instructed Yuriy Kosach to draw up a document entitled “Plan to Launch a National Movement in Volyn.”

Now that the shroud of secrecy has been lifted, the three bulky volumes comprising Yuriy Kosach’s case are now stored in the Volyn Oblast State Archives. Among other documents, they include excerpts from the above-mentioned plan.

“In the first period, conscientious nationalist militants will form the nucleus of a future organization of Volyn nationalists. The same nationalist militants will learn to wield greater influence by drafting as many educational and public-outreach platforms as possible and constantly propagating a nationally oriented ideology. This requires gradually setting up unofficial, for the time being, national societies aimed at spreading national ideas and drawing up a nation-oriented ideology and social superstructure, and, whenever possible, waging an active struggle.”

The underground showed undaunted courage. The 24-year-old Zinoviy Somchynsky testified in writing, “The Volyn land is not as calm as it seems to be. Although fate placed it in a God-forsaken place exposed to the winds and the Polish police, it has already seen the beginning of a sociopolitical movement.”

The members of the underground managed to organize only two groups whose membership was supposed to expand in the course of time. To ensure strict secrecy, the five members of one group were not allowed to know their counterparts in the other, and each of them pledged to form a group of his own and follow Yuriy Kosach’s instructions. Traitors were punished by death. The militants would camp in Kolodiazhne and on the banks of the river Turiya and bury prohibited literature in vegetable gardens or beneath barn floors. They maintained close contacts with the Lviv-based Sokil-Batko (Father Falcon) nationalist society.

After graduating from a Ukrainian lyceum in Lviv in 1927 and enrolling in Warsaw University’s Law School, Yuriy Kosach became an activist in the Union of Ukrainian State Nationalists headed by Mykola Livytsky. As the secretary of this organization, he propagated the idea of fighting the USSR to form an independent state in the Soviet-occupied lands. He recruited manpower for a legion that would eventually be sent to Soviet Ukraine. Kosach chose his native Volyn as the site of his activities. In August 1929, when the UVO became the OUN’s combat branch and Yuriy was visiting relatives in Kolodiazhne, he was approached by an envoy from the Prague-based nationalist leadership, who suggested that Kosach serve as general secretary of Volyn’s Ukrainian nationalists. Yuriy reportedly declined.

The members of the underground received light punishment: Vitryk and Somchynsky were sentenced to eighteen months, Kunytsia and Lisnevych to one year, and Yuriy Kosach to four years in prison. The Kovel underground ceased to exist. After the Lublin court of appeals passed down its final sentence in April 1933, Kosach escaped to Prague, after having been released on bail in the amount of 500 zloty paid by his mother.

ESCAPE FROM PRISON AND... FROM HIMSELF

In early May the young writer arrived in Prague. Even the numerous intercessions on the part of the distinguished scholar and professor of Warsaw University, Roman Smal- Stotsky, failed to protect Kosach from punishment. Kosach’s reputation as an “eternal revolutionary” and follower of Mykola Khvylovy, as well as notes discovered during a search, in which Yuriy said that young Ukrainians ought to streamline their chaotic activities and revive the spirit of the 1917 revolution, clearly did not work to the young writer’s advantage.

In Prague Yuriy Kosach worked in the archives and wrote prolifically. In 1934 the prestigious Ivan Franko Society of Writers and Journalists awarded Kosach second prize for a collection of poems entitled Cherlen, which was dedicated to Khvylovy, and for the novel The Sun Rises in Chyhyryn. (The first prize went to Ulas Samchuk for the first part of his trilogy Volyn and the third prize to Bohdan Ihor Antonych for his collection of poems Three Signet Rings). In addition to Cherlen, Yuriy Kosach wrote and published in exile A Moment with a Master (1936), Ariadne’s Thread (1937), Enchanting Ukraine (1937), and The Lady of Hlukhiv (1938).

Yuriy Kosach returned to Ukraine when it was under German occupation. He was arrested in Lviv, imprisoned, and then deported to Germany. The postwar years in Germany were quite fruitful for Kosach. Together with a group of like-minded writers, including Ivan Bahriany, Viktor Domontovych, and Yuriy Sherekh, he claimed that the current literary process in Ukraine was experiencing a profound crisis. In Germany he published the novel Aeneas and the Life of Others, which echoed his 1929 short story The End of Ataman Kozyr, about the frustration and spiritual drama of a Ukrainian nationalist. These works in fact prophesied Kosach’s further destiny.

Some time later, in the US, Yuriy Kosach changed his political views. He now saw nationalism as an evil and Soviet Ukraine as Elysium. In 1964 the writer was invited to the USSR to celebrate the 150th birth anniversary of Taras Shevchenko. After his return to the US, Kosach told Ukrayinski visti, “Ukraine is the country of the unchained Prometheus, who was punished for so many centuries for daring to equal the gods. Now Prometheus is free. The former plebeian, tramp, pariah, serf, and slave has become the ruler of his spirit: he builds cities, organizes regions and economic areas, plans, creates, commands, and leads the people forward and forward.” God only knows why the former champion of an independent and free Ukraine became a patriot of Soviet Ukraine, why he found himself in a very difficult situation, “setting [for himself] the goal of a life-and-death struggle against the so-called doctrine and people of nationalism, and being aware of the tremendous harm they do to the Ukrainian people.”

Yuriy Kosach made frequent visits to Soviet Ukraine, where he was a welcome guest of highly placed officials and well known writers. He adored Kyiv. He often said he was born in Kyiv, although archival documents say otherwise: Kosach was born in the village of Kolodiazhne, near Kovel in Volyn. But, after all, it is up to the writer to know where he was born, and this does not dwarf his heroic and simultaneously tragic figure. You feel it all the more acutely when you know that Kosach was not simply in love with life. He was a spiritual brother of Antonych, who wrote that he “was a beetle and fed off the cherries immortalized by Shevchenko.”

Despite this, Yuriy Kosach painted his surroundings in dark colors. The contemporary world often stood in the writer’s way, so he sought comfort in the past. This led him to write such historical prose works, such as The Sun Rises in Chyhyryn, Khmelnytsky’s Rubicon, and The Mistress of Pontis. In these comforting moments Yuriy Kosach created his most important short stories and novels. The writer died at the age of eighty in the US, an alien land.