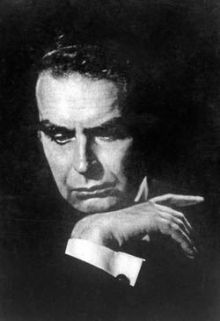

The musician Yuri Sozansky was born on March 4, 1926, in Grodno (now Belarus), but his personality was shaped by the family atmosphere and the aura of the Western Ukrainian city of Drohobych.

In his memoirs Pages from My Life Yuri Sozansky writes: “... you can write your own life story, then it will be a confession, or someone else can write it, in which case it will be a legend or a lampoon (depending on the author’s stand). I do not want a legend.”

He has lived in or visited Poland, Ukraine, Austria, Germany, Hungary, and Moldova. He spent seven years in a GULAG camp in what is now Turkmenistan. This was followed by years of study and creative work in the former USSR and Turkmenia.

Yuri Sozansky was a scion of an aristocratic family. His father, Polish army officer Stefan Sozanski nicknamed “Korczak de Worona,” was himself a descendant of the Austrian Baron von Turk, whose daughter Maria was his mother, while his father Ipolit Sozanski came from a family of Greek Catholic priests in Turka, which is in the Boiko land. Yuri’s mother, Mahdalyna Zhuk, was of Ukrainian descent and came from the Kossak family that gave Ukraine distinguished national liberation figures, such as Ukrainian Sich Riflemen [USS] Colonel Hryts Kossak and Zenon Kossak, a distinguished Ukrainian patriot who died fighting for the independence of Carpathian Ukraine. Yuri Sozansky’s parents got divorced, so his mother and grandmother played the main role in educating him and his younger sister Halia (Helena), as well as shaping their worldviews. They resided in Drohobych at the time. Music was always respected in the family. (Their mother was a soloist with the Drohobych Boian Choir.)

Sozansky has warm memories of the conductor, Mykhailo Ivanenko, who won at lottery and gave a considerable part of his prize to the Sozanskys, so they could buy a grand piano. After that Yuri and his sister began to practice playing it with great intensity. The celebrated musician Vasyl Barvinsky (this year marks his 120th anniversary, as earlier reported by The Day) noticed the boy’s talent and did not let him out of sight for many years. In 1941-44, he taught the young man himself.

There is a remarkable parallel in the lives of Sozansky, his mother, and his distinguished teacher: all three went through GULAG prison camps. Sozansky’s mother was arrested and was sentenced to seven years in prison simply because she was “a soloist with a bourgeois nationalist choir” — that same “Drohobych Boian” that was revived in present-day Ukraine and is upholding and adding to its predecessor’s creative legacy.

The following facts will clarify in what conditions the future professional musicians Yuri Sozansky and his sister were developing their talents. In his young years Sozansky already established himself as a promising pianist. After its “liberation” in 1939, Drohobych became a regional [oblast] center. A philharmonic society and a symphony orchestra were set up. In 1940, the young pianist (the boy was under 14 years of age) performed on stage with a splendid rendition of Franz Lizst’s “Hungarian Rhapsody” for piano and orchestra.

It would seem that new promising vistas were beginning to open for him, but the Second World War was already raging and Ukraine was about to find itself in its epicenter.

After the Germans came in 1941, Ukrainian institutions and associations were allowed to resume their activities. This enabled the young man to finish his studies at the gymnasium (high school) while continuing taking piano lessons from Prof. Barvinsky in Lviv and permorming as a soloist with the Boian choir. Sozansky’s practical experience was gradually complemented with knowledge in various domains of music.

After several years, another “liberation” was coming up. The previous one, in “Golden September,” left horrid memories: all things Ukrainian were banned, “proletarian culture” was imposed, and people involved in national-social activities were arrested and exiled. In the summer of 1944, Sozansky, then aged 18, faced a choice. He has three options of which two would entail terms in GULAG camps (where he, in fact, eventually found himself). These options were: (a) stay put and wait for Soviet troops to come; (b) go to the Carpathian Mountains. and join a Banderite partisan unit of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA); or (c) enlist in the SS Jugend and leave with the German troops that were retreating to the West.

This was a difficult choice for the young: ”I didn’t want to die or get crippled [fighting for] the [Soviet] Fatherland and Stalin; nor did I want to fight ‘on two fronts’ (as a member of the UPA).”

The Germans did not involve the SS Jugend in any combat operations. In fact, this organization was subordinated to the Luftwaffe, not the SS.

However, even the ten months he spent there were enough for the NKVD [to arrest him].

After travelling across Austria, Sozansky decided to return home. Americans brought him over to the Soviet [occupation] zone, where he was immediately drafted into the Red Army [and sent to a unit deployed in] Hungary. Further events followed in rapid succession: a trip to Odesa, ”friendly conversations” with NKVD men, arrest, investigation, and his verdict — seven years of penal camp labor on trumped-up charges of having taken training in an espionage school.

Sozansky writes in his memoirs: ”Our prison cell was packed with over a hundred men for the night. We could hardly breathe; we could neither stand nor lie down, and we did not have the strength left to stand on our feet the entire night.” Understandably, such a situation could easily result in arguments and bloody fights. Here is an eyewitness account: ‘Suddenly... we all heard words quietly sung in melodious Ukrainian: ‘Petro’ had started singing Sontse nyzenko and then continued singing all the arias from Kotliarevsky’s Natalka Poltavka. The cell became silent...”

Sozansky’s musical talents proved very helpful as he served his term. He was indispensable whenever the prison camp administration organized a ”cultural-educational” event. This system was well-balanced and reliable. Sozansky, like his mother and later his teacher, Prof. Barvinsky, had to sing glory to the Soviet Union as the world’s ”most beautiful and humane country” along and its leader Joseph Stalin. It was then that Yurii made new friends — among them Germans, Lithuanians, Jews, and Poles and created his first compositions.

Sozansky was released in 1954. In the early 1990s, along with tens of thousands of other innocent victims [of the Soviet regime], he was rehabilitated in a new independent Ukraine. Sozansky set about catching up with life: in less than two years he graduated from the Music College of Drohobych and got married. His wife, Frida Skorina, a music critic and teacher, had also suffered many losses caused by the totalitarian regime. Until her dying day she had remained a true, loving friend, and a reliable assistant to her gifted and restless husband. In addition to the piano, Sozansky tackled conducting, composing, and musicology.

Sozansky’s life path took him to Ivano-Frankivsk, where he headed the music drama theater as conductor and composer. After that there was the Donetsk Music Teacher Training Institute, where he conducted symphony orchestras, researched, and chaired a student research society. It was there that he came up with innovative ideas in the realm of musicology.

In between these two placements he studied at Kyiv’s Conservatory, where he also pursued a graduate course. There he launched fruitful cooperation in which he was guided by such noted scholars as N. Horiukhina, O. Schreer-Tkachenko and conductors N. Rakhlin and M. Kanershtein.

Inspired by the noted folklorist and his good friend Volodymyr Hoshovsky, Sozansky came up with innovative ideas for a philosophic concept of music as a special kind of metalanguage. While getting close to the development of a certain system in his studies, touching upon issues in semiotics, semantics, informatics, and structural analysis (which were banned at the time, just like cybernetics or genetics), Sozansky often delivered scholarly presentations, encouraged gifted students to conduct research, and wrote a number of papers on previously unresearched subjects. His accomplishments caught the attention of authoritative scholars in Moscow (V. Bobrovski, Ye. Nazaikinski, and V. Medushevski). Some of the Ukrainian scholar’s ideas which were innovative at the time were either borrowed or ruthlessly criticized, in the spirit of the times.

We can only imagine what kind turmoil Sozansky, a remarkable individual as he was, experienced in his heart. By then he was an acknowledged musician with considerable experience and attainments in various spheres. He conducted dozens of classical pieces performed by the symphony orchestras of the Kyiv Opera Studio and the Donetsk and Luhansk Philharmonic Societies. He composed pieces for specific instruments, soloists, and choir, as well as music for a number of plays. Testimony to his talent and masterful command of the technique are borne by the laudative reviews which were written by the music critic and composer L. Kaufman and have survived till our day. Sozansky also lectured and researched, and presented his view at scholarly conferences and in a number of fundamental articles. All this helps one grasp the tremendous scope of his activities.

Then there was the nervous breakdown, whereupon the musician decided to become a tractor driver, rebelling against [Soviet] mundanity and injustice. He completed a course in tractor driving and started to work in line with his new qualification. After his hand was maimed in an accident, Sozansky decided to leave Ukraine. In 1982, he found himself in Turkmenistan. There he made friends, built a new family, taught theoretical musical subjects at the Music College of Chardzhou, and immersed himself in educational and research activities.

Sozansky appeared in concerts in a piano duet with his second wife Valentina, conducted a symphony orchestra (for which he wrote new compositions), orchestrated classical pieces, and compiled a number of handbooks on methodology specifically designed for Turkmenia. Let me stress this particular aspect: Sozansky left his mark trace there, too, because he had a fluent command of a number of foreign languages and took an interest in the Turkic family of languages. As far as German is concerned, he authored the unparalleled essay “Translation of Gottfried van Swieten’s German Text of Joseph Haydn’s The Seasons (the Life of a Translation of a Religious Text in a Secular Oratorio).” Sozansky pointed to the inadequacy and inaccuracy of the existing translation of this famous work which, he argued, was caused by the ideological dogmas of the totalitarian regime.

For quite some time when he was far away from Ukraine, Sozansky maintained contact with relatives and friends. He kept in touch with his sister Halyna Sozansky-Klymkiv. She urged him to extend his creative legacy to Ukraine and he agreed. Gradually, he became known in his native land — in Western Ukraine anyway. Several years ago the students of the Drohobych Gymnasium who went there in the 1930s-1940s sent him a message of greetings on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of his birth. It includes the following reference to Drohobych:

“In May 2006, the Vasyl Barvinsky College of Music in Drohobych hosted a concert commemorating Yurii Sozansky’s 80th anniversary. The program was made up of his works that were performed by college professors and students. There was also the launch of the book Yurii Sozansky. Spohady. Materialy. Doslidzhennia (Yurii Sozansky: Recollections. Materials, Research), edited by Lilia Nazar, Ph.D. (Music). His fundamental study Muzychna semiotyka (Music Semiotics), also edited by Dr. Nazar, has appeared in print in 2008 and is likely to become a significant event in the realm of musicology of the past several years.”

Sozansky continues working for the benefit of his native-Ukrainian-culture. Residing far away from the land of his forefathers, he notes: “It is not hard to be Ukrainian if you speak Ukrainian; the challenge is to remain Ukrainian when you speak Russian.”