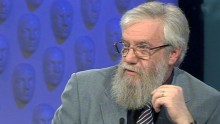

Mikhail Lotman is an Estonian scholar and politician and son of Yuri Lotman, who was the founder of the Tartu-Moscow Semiotic School and a prominent student of literature and culture.

Lotman Jr.’s research interests include general and cultural semiotics, the theory of the text and history of Russian literature. He serves as professor of semiotics and literary studies at Tallinn University and a member of the semiotics research team at the University of Tartu. Lotman was awarded the medal of the Order of the White Star on February 2, 2001. He has recently been active in politics and formerly served as a member of the Riigikogu (Estonian Parliament) on the list of the conservative party Res Publica. The scholar also served as chairman of the Tartu City Council and is a councilor currently.

Our conversation took place at the University of Tartu.

“IN EARLY CHILDHOOD, I WAS PREPARING FOR A CAREER IN… BANDITRY”

Was your choice of profession determined by your family history?

“It was not quite so. While young, I wanted to be a biologist at first, then a doctor. But in 1964, when I was in the 5th grade, I found myself in Leningrad just as the city celebrated the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare along with the entire Soviet Union. Productions of the Shakespeare Theater, which was on a tour in Leningrad at the time, and solo performances of the great actor John Gielgud made a big impression on me. I started writing plays and the book Drama and Theater in Shakespeare’s Age myself. However, another theatrical performance was being held in Leningrad at the time, I mean the trial of Joseph Brodsky, whose poems I read in manuscript copies in people’s notebooks and copied them myself. That is, they were singing glory to one poet and at the same time refusing to recognize poetry writing as a job and sending another poet to prison as a parasite. It made a strong impression on me and on return to Tartu, I switched to philology. You see, it happened so that in Tartu, with my family, I was more interested in science, and in Leningrad, far from family, I came to prefer philology.”

How did your father influence you in that regard?

“I and my brothers enjoyed a lot of freedom. My parents were terribly overworked at the university, doing much more than I do: I, for example, have only six hours of lectures a week, while they had over twenty, plus all the hours spent helping correspondence students, which time was not counted at all. They were at work from dawn to dusk. Therefore, in early childhood, I was preparing for a career in… banditry.”

Really?

“The whole culture thing sat poorly with me.”

How far were you able to advance in that field?

“I had to contend with some disadvantages. Firstly, I was very weak, though fought so fiercely that bigger boys did not want to fight me. Secondly, it turned out that I was a coward, which did not bode well for an aspiring bandit. I was afraid of heights and snakes. So, to tough myself up, I ran up and down construction scaffolding at night and joined a children’s zoological club to study snakes. I still jump from the tower sometimes to renew my un-fear of heights. In short, I turned out to be a mediocre bandit, although many of my childhood friends went on to serve long terms for various dishonorable acts.”

What is the most important thing your father taught you?

“If you believe that you are doing the right thing, it does not matter what others think. He cited an example. He served in the army in 1940-46 and went all the way to Berlin. There was mass panic in 1942, and panicking soldiers got encircled. He knew where to go because he had a compass, but soldier mobs came running in the opposite direction and shouting ‘we have been betrayed!’ and got directly in the way of enemy tanks. He wanted to run with them, because the herd instinct was already predominating, but he knew where he needed to go, and kept going. That kind of moral compass is very important. My parents and I had it switched on. Therefore, getting punched in one’s face did not seem so scary. I always chose the weaker side in a fight. Oh, how they beat me up! My nose configuration did not appear naturally. It was corrected by plastic surgeons on five or six occasions, I believe.”

“LIFE IS A TEXT THAT READS ITSELF”

What parts of the legacy of Yuri Lotman remain relevant now?

“Firstly, it is his major achievements in the history of literature. He found a lot of documents, and many things that he discovered in Alexander Pushkin’s work have become common knowledge. This is perhaps the most important thing in doing research. The analytical philosophy distinguishes between knowledge and opinion. Opinion is always personal. I have heard an opinion, and its source is important for me. With knowledge, it does not matter. When a personal achievement becomes part of knowledge, it is a mark of top-level research. My father succeeded in doing it, and not only in history, but also in literary theory, particularly in studies of the structure of the literary text, the semiotics of culture. Most of Lotman’s works have become common knowledge. For example, Brodsky did not like structuralism, because he believed that poetry was a living organism, not suitable for analysis. He began to teach in America then, and analyzed things in a very similar manner. His friend, the poet Lev Losev, remarked: ‘You criticized Lotman, but what you offer now is a simplified Lotmanian approach.’ He replied: ‘Perhaps this is the most natural and easiest way of analyzing text.’ I repeat, it has become common knowledge.”

The University of Tartu was famous for its semiotic school. How much has it changed by now?

“My father told me shortly before his death that science is like a snake – it sheds skin and keeps living. We should not cling to old ideas. Of course, much has changed. On a purely external level, our works are now published in English. It is related both to organizational issues and to the fact that we publish what is likely the world’s largest semiotic journal, and so must follow some rules. Internally, the most interesting developments have to do with biosemiotics.”

What is that?

“There are two directions in it, just like in semiotics as a whole. The first is an American one, and its founder was the eminent American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, while the second one is European and started with the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure’s work. Roughly speaking, Peirce was interested in how something becomes a sign, what are signs’ properties, their types etc. For Europeans, sign systems are more important than individual signs. In de Saussure’s thinking, a sign cannot function outside a system. The same is true in biosemiotics. The American school looks for signs we see in the animal world: how animals behave, communicate etc. The European school investigates what sign systems animals possess. Having attended a Soviet secondary school, we all remember Friedrich Engels’s definition that life is the mode of existence of protein bodies in an oxygen environment. It was not bad for the 19th century, although there are nonprotein and anaerobic forms of life as well. The belief that by synthesizing a protein one can create life appeared then as well. It turned out, however, that we cannot synthesize it without the DNA. What is the DNA? It is a certain set of information. Therefore, the protein synthesis itself is an information process, that is, a semiotic one. One of my colleagues once defined life as a text that reads itself. And since this is a text, the European biosemiotics uses my father’s tools to analyze it, to a large extent. Usually everything comes in the exactly opposite order, but here, cultural models are relevant for biological research even at the molecular level.”

“ANALYSIS AND LIKINGS SHOULD BE KEPT SEPARATE”

What are your research interests, by the way?

“Firstly, it is general semiotics. I am trying to develop a theory that would be relevant for any sign system. Secondly, I do research on literary semiotics, mainly poetry, common metrics, and also study the Russian literature of the early 19th and early 20th centuries. I am currently preparing a two-volume work on Pushkin. I have published a book about Osip Mandelstam and Boris Pasternak as well. As for Pushkin, I have been studying him for 40 years already.”

Is it hereditary? After all, your father wrote an excellent book about Pushkin...

“Our fields differ, since I focus on more technical things.”

What author do you like to analyze most of all?

“Analysis and likings should be kept separate. At the end of the Soviet period, when I was prevented from teaching and almost prevented from publishing for political reasons, I started to study film art. I spent almost a decade at it, but eventually I could not perceive it like a normal person. While people look at a film’s characters kissing, I analyze its background and lighting. This is the reason why I almost never write about living authors, for instance. By the way, it is the difference between a critic and a student of literature. A critic is like a doctor, while a student is like a pathologist. Anatomizing living people feels wrong. Therefore my favorites are authors of the early 19th and early 20th centuries, and also Brodsky. I wrote a book about him in Estonian.”

“ONE IS EITHER A POLITICIAN OR AN IDIOT”

What prompted you to enter politics?

“Estonia is a small country and everyone here has to do several things at once. I felt I needed to. Still, politics has never been the main occupation for me, even when I sat in parliament. I serve as a city councilor at the moment. Politics is not the domain where I want to make a career. I refuse various tempting offers now, not only administrative, but also political ones.”

So, why do you engage in it at all?

“It is most definitely not out of some personal ambition. Before entering politics, I was much more respected. Few people like politicians. I myself do not like them.”

However, you are still involved in it.

“We also do not really like wastewater treatment workers. But pardon my language, we still do not want to drown in shit. Someone has to do it. Should people be involved in politics in Ukraine? Was the Euromaidan a political event? Aristotle defined man as ‘a political animal.’ I here am a political animal. In fact, all of us are like that, just not all are aware of it. You are either a politician or an idiot in the classical Greek sense of the word – that is, a person who ignores politics. There were also ‘clients’ who were involved in politics, but only because they served their patrons who paid them to do so. You see, I am not an idiot and not a client. Yes, politics is a dirty thing, it is not an institute for noble maidens. The people is made of all of us. So you have to be involved, and you get dirty in the process.”

Since we have turned to present-day issues, let me ask you: is there the Russian-speaking minority issue in today’s Estonia? As you know, it has become the subject of very unpleasant political games in my country.

“This issue is always there. It is a different matter that unscrupulous politicians on both sides of the divide profit from it. For example, a journalist who had been fired for professional incompetence decided to lead the Russians in Estonia. Many failed figures do so – oh, we have a chance to get back on our feet, let us create a Russian party. All these Russian parties are very weak, but have good publicity in Russia, which covers it as follows: we have just met a prominent Estonian opposition politician.”

“I HAVE 12 GRANDCHILDREN AND A DOG”

Do you have any strength left for something other than work?

“I work in two universities. It can be said that politics is my hobby. Besides, I have five children and twelve grandchildren, whom I love to entertain very much. There is a dog as well. My son did me this (dis)service.”