This feature starts a series debating the teaching standard at Ukrainian schools in general and the instruction of literature in particular. Prof. Vira Aheyeva offers her views, which we believe are well-argumented and unbiased. The Editors would appreciate it if all those deciding to join the discussion placed the emphasis on the subject rather than emotions, for the subject is raising the educational standard in Ukraine for the benefit of our children. The Editors also hope that teachers and people at the Ministry of Education and Science will contribute their views. Please contact us at 2-L Marshal Tymoshenko St., Kyiv-212, Ukraine 04212; e-mail: master@day.kiev.ua

One of the innate shortcomings of the Soviet educational system, which we have still to overcome, was its stance that was antidemocratic and authoritarian in principle. The student was always regarded as a passive object, target of pedagogic efforts or experimentation. Ideally, that student had to sit up straight, quiet, and unblinkingly attentive through every academic hour, his hands neatly folded in front of him on the desk, if not writing down what the professor was reading from his own lecture notes. And the teacher was always right, a priori. Discarding such student- teacher relationships should have changed a great many of things in the curriculum and in the very school structure. As it is, we are changing a plus for a minus, one conjuncture of circumstances for the next.

Changing pluses for minuses is especially evident when analyzing the curricula, particularly the teaching of literature. One of the most difficult problems to be kept in mind when drawing up school courses in literature is that of canon. The Soviet gilded gallery of classics, either wearing vyshyvanka embroidered shirts or formal attire with prestigious government decorations, was always boring, and it is even more archaic now. An attempt was made to alter this canon on the wave-crest of euphoria in the early 1990s. Those who tried seemed to abide by those same principles of what was called patriotic education, except that Soviet patriotism was quickly replaced by Ukrainian. Paradoxically (or perhaps quite naturally), the most primitive texts were canonized. Of course, changing an ideological plus for a minus was much easier than taking into consideration the aesthetic values of writings or their readability in the student’s eyes.

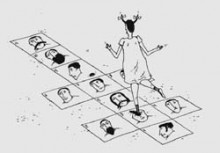

Once again, our schools are in a state of deep crisis, one of the reasons being the need to change the very model of student-teacher relations. The teacher will have to change his/her stance as Mr. or Ms. Know-it-all and learn to become a friendly interlocutor rather than a mentor hammering as much information into a pack of thick heads as absolutely possible. I realize that this sounds very like wishful thinking, but there is no other way to overcome the crisis. In order to change the model of the student- teacher relationship and the tasks to be solved by school, it is, of course, necessary to revise the curriculum. The shortcomings of current school literature courses are easy to list: overload (why torture the kids, making them draw endless chronological charts, learn writers’ birth/education/arrest dates by rote? Can’t they appreciate Nechui-Levytsky’s style by just reading his prose, without memorizing the dates and places?), too much emphasis on ideology, that accursed “patriotic education,” rather than on the aesthetic value of the text, asking oneself a simple question: Will the tenth grader find reading a given story or novel interesting?

We hear complaints about the younger generation being totally disinterested. We should not pay much attention. I think it is always interesting to watch the nuances of someone’s psychological experience, love affairs, intellectual conflicts, etc. In most cases reading epics about the sufferings of champions of a great cause is dull, especially if this narration is kept black-and-white, so the bad boys are always ugly and the good ones are handsome and squeaky clean. Nineteenth century epics with many pages describing scenic landscapes, with the river Rastavytsia, green willows, etc., left us yawning (and I suspect that our parents felt very much the same way). Naturally, our children are bored even more. Most poetry, not being based on the personal experiences and painful conflicts experienced by the reader, conveys no message. Sosiura’s poem Love Ukraine! (much as I respect the role the text played at the time) is about as topical or interesting today as Oleksandr Irvanets’s Love Oklahoma ! In many years of teaching I have never seen my class respond other than with ironical grins at hearing the line, “...my girl, a young man will never love you if you don’t love Ukraine...” And I consider this a healthy reaction. Thus, if the teacher continues to insist in class that a girl will never be loved by a boy if she doesn’t love Ukraine, the students will hate Ukrainian literature, regarding it (with their youthful maximalism) as idiotic. In other words, it is not worth including texts in the curriculum simply because they are ideologically useful. The student’s feelings must not be forced, just as the student must not be taught double standards. Doing so is more dangerous than the lesbian undercurrent (how dreadful!) in Olha Kobylianska’s Melancholic Waltz.

I think that more space should be allocated Shevchenko (of course, I don’t mean that gilded gallery portrait of Uncle Taras clad in a sheepskin coat, but an impassioned romantic poet whose verse is saturated with feelings and emotions), at the expense of the patriotic but not terribly talented verse by Hrinchenko (although there are WONDERFUL moments in his dictionary — Ed.). As it is, we teach our children classics, using mostly their worst manifestations. Lesia Ukrayinka considered her Boyarynia one of her worst dramas, yet our patriots quickly included it in the school curriculum, for it is perhaps the only text in which she voices her dislike of Russia. In fact, patriotism seems the only principle on which the curriculum is built. Once my son, a high school senior, came home with a dilemma. His teacher had said he could have his pick, learning Franko’s Eternal Revolutionary or It’s Not Yet Time... by rote. I had never lied to my son, so I told him both poems were among the worst in Franko’s legacy. I said he should choose the lesser of two evils — the shorter. Later, when he had to write a composition on Franko and we discussed his Faded Leaves, my rather skeptical teen looked apparently interested. Because the conflicts in one’s own quest for the meaning of life — those of love, betrayal, and suicidal tendencies — are invariably more captivating than authoritarian calls for smashing mountain rocks in the name of some goal and serving somebody. The ideology of serving one’s people is simply irrelevant now. You can explain it briefly in class as an historical fact, but you must not force your way into the students’ tender hearts and minds by urging them to join the ranks of the eternal revolutionaries.

Oksana Zabuzhko noted painfully once that Ukrainian romanticism should be studied the way one studies medicine. I would rather that some school literature programs were examined by a team of psychiatrists to diagnose their authors’ manifest masochism. It is time we stopped demonstrating to our children how much their country has suffered and what a miserable lot we all are. I can only think of masochism when trying to explain the fact that, of all the brilliant prose making up the Ukrainian artistic movement, our school programs include works by the least spectacular writers Ivan Bahriany and Ulas Samchuk. Their neopopulist stance and archaic style were criticized by modernists Kosach and Domontovych in the late forties. So why select them rather than Domontovych’s biographical Kulish Novels (I mean novels about women, not the Ukrainian people) or Kosach’s interesting historical stories?

Students say that Honchar’s Standard Bearers is still in some school programs. I know that schoolteachers are paid a pittance and they are not eager to read new books, but telling class about Vorontsov and Bryansky’s “liberation mission” in Europe is going a bit too far. After all, raising “soldiers of the (socialist) Fatherland” would seem no longer to be on the school agenda.

Summing it all up, I would like to emphasize several points. Our schools badly need a new program on literature. It has to be based on the principles of aesthetic value of literary works and their being understandable to a given age group. It is time to discard the ideological function of literature as previously imposed. Our literature must not teach the reader to love his Fatherland, army, political leaders, heroes, and so on. We must discard the principle of historical completeness. If a student, on finishing school, appears not have read anything by Hrinchenko, this is no tragedy. The students must be taught to read literature — in other words, to be able to interpret the text, discuss their impressions in class, rather than memorize and regurgitate what the teacher dishes them out. What kind of message was the author trying to convey? This is a question most frequently posed by the teacher. It remains unanswered. We do not know, and it is not really important. The text is reborn every time it is read and the reader is a co-author, rather than an infantile consumer that has to be taught clever things by the sage author. Also, it would do a world of good to discard epics serving as life stories of long-suffering writers. Let us face it. A delicately related story about Ivan Franko’s affair with Olha Roshkevych would be much more helpful for the students in understanding Faded Leaves and feeling a degree of empathy than some call to become an eternal revolutionary. Without rediscovering America, it is worth leafing through Polish or other foreign literature textbooks. Natalia Yakovenko, a brilliant researcher of Ukrainian history, said in an interview that history should stop being a boring schoolmistress and become an intellectual lady. The history of literature would also benefit from this metamorphosis. At least the students would no longer leave the classroom convinced that literature is specially included in the curriculum as an instrument of torture. Perhaps they would have fewer texts and chronological charts to work on, but they would have considerable reading experience, an experience in empathy with some psychological problems; they would know a truly talent work from a rag with false calls and teachings. Literature has never taught anyone to solve any sociopolitical problems. It can teach one and one thing only: an understanding of beauty.