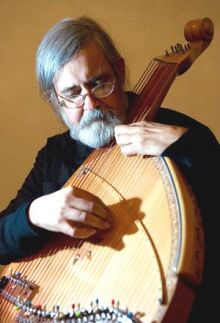

Julian Kytasty is a composer, singer, conductor, bandurist, kobzar, and flute player. He was born in 1958 in Detroit, USA. He graduated from the Montreal Conservatoire of the Concordia University in Canada, where he mastered composition and singing.

He learned to play bandura from his father Petro Kytasty, an active participant and assistant conductor of the Taras Shevchenko Ukrainian Bandurist Chorus. In 1980 Kytasty also became the art director of the New York Bandura School; he has also headed the ensembles Homin stepiv, New York Bandura Ensemble, and the avant-garde Experimental Bandura Trio.

He cooperates with Mariana Sadovsky, Alexis Kochan, Wu Man, and Michael Alpert. His students include Yuri Fedynsky, Mykhailo Andrec, and Roman Turovsky.

I took an advantage of Mr. Kytasty’s stay in Kyiv to meet with him and discuss the art of bandura.

I have a dilettante question: where does bandura come from?

“It emerged and was popular on the territory corresponding to the Cossack state, where Europe and Wild Fields steppe met. So, bandura combines in a paradoxical way both the European music traditions and the epic traditions of the Central Asia. Bandura is close to the idea of epic singing to the accompaniment of a music instrument, which is present in many cultures.”

Has there been a similar thing in human history?

“For example, one can visit the Metropolitan Museum in New York and see on the first floor in one of the rooms a small stone figurine of a blind singer accompanying himself on a string instrument, which was made thousands of years ago. The Museum’s Egyptian part contains the depiction of a procession along the Nile: a rich man is being carried on boats, and under a small roof a blind man with a string instrument is singing for him. These are really interesting points of contact of different cultures.”

Coming back to your personal history: why did you become a bandurist?

“I come from a family of professional bandurists. My grandfather and his brother Hryhorii Kytasty were members of the State Model Chorus in Kyiv back in the 1930s. There my father learned to play the bandura. During the occupation the remnants of the old prewar chorus started giving concerts in Kyiv’s environs in order to maintain their families and my father was accepted as a regular member of the choir at the age of 14 in order to save the populations from the force labor in Germany. The chorus miraculously survived the occupation and the war and after war found itself in the American zone in Germany, and immigrated to the US after all. The members of my family were active bandurists. They taught to students, my father conducted an ensemble, and my grandfather apart from being a bandura player, conducted the church chorus in Detroit as well. So, I was growing up in this surrounding. Frankly speaking, I resisted at first, but later I understood that I was hardly interested in dissolving in the American routine world, so I grasped the bandura as a thing around which I could develop my own self, I could say a word of my own in America.”

Actually, what does bandura mean for you?

“First and foremost, there should be understanding of what we mean by speaking about bandura. There is conservatoire bandura, which can be heard in big ensembles and orchestras on stage – it has few if anything common with the old-time bandura played by kobzars. There is a whole specter of transition instruments between them. For example, the instruments I was growing up with: there were several kinds of them. They were part of the professional school of the 1920s-1930s. Every musician creates his own style of playing them. Of course, I am being drawn to what I grew up with. Later I took up the kobzar bandura. I respect what is being performed in conservatoires, but I have little interest in this, because it does not appeal to me. I have tried to play the conservatoire instrument and though I have mastered it, I cannot force myself to give concerts with this instrument.”

What is closer to you personally?

“Namely kobzar’s bandura became the key to the instrument for me. In Ukraine there is a whole movement of people who are actively reviving it and trying to make such instruments and understand how to play them. In my opinion, this is a very interesting and needed movement. All this has almost been forgotten. Even my father’s generation, he and some bandura players, performed the historical repertoire, even dumas, already on the instruments and in the arrangements adapted to the concert stage of the 20th century. You could not hear anywhere samples of older performance. But when I started to play the old-time instrument, it revealed much to me. The principles of playing this instrument are very interesting. You can feel right away, where you can apply ornamentization, what possibilities the tonal system gives – not European major and minor, but other. The instrument sounds in quite a different way. One modern Japanese composer started writing music for old-time Japanese instruments, which have been so much forgotten, that there was no school of playing them. People asked him: ‘How do you come to creating music for these instruments?’ and he replied, ‘The instrument has a memory.’ I can for sure tell the same about bandura. It has a memory, it requires a special way of playing the sounds, it gives what it has the best, it tells in a very precise manner how one ought to play it. And then listening to the instruments one can create new music based on the principles of the instrument.”

Does the art of playing the bandura have a philosophical ground?

“It seems to me we hardly know everything about this old kobzar’s skill. The schools where blind people were taught were quite secret. It is known that the system of learning they had was similar to Oriental, specifically the Indian one, when the student accompanies his teacher in his travels and has to live for a specific period of time with him. There were oral books of kobzar’s art, which were transferred orally from person to person. The studies of this have started in Ukraine. I am waiting eagerly for every new studio of this kind. For me it is interesting to deeper understand what kind of thing it was, how one approached bandura, and then it will be possible to find out how to bring the deepest knowledge to the present day. Many interesting things can be created, based on this.”

A bandura or a kobzar player – what kind of heroes are they?

“I think it changes with time. Bandura was popular in Cossack environment. This is one thing. And another thing is the bandura players who were part of the nobility and starshynas’ milieu and performed for sole entertainment. But the accompanying instrument was also present in the epic tradition of blind musicians. This is a totally different thing. Say, in the traditions of the blind people we see the impressively emphasized religiousness. It is not quite church-type religiousness, although they did come to churchyards and had their own centers, but there was some philosophical and moralistic stream which did not quite originate from the church instructions. That was a very interesting phenomenon as well.”

You are speaking about epos, but this is the basic of art, epos existed even before the narration was divided into dialogues, before theater emerged.

“This is true, but Ukrainian dumas are a later version of epic poetry. I think they have changed very much in the environment of lyre players in the 19th century. This is where these moralistic motives come from. Besides, I am interested in the fact how easily one can read the dumas, which were popular in the repertoire of blind musician at the beginning of the 20th century when folklorists started to collect them. They are very concentrated and short for epic works. Cossack dumas have a trace of epic style, when there is a description of the hero’s clothes, what horse he’s mounting, but this feature is absent in kobzar’s dumas, and the core of the plot remains. The images are very general and universal: the widow from the duma about the widow and her three sons, sister and brother, Marusia Bohuslavka – there is a total concentration on this only character. With time these plots acquire many senses. What is, for example, Marusia Bohuslavka, about? On the superficial level the story tells about a captive woman who rescues other captives, but (an interesting moment) in the end she does not join the captives, but stays, because she does not feel that she can possibly reach the place where she grew up, she has changed, she will never come back, but she feels so deeply the sorrow of these captives that she takes a huge risk, releasing them. The Widow and Three Sons can also be interpreted in many senses, from purely family to national to ecological meaning. Strong archetypes have an effect here.”

We are speaking about archetypes, ancient things, but on the whole how conservative is bandura?

“It is possible to be radical in conservatism. I was mostly influenced by the recordings of Zynovii Shtokalko. He was born in Halychyna, Berezhany, in 1920. He was one of the first people to take up bandura seriously. During the war he also found himself in the camps for deported people and acquired medical education there. He gave concerts in the camps and won recognition specifically owing to the performance of the ancient repertoire. Not only was he a doctor, but also a researcher in his profession; besides, he published his avant-garde verse under the pseudonym Zynovii Berezhan. So, he was a person of his time. He was even turned out from the camps, as he was insufficiently politically conservative for that community. Having come to New York, Shtokalko worked as a doctor voluntarily, providing services for the underprivileged in Harlem. And from time to time, having equipped a studio in his apartment, he recorded what he mastered in playing bandura. He started from ancient pieces, because he knew the kobzars’ material much better than most of his contemporaries, and he was a real virtuoso. Quite naturally, after all he started to study the possibilities of the instrument. For the first time I heard from there how one can develop the tone system and ornamentization in music, which is absolutely modern, though it comes from ancient times. He recorded his instrumental improvisational experiments, which he called ‘Atonal etudes.’ He tried to develop an unusual tone system. What if one makes this note lower and this one – higher, what will be the sound? He managed to create the art of that time, mid-20th century, but it was based on the same instrument on which he performed the kobzars’ dumas, on the same methods he developed in dumas. I have always been drawn in the same direction.”

And what do you have in result?

“I start from making my own features on an ancient kobzar’s bandura or the one related to it. They allow you to play with both of your hands on all the strings, the facture is somewhat different than on the conservatoire instruments. I develop Shtokalko’s ideas. Currently I am working much on the improvisations in different tone systems in order to tune the instrument for many different harmonies, start in any of them and create this kind of music. I do this during concerts, without scores, in a purely improvisation approach. Besides, I always check myself on ancient pieces. I perform many different styles, including the music I grew up with and the works preserved by my father and grandfather. If it is an original thing, I have been having lately the programs in Shtokalko’s manner, some singing can intertwine. Sometimes I take an extract from a kobzar’s duma and can show it in more or less authentic form, or I can take fragments from various dumas and weave a single fabric of them. I am experienced in working with a music theater: I have for many years cooperated with the band Yara in New York. It is really interesting to meet and communicate on music topics with performers of other cultures. I have had joint projects with the musicians from Mongolia, Buryatia. I used to go on tours to Canadian festivals in the following ensemble: bandura, Chinese pipa, with two Hindu brothers – one was playing the modified guitar and his brother – the tablas. I have a joint recording with a Chinese musician, also pipa, she is a world-class performer. On the recording she is playing in a very interesting way the accompaniment to the ancient historical Cossack song in kobzar’s style. I take interest in avant-garde. New York has much improvisation avant-garde, various sounds.”

This city is an improvisation.

“Yes, and this is really inspiring. It is a great pleasure for me to take part in these events.”

Do you work with new media?

“In spring I created music in New York for the exhibits in the Ukrainian Home. On one floor the carpets were on display, and on the second floor – the work of Kharkiv avant-garde artist of the 1920s, Borys Kosariev. A young animation artist Mykhailo Shraha, whom I know from Yara, made an animation where carpets became alive and started moving. He took both separate ornaments from the carpets, and motives from Kosariev’s works, divided them into elements and these elements were moving on the monitor. He made a series of this kind of animations and I gathered a group of musicians who performed both improvisations and prepared pieces. As a result we had a whole program.”

When I listen to you, I get convinced once again that the most radical experiment is often turning to an older and simply forgotten tradition.

“You are absolutely right. This is more or less what I am trying to do.”

It seems to me you are not a typical bandura player.

“I am simply not afraid of new areas. I am not afraid because I feel deep connections with the instrument’s root. And the instrument does have a memory. I feel what I can do. I am not afraid of getting lost. It is interesting for me to see something new, to see to what extent it corresponds to the abilities of the instrument. Sometimes it is something which has never been performed on bandura, but it sounds good. The instrument seems to hint when something is wrong. This is my approach and I am not afraid of getting to a wrong place.”

In your opinion, what is the state of the bandura art in Ukraine today?

“I am acquainted with a lot many musicians and I really respect what they do. It seems to me the legacy of the Soviet time has not been quite overcome here. At that time they made something of bandura – as a result we have a somewhat interesting instrument and one can perform a plenty of things on it, but it is impossible to play the Cossack ancient songs. This connection was lost and it has not been completely restored. Moreover, one can feel that bandura players have little access to the deeper tradition or even not interested in it. But it seems a necessary thing to me. It should be part of the course. When a person takes up bandura s/her should understand well what kind of instrument it was 120 years ago, what kind of repertoire it had, how it was tuned, what one performed on it, what kind of technical methods there were. This is of critical importance for contemporary bandura players, even if they won’t be playing namely this kind of instrument. It is very important to restore the connection. I respect the works of professional bandura players who want to go further, do something interesting, perform jazz or blues. They are doing what is logical to their training. They were taught bandura, as it was a replacement for clavier, and they develop it in this direction. They find interesting things. In the same way I am interested in those who revive the ancient instrument even if they are not virtuosos. They make banduras themselves, recreate the old kobzar’s repertoire. Some of them discover kobza for themselves, others blind musicians’ lyre or torban. This world is being discovered bit by bit. I think this gap will soon be filled.”

My next question refers to Fellini. In his Repertoire of Orchestra instruments are compared to living creatures, animals. With what animal would you compare bandura?

“Every bandura has a temper of its own. Say, I can play the same note, the same sound on the old-time bandura, and it will reply in its manner, but I will get quite a different result on the factory-made bandura. It is a truly creature indeed, but it is itself. Banduras are my friends. Each of them has a face of its own. To play an instrument in a good way, you need to talk to it for a while. If I borrow someone’s instrument, I have to sit somewhere for a while and talk to it.”

As far as I understand you have a life-long dialogue with the instruments.

“Yes, because only in the course of a conversation it becomes clear what one can play on bandura. I know from my experience that it is dangerous to argue with bandura.”