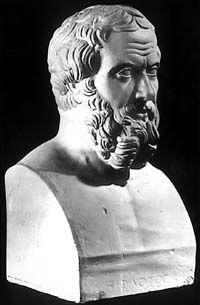

Herodotus of Halicarnassus, Asia Minor, who lived in the fifth century BC, is first of all known as the author of History, an immortal monument to human intellect. It is this Ancient Greek historian, writer, geographer, and ethnographer, quite aptly called the father of a long series of sciences, who produced, for the first time, a clear scholarly system of explaining his material. His research embraced a huge array of civilizations that existed at that time: Greece, Macedonia, Asia Minor and the Levant, Southern Italy, Thrace, Northern Africa, Egypt, Syria, Scythia, and the Black Sea coast (Pontus Euxinus).

As the system of geographic coordinates was not known in the times of Herodotus (approximately 484 to 430 BC), he describes Scythia using natural benchmarks, such as sea coasts and rivers, counting distances from and to them in stades (about 177 meters) or traveling days (about 36 km.) and along them in sailing days (Academician B. A. Rybakov claims this also is about 36 km).

Let us also note that N. I. Nadezhdin, for example, thus characterized Herodotus as a source of information, “Our Scythia, in comparison with other, far more interesting, countries of the globe, befell a happy lot to find precisely in Herodotus, the father of history, an excellent observer and drawer... One can say the picture of Scythia he drew is a rarest example of geographical fullness and finesse.”

Ancient Scythia comprised almost the whole territory of today’s Ukraine, sometimes even extending beyond. Herodotus informs /101/ (between the slashes are paragraph numbers of book 4 of Herodotus’ History) that the Scythian territory is a right square with sides 40,000 stades (about 710 km) long, two of which run from south to north, while its southeastern angle rests on the Kerch Peninsula. The square’s southwestern angle is the southeastern foot of the Carpathians, while its northern side goes from Kursk to Sarny along the rivers Seym and Uzh. The authenticity of Herodotus’ information has been confirmed with the archeological finds of Scythian culture, concentrated in this square.

Herodotus names eight most important Scythian rivers which, “starting from the sea, are navigable” /47/. All researchers identify the first four (from the west) and the last one with existing rivers: the Ister being the Danube, the Tyres being Dnister, the Hypanis Southern Buh, the Borysphenes the Dnipro, the Tanais the Northern Do nets and lower Don.

That it is impossible to identify the Panticapes, the Hypacyris, and the Gerros in terms of today’s geography can be explained either with Herodotus’s incorrect information or with the fact that the rivers, particularly the Dnipro, have essentially changed their course during the past 2500 years. As geologists cannot confirm this, researchers have been making efforts to “correct” Herodotus’ information. Accepting some of his information, rejecting and modifying other, they have created dozens of dissimilar geographies of Scythia.

The only thing they are unanimous in is nonacceptance of Herodotus’ claim that the Borysphenes, the main Scythian river in the northern land of Gerrus, bifurcates into two rivers, with one of these, still called Borysphenes, flowing south, confluent with the Hypanis (Southern Buh), and emptying into a lagoon south of Olvia /53/, and the other, called Gerros, running far east, blending with the Hypacyris and emptying into the sea near Cercinitis (now Yevpatoriya) /55, 56/. Moreover, it is in the habitat of the Borysphenites, three traveling days east of the Borysphenes (110 km), and further on until the Gerros, was the habitat of nomadic Scythians, that the Panticapes and the Hypacyris flow /18, 19/.

Herodotus has three indications about the whereabouts of the Gerrus land, where the Borysphenes bifurcates into two riverbeds: it takes 40 sailing days to reach it (more than 1400 km) from the north (from the Borysphenes’ source) /53/, the land of nomadic Scythians stretches from the mouth of the Hypacyris to the source of the Gerros and is 14 traveling days long (500 km) /19, 55, 56, 99/, there are graves of Scythian kings in the Gerrus land /71/ (according to Samokvasov et al., these are the Sulaside mounds, for the mounds near Nikopol date back to post- Herodotus times). All the three indications bring us to the area of Cherkasy. The Gerrus land is apparently situated opposite Cherkasy and enclosed in a triangle between the Dnipro, Sula, Seym, and Desna.

If one is to believe Herodotus to the end and accept this information, one will see no inner contradictions in his geography of Scythia. Still, there is a basic difference in the ways the rivers flow today. It follows from Herodotus’ description that the Borysphenes can only be identified with the Dnipro in its upper course, approximately as far as Cherkasy, while the lower Dnipro, flowing far eastward toward Dnipropetrovsk, can be identified with the Gerros. Moreover, the main western riverbed down which the Borysphenes flowed 2500 years ago no longer exists.

But the Borysphenes should have left a superficial trace in the shape of wide and deep valleys, which could not have possibly been formed by the present-day small rivers, and a dry valley crossing the Dnipro-Buh watershed. The Tiasmyn’s left tributary Irdyn is now the Dnipro system’s small river with a 1500 meter wide marshy valley. The valley along which the Borysphenes crossed the current watershed could have passed either between the Tiasmyn and the Greater Vys or between the Irdyn and the Rotten Tykych. Further on, the Borysphenes flowed down the bed of one of these rivers or that of the Syniukha as far as the confluence with the Southern Buh near the city of Pervomaisk. In addition, the Panticapes can be identified with the Inhul and the Hypakyris with the Inhulets. Now cut off from the sea by a more full-watered Dnipro, in ancient times it received the waters of the Gerros and flowed further south perhaps down the Kolonchak’s and Chatyrlyk’s beds until it emptied into the sea near Yevpatoria (modern archeologists claim the level of dry land in the area of Perekop was higher in those times).

The drawing shows a map of Scythia reconstructed according to Herodotus’ information. The map removes the apparent contradictions in Herodotus’ information, unambiguously tracing the dwelling areas of peoples and archeological cultures, but it seems incredible from the perspective of geology. Indeed, the Dnipro valley stretches several dozens of meters lower than the lowest segments of its watershed with the Buh under which, incidentally, lies the virtually unwashable crystalline rock.

But when one considers this an insurmountable obstacle, one does not take into account the fact that the glacier that was moving down the Dnipro bed left some water-pressure moraines, i.e., elevated areas which would block the riverbed and thus raise the water level in it by tens of meters. What has remained of one of those moraines is the Moshna Hora Cape near Cherkasy, which stretches 25 km. across and 90 m. above the Dnipro valley.

That the Borysphenes riverbed passed along what is now the Syniukha valley is indirectly proven by the latter river’s large width and depth, which is at variance with its water content, and by a crystalline rock chute-shape depression traceable down under. Only a sufficiently powerful and long-time flow could have washed through this depression. The unusual purity and transparency of Borysphenes waters, which Herodotus pointed out in comparison with the murky waters of other Scythian rivers /53/, could be caused by the fact that the former flew in a crystalline bed.

It is also known that the Dnipro Plateau is gradually rising, while the Dnipro Depression is lowering at the rate of one millimeter a year. This process caused the lowering of the eastern edge of the moraine wall that partitioned the Dnipro, as well as the rising of the water level in the natural reservoir that was formed after the Borysphenes bottom on the Dnipro Plateau had been raised. It was to cause the water, sooner or later, to overflow the moraine wall’s left edge, which began to erode at a catastrophically rapid pace due to its comparatively soft rock and an abrupt difference of heights in the flow. A mighty flow of water rushed down the Gerros, crossed the Hypacyris, and washed through a new riverbed down the stream which joined the Gerros with the Buh estuary.

This disaster, which changed the flow of rivers, could have occurred in the middle first millennium, between the reigns of Claudius Ptolemy (second century AD), who claimed Borysphenes flowed west of Olvia throughout its length, and Constantine Porphyrogenitus (tenth century AD), who was the first to mention the rapids on the present-day Dnipro bed. Perhaps, the words of Yaroslavna (The Lay of Ihor’s Host) “Oh, Dnipro-Slavutych! You have broken through the rocky mountains into the Polovtsian land” are a people’s memory echo of the above-described impressive event.