The first publication on the oeuvre of graphic artist Mykola Kompanets came out almost three decades ago. Its author, poet Mykola Synhaivsky, wrote among other things: “Colors in his drawings are active and consonant with the word. Trees, clouds, the moon, and stars seem to be in motion and living their own natural unquiet life. So, you feel like talking to them, as you were a child…” Now Kompanets is a renowned master who recently celebrated his 75th birthday as Meritorious Art Personality of Ukraine, professor, winner of the Mykola Trublaini Literature Prize, recipient of two National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture gold and silver medals, whose oeuvre comprises hundreds of illustrations to Ukrainian classical literature, cycles of easel drawings, landscapes, as well as participation in solo and group art exhibits. He has been nominated for the Shevchenko Prize for the series “The Land of My Forefathers” and illustrations.

Mr. Kompanets, acquainting myself with your oeuvre in the past few years and art critics’ comments in the press, I found out that, characterizing your book graphics, some of them speak of an improvisation inherent in your style only. If I’m not mistaken, the Latin word “improvisus” means “unexpected” or “sudden.” Do you agree to this appraisal?

“Both yes and no. In my view, an artist who creates illustrations to a piece of literature cannot but improvise, aiming to supplement the literary text with pictures of the characters on paper. This applies not only to me, but also to all graphic artists who illustrate books. It is very important for an illustrator to feel the inner world of the writer to whom the literary masterpiece belongs. If he or she manages to do so, this will result in convincing and impressing graphics. I can remember a meeting with Mykhailo Stelmakh, a living classic of Ukrainian literature, who was pleasantly surprised to see my illustrations to his autobiographical novella Geese and Swans Are Flying. He was anxious to know how I felt his prose, for the drawings really ‘breathed with the truth,’ so to speak, and excited the reader’s imagination. This consonance, or harmony, between a literary text and a sequence of illustrations was achieved owing to the fact that we had all gone through the distress of the postwar hungry years and seen reconstruction of the Ukrainian cities and villages that were ruined when the Wehrmacht was seizing and the Red Army was liberating them. All this happened before our eyes and left a bitter imprint on our minds, which is expressed in both the word and the drawings in the black and white colors.”

I know that in the remote 1964 you decided to devote your art institute graduation project to Mykhailo Starytsky’s play Chasing Two Hares. The illustrations to this work were awarded a 3rd-degree diploma at the Ukrainian book competition. Six years later, art circles spoke of you as a gifted book graphic artist, when one of Gogol’s novellas with your illustrations came out. How did you manage to create colorful character types from a totally different epoch in those publications?

“Teaching graphics at the Academy of Arts, I hear sometimes from students that they have found an image to be illustrated. I begin to scrutinize what they depicted, and it looks unconvincing and somewhat superficial. By all accounts, the image begins to ‘play’ when the literary characters’ features and characteristic looks clearly remind you of the time period described in the book by the same author. This calls to my mind the picture A Girl in a T-Shirt by Aleksandr Samokhvalov, a well-known Soviet-era artist. This canvas was painted in the years of the so-called industrialization, and the heroine really personifies the crucial 1930s. She literally radiates youthful energy and unflagging optimism. This is the way the artist thought the future ‘builders of a new life” should look. The artist showed his talent in being able to portray an epoch in a usual portrait.”

And if we look still deeper into the past, we will see the people who later became literary heroes of Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Kotliarevsky, Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko, Taras Shevchenko, Lesia Ukrainka, Les Martovych, Ivan Nechui-Levytsky, and others. How did you manage to find typical traits in the characters who, generally speaking, saw the light of day 100 or 200 years ago but, thanks to you, have assumed concrete features in our time?

“I must have seen them the way our classics of Ukrainian literature saw them. For example, the author of the short story Granny Paraska and Granny Palazhka, which I illustrated, has a lot of satirical heroes. Their comicality can be easily conveyed by several means of expression. If a person is stingy, his or her lips must be thin. Thin legs are typical of a malicious person. A narrow forehead shows that the man lacks intellect, and so on. But the artist must also remember that it is very easy to go overboard, as the phrase goes. I don’t want to name some artists who, for example, depict a routine harvesting, where peasants wear festive embroidered shirts. This is a lie not to be put up with.”

Maybe, they insufficiently studied the material culture of Ukrainians?

“Undoubtedly, a painter or a graphic artist must know material culture in order to avoid such bloopers. But if an artist depicts plants in the picture, he does not need to be a botanist (smiles). It happens that just a hint is enough for an artist to realistically depict an object, while the spectator uses their imagination to see what is not on the paper or canvas at all.”

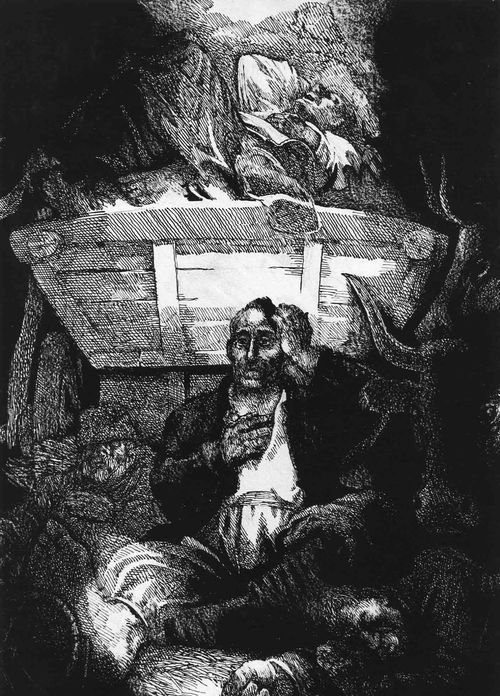

THE LOST LETTER, AN ILLUSTRATION TO GOGOL’S NOVELLA THE LOST LETTER. INDIA INK, PEN, PAINTBRUSH, 2009

Well, let us talk about your Gogol illustrations. This year the National Academy of Arts has nominated you for the Shevchenko Prize for a series of paintings, “The Land of My Forefathers,” as well as your illustrations to Nikolai Gogol’s works. Was it easy for you to carry out the latter project?

“It took me several decades in a row, with some intervals, to carry out this project. This was preceded by an event I’ll tell you about later. You see, any graphic artist who wants to illustrate a well known work by a no less known author must see the work of his predecessors. I mean the illustrators who have already illustrated, before you, the books with the works of, say, Nikolai Gogol. For this reason, taking up this extremely difficult job, I faced quite a challenge: to offer my own original interpretation of Gogol’s literary characters. For example, there was an artist, Yevgeny Kibrik, a wonderful painter and graphic artist (who came, incidentally, from Ukraine but departed this life in Moscow), who was acclaimed as illustrator of the globally-known oeuvres, such as Boris Godunov by Aleksandr Pushkin, Colas Breugnon by Romain Rolland, The Legend of Thyl Ulenspiegel and Lamme Goedzak by Charles de Coster, as well as Nikolai Gogol’s Taras Bulba. Kibrik’s illustrations to the latter proved to be so successful that they established a truly stereotypic image of this story’s heroes. So, I had to break myself for a long time to find an absolutely new vision of Gogolian characters.”

You succeeded, for when I leafed through illustrations to Gogol’s various works, I was so much stunned by them that I was terrified sometimes. You have an astonishing graphic work, Dead Bodies, one of the illustrations to Gogol’s novella A Terrible Vengeance, made with India ink, pen, and paintbrush. So, if a spectator looks fixedly at it, he or she can even have a sensation of infernality.

“It is no accident that Gogol was considered a mystic writer. Take, for instance, his Viy, a true horror story by today’s standards. Incidentally, illustrating his other literary masterpieces, particularly May Night, The Lost Letter, Christmas Eve, Sorochintsi Fair, A Terrible Vengeance, Tales of Rudy Panko the Bee-Keeper, and St. John’s Eve, I often thought I might be committing a sin by setting Gogolian demons free. But everything is material in this world – even evil.”

Do you think evil and art are compatible things?

“In the 1980s, fate brought me in contact with Rostyslav Lipatov, chief designer of the Molod publishing house, an extremely authoritative person in the publishing and artistic circles. For reasons unfathomable to me, he seriously quarreled with the artist Anatolii Bazylevych and instructed me, not him, to illustrate Gogol’s Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka. I then met Bazylevych on moral and ethic grounds to understand his attitude to this situation. I can remember him listening carefully and just saying in a friendly and even paternal manner: ‘Do this, brother…’ Bazylevych always respected me as an artist and, what is more, never had any complaints. But this story must have had its prehistory. In 1970 the fiction publishing house Dnipro put out Ivan Kotliarevsky’s famous book The Aeneid with fantastic illustrations by Bazylevych. The publication just created a furor in society. Bazylevych’s brilliant drawings somewhat resembled nails tightly driven into a structure that stunned you with solidity, reliability, and… hidden sarcasm. Many of his contemporaries later recognized themselves in the characters the graphic artist had masterly portrayed in The Aeneid. It also held a place for Lipatov (when the reader travels with Aeneas through hell). So, I sometimes wonder if it was one of the factors that gradually caused a conflict between Lipatov and Bazylevych.”

Apart from the abovementioned illustrations, your easel paintings from “The Land of My Forefathers” cycle are also participating in the National Prize competition. These are various-theme pictures made on paper with watercolors, colored India ink, and pastel. Most of them are the landscapes: Autumn and Spring Meet, Winter in the Carpathians, The First Snow, The Cherkasy Region: a Little Lake, A Carpathian Pattern, Mountains in the Woods, A Road in the Fog, and many others. What prompted you to realize yourself not only in book graphics, but also in graphic painting?

“It is perhaps the admiration that I, still a student, felt for the great French medieval painter Nicolas Poussin. His works were always distinguished for a geometrical precision of compositions and correlation of the color range. The paintings he made seem to be radiating the emotions of the author himself who, incidentally, was a virtuosic master of the paintbrush. But for me it was important to make a picture by means of a light touch – for example, to convey the quietness of nature and the presence in it of an individual capable of doing good only.”

And how did you manage to avoid a certain dependence on the art style of the outstanding artists of the past and keep your own manner of drawing intact?

“My art institute teachers were two talented masters: Heorhii Yakutovych and Hryhorii Havrylenko. They both made a colossal contribution to the development of national figurative art. I owe my artistic success, which I managed to achieve thanks to daily hard work, to both of them. And I began to notice in the last institute years that my student works elusively resembled the graphic works of Havrylenko. Aware of this, I had to make quite an effort to find my artistic identity or, in other words, individuality at last. And believe me this search lasted for more than one decade.”

If we sort of sum up what you have done in the national figurative art, do you feel that you are a happy man today?

“Undoubtedly, I am a happy man. For I can create new painting and graphic works, teach at the Academy of Arts, care about the people who are close to me, as well as dream that peace will sooner or later prevail in Ukraine, which is indispensable for our society to move toward the civilized Europe.”