All of us are familiar with the legendary names of epic heroes since childhood. Born of folk epics, they came to embody the intrepid defenders of our land against nomadic raids. The word bohatyr (epic hero) originates from the Turkic language, and was first mentioned in the Chronicles of Hypatius, in a story about Tatar voivodes in the years 1240, 1243, and 1263. The modern notion of bohatyr was known in the ancient Rus’ vernacular as khorobr, or khrabr in Old Church Slavonic, and was later transformed into what is still known in Ukrainian as khorobry, meaning brave. And so the word combination khorobry bohatyr is a tautology, like “buttery butter.”

Illya Muromets (Illya of Murom) is certainly a central figure in the epics about ancient Rus’ heroes and the subject of the greatest number of such bylyna (epic) stories. There are about 13 classical bylynas about him on record. Add here fairy tales and original Cossack songs, along with popular literary reworkings of stories about Illya Muromets. Many must be familiar with the feats performed by this popular epic hero. Few know that Illya Muromets was canonized by the Orthodox Church. His remains are kept in a glass sarcophagus in one of the caves of the Kyivan Cave Monastery, on a par with other Kyivan saints.

Our ancestors never doubted that Illya Muromets was an actual person, a warrior who served a Kyiv prince, later became a monk, and was later canonized. It is difficult to determine the veracity of this St. Illya. The Kyivan Cave Paterykon (Book of Saints’ Lives), which was compiled in the early 13th century, does not mention him. Illya Muromets was officially canonized in 1643, one of 69 saints in the Kyivan Cave Monastery. His earliest surviving image as a saint is an engraving from the mid-17th century. It may be that a totally different person was identified with the hero, although it is possible that the remains in the monastery cave are those of the prototype of this epic hero.

Traditional Russian historiography, including Soviet and post- Soviet, treats Illya Muromets as an embodiment of the Russian national spirit, particularly the Russian peasantry. The actual historical prototype was not a peasant, and even more interestingly, didn’t come from Murom.

The usual starting line peculiar to bylynas, when Illya enters the scene, reads: “Was it not from the city of Murom, from the village of Karacharovo...” seems to leave no doubt that the hero was from Murom, a Russian town, especially since Karacharovo still exists not far from Murom. However, historical data indicate that Illya Muromets was known in Southern Rus’ long before the first bylynas were recorded at the turn of the 19th century. The legendary hero’s name was first mentioned in 1547, in a letter from the Ukrainian magnate, Filon Kmyta Chornobylsky, to Ostafiy Volovych, castellan of Trotsk, in which he mentions the strength of “Ilia Muravlenin i Solowej Budimirowicz.” Kmyta was a starosta in Orsha, a town in the Great Lithuanian Duchy, bordering on Muscovy. His duties were onerous, as he had to collect intelligence about what was going on “in Muscovy” through scouts and spies, submit reports to the Polish king, and always had to be prepared to ward off enemy attacks. In his letter Kmyta complains about his sorry lot, the hunger and cold from which he suffers because of inadequate supplies resulting from the king’s lack of attention.

Kmyta recalls a scene in an epic about a hero by the name of Illya, one of the Kyiv prince’s host, and compares it to his own situation; just as Prince Volodymyr had to resort to the strength of Ilia Muravlenin and Solowej Budimirowicz [e.g., Illya Muromets and Nightingale the Robber], so will come the time when the king will also need their help. Another remarkable fact is that Filon Kmyta was related to Krzysztof Kmyta, a functionary from Chornobyl who in 1524, together with Senko Polozovych, took part in the formation of a detachment of Kyivan Cossacks, who would later carry out an attack on the Tatar horde on the island of Tavan.

Illya is next mentioned by Erich Lasotta. As an envoy of Austrian Emperor Rudolf II, he passed through Kyiv in 1594, on the way to the Zaporozhian Sich. His travel notes include an entry about what he saw at St. Sophia’s Cathedral: a richly decorated casket with the remains of a local hero: “In the second side chapel was the burial site of Elijah Morovlin (Morowlin), a noted hero, or bohatyr, as they called him; this burial site is now destroyed, but another one of his comrade in arms is intact and is in the same chapel.”

There is a noteworthy fact, namely that the oldest records of bylynas (17th century) mention “Illya Murovets.” Extant 18th-century manuscripts contain the most ancient prose retellings of bylynas about Illya Muromets and Nightingale the Robber. There are two redactions: the Sebezh version (in which Illya liberates the town of Sebezh on his way from Murom to Kyiv) and the Chernihiv (in which Chernihiv is liberated). All versions of the older Sebezh series appear to originate from one 17th- century source. A collection that appears to be the closest to the prototype identifies the hero as Illya Murovets, rather than Muromets, and as a resident of the town of Moriv. There are South Rus’ (Ukrainian) records of such epics. Finnish versions mention his last name as Muurovitza. There is an epic originating from the Don Cossacks about a hero by the name of Illya Murovich. A Spaniard named Castillo, who lived in Russia in the late 18th century, wrote about Ilia Murvits.

All this is proof that his ancient original last name was not Muromets but something like Muravlenin, Morovlin, Murovets. These variations ranging from the 16th to the late 18th centuries led researchers to study the names of various towns and localities in Kyivan Rus’. This study confirmed a number of names similar to Illya’s original surname. Thus, a populated area known as Muravytsia was located in the vicinity of the town of Dubno in Volyn oblast. However, most researchers attribute Illya’s last name to the ancient principality of Chernihiv, with the towns of Moroviysk and Karachev. This assumption fully corresponds to history: for more than 200 years, during the 11th- 13th centuries, Chernihiv challenged Kyiv in terms of political and military strength, wealth, and glory. The Chernihiv principality was the site of numerous armed clashes among Rus’ princes and with the Polovtsians. There is an epic describing the liberation of Chernihiv besieged by invaders, which is certainly an echo of actual historical events involving the name of this city.

Morovsk is the name of a town in Chernihiv oblast. The name is very reminiscent of the ancient Rus’ town of Moroviysk. The latter is first mentioned in chronicles dating from 1139 A.D. It was there that Prince Yaropolk of Kyiv entered into an alliance with Prince Vsevolod Olhovych. In 1152 Prince Iziaslav, en route to Chernihiv, which was under siege by Yuriy Dolgoruky and the Polovtsians, made a stopover in Moroviysk. Two years later, in 1154, Yuriy Dolgoruky did the same on his way to besieged Chernihiv. Prince Sviatoslav of Chernihiv, listing the cities under his jurisdiction in 1159, mentioned Moroviysk. Prince Sviatoslav Mstyslavych visited Moroviysk in 1160, and in 1175 Prince Oleh Sviatoslavych of Novhorod-Siversky, in a feud with Prince Sviatoslav Vsevolodovych, burned down Moroviysk.

The town of Karachev was on the border of the Chernihiv and Novhorod-Siversky principalities; it is first mentioned in the chronicles in 1146. In a feud between the Chernihiv princes, Sviatoslav Olhovych, bereft of all hope to hold his city, left for Karachev, attacked and plundered it, and went to join the Viatichians. After making peace sometime in 1155, Sviatoslav struck a barter deal and got back Karachev. Later the town went to Prince Sviatoslav Vsevolodovych of Kyiv (one of the heroes of the Lay of Ihor’s Campaign, and the town later served as a military base for the Kyivan princes in their struggle against the Polovtsians and Ryazan.

In the 19th century, V. F. Miller, a noted researcher of epics, called into question the alleged Murom-Karachev origins of Illya Muromets. He pointed to its absence in the most ancient recorded bylynas (in his opinion such epics were the ones without any mention of Illya’s Cossack status and where he is referred to as a brave young knight, not an old man). Commenting on Kmyta Chornobylsky’s letter, V. F. Miller noted that the author was a Lithuanian subject and thus an enemy of Muscovy, who was effectively protecting the Lithuanian border against Muscovite knightly people, so he could hardly regard Illya Muravlenin as a “peasant from the Russian city of Murom.” Therefore, referring to the oldest variations of the hero’s name, the researcher concluded that the surname of the famous epic hero Illya Muromets was originally not associated with the ancient Russian town of Murom, but a different locality. In his opinion, Murom in the epics was actually Moroviysk in the Chernihiv principality.

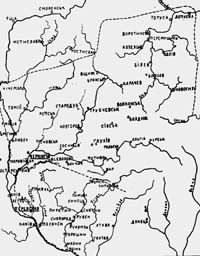

The proponents of the hero’s Murom origins (e.g., D. S. Likhachev, B. A. Rybakov, et al.) argue that the southern Rus’ city of Morovsk, en route from Chernihiv to Kyiv, doesn’t fit the epic pattern of that mysterious “town of Morov”; that the distance between Morovsk and Kyiv is too short to be glorified in the epics as one marked by heroic exploits; that the road from Murom to Kyiv, via Chernihiv, was more like it. However, a look at an ordinary map clearly shows that Murom, Karachev, Chernihiv, Moroviysk, and Kyiv are located roughly along the same line. In other words, the “straight road” from Murom mentioned in the epics would inevitably traverse Dev’iat Dubiv [Nine Oaks], a village in the vicinity of Karachev, where Nightingale the Robber had his lair. And so Illya Muromets had to fight him first because there was no way he could bypass “those Brynsk Forests” or cross the river Smorodynna before reaching Chernihiv. Legend has it, however, that Illya liberated Chernihiv first and afterwards set off in search of Nightingale the Robber.

Considering that Morovsk was part of the Chernihiv principality, it stands to reason that Illya should have served Chernihiv first and then offered his services to the prince of Kyiv. Proof of this is found in the bylyna text: his father and mother, granting his request to go to Kyiv, tell him he should travel through Chernihiv. According to another epic, Illya asks his father’s blessings to travel to Chernihiv, from where he would proceed to Kyiv to see Prince Volodymyr. In other words, there is no contradiction between the epics and the Karachev legends. Illya did leave his native town of Morovsk. Heading for Kyiv, he traveled through Chernihiv, where he fought Nightingale the Robber in the vicinity of Karachev, captured him and took him to Kyiv, where he was granted an audience with Grand Prince Volodymyr.

Historically speaking, the very expedition against Nightingale the Robber could have stemmed from Kyiv. Nightingale the Robber is an image of an epic hero, who was a representative of a tribe that the princes of Kyiv frequently had to fight. Legend has it that Nightingale the Robber had his lair on the straight, short road from Suzdal to Kyiv, which traversed a thickly wooded area, including vast marshlands. It is safe to assume that the Nightingale’s image is that of a hero originating from the Viatichian or other local Finno-Ugric tribes. The chronicles mention a number of campaigns undertaken by the Kyivan princes against the Viatichians. The year 966 witnessed Prince Sviatoslav’s victory over this tribe, which agreed to pay tribute. Prince Volodymyr of Kyiv embarked on a victorious campaign against them in 981. In 982, when the Viatichians rebelled, Prince Volodymyr attacked them and again defeated them. There must have been many such clashes, more than were recorded by chroniclers; they must have given rise to the image of a Viatichian epic hero living in the dense forest.

Illya Muromets vanquished Nightingale the Robber and cleared “the straight road,” which was of great historical importance and conforms to historical truth. Such straight roads (e.g., routes down the Dnipro, all the way to the Black Sea; down the Volga to the Caspian Sea) were usually seized by enemies — Khazars, Pechenegs, and Polovtsians in the 10th- 13th centuries, and by Volga and Crimean Tatars in the 13th-16th centuries. Cleansing these routes of robbing nightingales — highwaymen of all sorts-was an effort tantamount to a feat of arms and was glorified in epics. In other words, the legends are rooted in historical facts, like the expeditions against bandits (possibly also against fugitive serfs), which were ordered by the Kyivan and Chernihiv princes. As for Murom, this town about a thousand miles in a beeline from Kyiv, originally figured as a Finnic Murom tribal center in the epics.

There is another well substantiated version explaining Illya’s surname, which links him not with the Chernihiv period but directly with the Kyivan period of bohatyr activity. It should be remembered that the Kyivan cycle of epics about Prince Volodymyr the Beautiful Sun and his bohatyrs was composed precisely at the historical moment when the ancient Rus’ state was faced with the urgent challenge of protecting its borders. Confronted with the threat approaching from the Great Steppe, Kyiv above all had to block all enemy approaches routes. Prince Volodymyr switched from the policy of raiding rebellious neighboring peoples to that of planned defense construction around the city. In 988 the chronicler wrote: “Volodymyr said, ‘It’s not good to have a small number of towns in the vicinity of Kyiv.’ And he proceeded to build such towns along the banks of the rivers Desna and Ustria, Trubeshiv, Sula, and Stuhnia.” The borderland “cities” of the ancient Rus’ state were not cities in the contemporary meaning of the word. They were compact military settlements, originally built as primitive wooden fortresses or “castles” protected by palisades, known as zastavy — early warning outposts, so the prince could be informed in a timely manner about attack by nomads — and where residents of neighboring settlements could be offered shelter in desperate times.

It would be erroneous to assume that Prince Volodymyr personally erected such towns — i.e., that he personally supervised their construction. It stands to reason that such projects were entrusted to someone else, someone whose decency and diligence the prince could trust. Illya Muromets was such a man. “It was by the glorious city of Kyiv. On the knightly steppes stood a bohatyr’s outpost. The otaman of the outpost was Illya Muromets ...” These lines from the ancient Rus’ epic convey through the darkness of ages the contours of impregnable oak palisades and high fortified earthen walls, manned by knights, the bohatyrs, keenly gazing into the boundless steppe expanses. Thus, Illya could have received his last name, Muromets, not from a place name but from the fact that he erected defensive structures, fortified walls (known as mury in old Rus’) to protect Kyiv from attacks by nomads.

The image of Illya Muromets has undergone a significant evolution. Illya as a peasant’s son or Illya the Cossack are later images created in the 16th-17th centuries on Northern Russian soil. In reality, he must have been a Kyiv voivode or an officer of the prince’s host. That turbulent period left its mark on him, turning him into a “Cossack” and finally into a son of a peasant, according to legends that circulated in the Far North. During its long existence the image of Illya Muromets in the bylyna epos was expanded at the expense of other epic heroes, displacing them from other plots, and undoubtedly attracted a considerable number of migrating stories.