The very stage name of hers – Olenka Gerdan-Zaklynska – is melodious and semantically rich. The first part of it, which was sometimes used personally as the author’s artistic pseudo, was her associative and ethno-cultural identifier, while the second derived from the surname of her father, a well-known and respected Galician teacher Bohdan Zaklynsky. She was born on April 14, 1916, in the Hutsul town of Zhabie (now Verkhovyna). Her father’s occupation caused the family to often move to the neighboring and Transcarpathian villages (Poroshkiv, Velyky Bychkiv, Yasinia), which enhanced the emotional impressions of Olenka, her sister Orysia and brother Sviatoslav. “I began to dance as a child,” the reminisced later. “Any manifestations of movement always attracted me unspeakably.”

ASPIRING TO “DANCE IN ORDER TO LIVE”

Years went by only to increase her desire to “dance in order to live” (paraphrasing the maxim of her idol Isadora Duncan “To dance is to live”). Although father took a dim view of her stage career and encouraged her to compose poems (which also became part of Olenka’s artistic essence), she managed to receive a proper artistic education in her childhood and youth.

She heard the first applause to her dancing talent in the late 1920s in Prague, where she went to a Ukrainian high school. The girl did further dancing studies contrary to her father’s will. In Podebrady, near Prague, she attended classes conducted by Vasyl Avremenko, a young reformer of the Ukrainian national dance and, later, took lessons from Oleksandr Kostin, a Ukrainian classical ballet master who ran his own school in Prague. At the same time, also in Podebrady, she debuted as ballet soloist. He continued to gain secondary education at the Ukrainian Girls Institute in Przemysl. “School duties prevented Olenka from doing separate dancing studies, but still she performed solo and group dances that were always a star attraction of school soirees,” wrote Maria Pasternak, a well-known researcher of choreographic art, according to the dancer’s words. But it was not before she moved to Lviv that Olenka Zaklynska began to form systemic views on dance as modern art, which enabled her to discover the little-known esthetic and, hence, metaphysical space.

The musical Lviv of the 1920s-1930s saw the rising popularity of innovative trends in reforming the classical dance in a modern key. Like the entire Europe, this place favored the system of the prominent Swiss composer and teacher Emile Jacques-Dalcroze, the essence of which was synchronization of the musical theme with the rhythmic and plastic data of the performer as bearer of the main genetic rhythm code.

No lesser interest was also shown in the experience of performing the so-called expressive dance by the German dancer and choreographer Mary Wigman, a pupil of Jacques-Dalcroze. Zaklynska also studied for three years the modern artistic dance of Maryna Broniewska and Oxana Fedak-Drogomyrecka, the pupils and followers of the outstanding European innovators who conducted their schools at the Lviv-based Mykola Lysenko Music Institute. Concurrently, Zaklynska learned music-related subjects from Roman Savytsky and Mykola Kolessa, who helped the talented girl systemize her views on Ukrainian folklore and music tradition.

One of Olenka’s mentors, Oxana Fedak-Drogomyrecka, had studied Jacques-Dalcroze’s principles at his institute for three years. She not only properly understood the subtleties of Dalcroze’s dancing methods, but also correctly adapted them to Lviv recipients, applying educational exercises and “sample dances” to folk music and work of Ukrainian composers, such as N. Nyzhankivsky, V. Barvinsky, and M. Kolessa. As it eventually turned out, this was of paramount importance for the formation of the artistic individuality of Zaklynska and some other female students of the school.

But Olenka, who was eager to learn the new possibilities of modern “rhythmoplastique” (this term was rather widely used in Lviv in the 1930s), also evinced no lesser interest in Wigman’s esthetics of dancing which the Lviv-based Maryna Broniewska had borrowed directly from the authoress herself. The very emotional nature of Zaklynska gravitated to expressiveness. She showed interest in the techniques of the “expressive dance” which allowed one to express his or he innermost feelings though movement.

It is the esthetic syncretism of rhythmoplastique and expressionism that let the young dancer form an individual manner of the “creative dance.”

Rhythm was a subject of conversations in many art milieus of Europe in the 1930s. But Zaklynska, who was very young at the time, could not know all the subtleties of this new trend in the development of choreography. Rather, she could know about these problems thanks to her exceptional intuition. She spent her time not only attending lectures and training sessions in Lviv, but also in traveling across the Hutsul area, Boikivshchyna, and Lemkivshchyna, and, to quote her, she “caught everywhere the rhythm that moves our people in a lively dance.” For this reason, her Lviv studies of the dancing art, improvisation, and composition were taking a shape in line with the Ukrainian ethno-cultural tradition.

The first peak in Olenka Zaklynska’s performing art, as a result of a well-considered strategy of search, were the dances “Road” (to the music of Z. Lyska), “Blizzard” (to the music of V. Barvinsky), and “Remembering the Mountains” (to the music of V. Bezkorovainy). She worked on them when she had already successfully shown Lviv audiences her “Dribushka,” but – from 1936 until the triumphal 1938 – she had to go down a very difficult road of self-improvement that included perfecting rhythm and plastique details. No sources have ever described the way it was done, but she was working as hard as she could for the 1938 International Festival of Artistic Dance in Brussels. She considered it her task to articulate as much as possible an ethnic image of the dancing themes, where Dalcroze’s principles were supposed to help her disclose the spirit of the Ukrainian intellectual and cultural tradition. She brought four themes to the festival – “Dribushka,” “Road,” “Blizzard,” and “Lullaby.”

Very fragmentary information about the participation of a highly-talented Ukrainian woman in a prestigious art festival includes evidence of the numerous obstacles that she had to overcome on the eve of it. This may have been the cause of her coming late for the beginning of the competition, but this was soon forgotten. Olenka Zaklynska won in her nomination.

“It was not only a matter of her personal success, but also a question of all-Ukrainian importance, for she acted as a Ukrainian who performed her own dances to the music of Ukrainian composers. This event was one of the brightest moments in her dancing career, for it paved Olenka the way to the art world at large. Indeed, she became Western Ukraine’s most popular Ukrainian stage dancer,” said the abovementioned Maria Pasternak.

VIENNA, INNSBRUCK

Olenka Zaklynska’s program, which was mapped up “to allow for artistic growth,” seemed to be predetermined by political events. The Soviet authorities, which radically restructured Lviv’s cultural and artistic life in late 1939, did not understand or need this art of rhythm and plastique. Only in 1941, when the Lviv Opera House was formed, Olenka became part of its ballet troupe. Olenka continued to actively use the experience she gained in the theater, especially some of its elements, even though the dancer never regarded the academic genre of ballet as a goal for her further development.

As the war was drawing to a close and the front line was approaching, she left Lviv for Vienna. She joined there another European-caliber star – Rosalia Chladek – who had reached the acme of glory by that time. “She is the creator of her own dancing method based on expression,” Zaklynska explained later. “In her view, movement should come out of a point on the human body’s axis. It is from there that arms beam in all the sides.”

At the time, Chladek, director of the Vienna Conservatoire’s educational center, was also doing choreographic work for the National Theater. Her teaching system consisted in establishing the physical principles of movement on the basis of the human body’s individual anatomical particularities, which made it possible to differentiate the rhythm structure in order to fulfill certain tasks in a dance. The popular dancer experimented a lot with stage production forms. In this atmosphere, in collaboration with Chladek, Zaklynska created her own composition, “Roman Fountain,” which she liked to show later at her soirees.

But she could no longer stay in Vienna. After the end of World War II, by force of her political status as a Ukrainian, Zaklynska shared the destiny of the tens of thousands of “displaced persons” in special camps set up in Austria and Germany. In one of them, on the outskirts of Innsbruck, Olenka regained the spirit of the mountains, recalling her native Carpathians and overcoming a lot of psychological and everyday-life difficulties. There is a little old photo, which shows her dancing “Dribushka” to the music of Kolessa against the backdrop of the high Alps. “Happy” is just the right word to describe her smile and emotional condition.

Newspaper articles of that difficult period portray her in several different images – as dancer, school teacher, and even co-organizer of a Ukrainian art exhibition. In early January 1948 she took part in a concert at the Innsbruck City Theater, which included representatives of different national groups of the “displaced persons.” “A Hutsul Girl,” “Joy,” “Golden Dream” – these dances filled Zaklynska’s repertoire in the far from happy conditions of the Innsbruck camp for the interned.

CANADA: YEARS OF THE MOST VALUABLE EXPERIENCE

Also in 1948, she moves to Canada and first settles in Winnipeg, where she sets up her own school of the Ukrainian dance as part of the Higher Educational Courses. A little later, Zaklynska, who has also assumed the stage name of Gerdan, wins a diploma and the first prize for a solo and a duo dance at the 1st Festival of the Ukrainian Dance and Music. Very soon, her school pupils received five awards at a Toronto festival for dancing “Dumky-Kolomyiky” and “Hopak” that she had staged. Then this company took part in a number of productions by Ukrainian-born Canadians and even went on a tour of big US cities. At that period, Olenka Gerdan-Zaklynska staged some of her own image-based choreographic works. One of them was “Glory to Ukraine” which had a success on the stages of Toronto’s Ukrainian theaters. From 1950 onwards, she continued her teaching career in Toronto, where she had her own school of artistic dance at the Institute of Music.

It is astonishing how quickly and, as it seems, painlessly the young dancer – she was only 32-35 years old – managed to adapt to totally new everyday-life and psychological realities. Olenka flew in the face of any difficulties thanks to the power of her talent and self-denying service to art, ignoring elementary personal life requirements.

She had no time to sing the blues. Very seldom did the motifs of loneliness penetrate her poetry or painting which she began to practice at the time. Instead, dancing absorbed the whole range of feelings and personal sufferings of a seemingly happy and successful artist. The early 1950s saw the shaping of some important creative and methodological ideas of Olenka Gerdan as a dancer, teacher, and theoretician of dance. After some time, these fragmented ideas formed the basis of her essay Art, Artist, and Artwork.

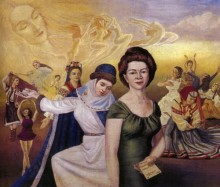

The mature judgments and precise description of the complex esthetic and spiritual nature of art could not remain unnoticed by those who were not indifferent to artist’s wonderful talent. For example, in July 1954 Gerdan-Zaklynska enters (together with U. Samchuk, M. Golynsky, M. Dmytrenko, O. Tarnavsky, et al) the organizing committee of the First Meeting of the Ukrainian Artists in the US and Canada with the Public held under the slogan “Ukrainian Artists Protest against the Destruction of Ukrainian Culture by Moscow” in Toronto, Canada. That was the most high-profile review of the worldwide Ukrainian community’s national cultural forces after Word War II. For this forum, Olenka prepared a new esthetic “passport” of herself as a universal artistic personality, which synthesized her exceptional outer beauty, the gracious movement of her body, the idea of a stage costume that she designed, in the minutest details, on her own, and, after all, the performance of a genius.

Indeed, those years, extremely intensive in terms of artistic discoveries, gave her the most valuable experience. Intuition and vocation, as well as national awareness deeply rooted in her artistic outlook, led her to new stage images of the “expressive dance” or her personal “creations” (a genre-defining term in the vocabulary of choreography). The highest-raking from this angle is the composition “Yaroslavna’s Lament” to the music of Mylola Lysenko – another peak in Gerdan-Zaklynsky’s art life story.

“In this picture, we found a response to our subconscious longing for an ideal superman,” O. Rudnytsky wrote. “Covered with the heroics of our princely era, the composition’s four figures are filled with sorrow, devotion, princely pride, and profound faith. The depth of artistic imagination, the logic of visible movements, the mimics, and the techniques of showing anxiety in the creation ‘Yaroslavna’s Lament’ only confirm the opinion that Olenka Gerdan can be considered the best choreographer and performer of the contemporary Ukrainian dance.”

NEW YORK: THE GREATEST SUCCESS

After a great success of the tour of her Winnipeg artistic dance school pupils in Canada and the US and her relocation to Toronto, where she conduced a rhythm and dance class at the Lysenlo Music Institute, Gerdan accepts the invitation to move to New York. She becomes a professor at the Ukrainian Music Institute in 1956.

The different rhythms of life mobilize her still more for public and cultural affairs. She becomes an active contributor to Svoboda, the diaspora’s biggest newspaper at the time, and collaborates with the women’s journal Nashe zhyttia. In New York, Olenka Gerdan signs up for the painting classes of the well-known artist Liubomyr Roman Kuzma, and takes an active part in art exhibits. Her pictures and graphic works usually visualized her memories of the native land, the Carpathians. The motifs of nature were of a subjective character in her expressive vision, with a somewhat sorrowful mood. Olenka Gerdan’s poetry had an equally rich intonational (“impressionist”) palette. The rhymed miniatures, which made up five cycles of the book Rhythms of Mountain Valleys (New York, 1964), are studded with her radiant metaphorical associations with childhood in Ukraine (“Singing Green,” “Highlands,” “Mountain Valleys,” “Thyme,” “Fragrance”). Besides, poetry allowed the author to reveal some of her very personal feelings, sometimes with dramatic intonations.

What was a burden on her soul fitted in, over and over again, with the tissue of her choreographic creations the number of which noticeably rose in this new, American, period of her artistic life. Among them are “Dumka-Kolomyika,” “Gagilky-Vesnianky,” “Shumka,” “Gypsy Love,” “Stratospheric Dance,” “The Present-Day Waltz,” “Riflemen’s Songs in Choreography,” “Gandzia,’ “Reminiscing the Mountains,” “The Wide Dnipro Roars and Moans,” “Lasso,” and others.

1961 was the peak year, as far as public impact of the dancer’s and choreographer’s outstanding talent is concerned. On April 30 New York hosted a ceremonial dance recital of Olenka Gerdan-Zaklynska under the auspices of the Initiatives and Honors Committee consisting of prominent artistic figures of the Ukrainian diaspora. According to reviews, this event, the biggest of its kind to honor the outstanding Ukrainian artiste, was on a high organizational level. On December 29 of the same year, the Ukrainian Literature and Art Club hosted a soiree in her honor, which heard Olenka personally recite her poems and the abovementioned essay Art, Artist, and Artwork.

Metaphors complicated the structure of the language of Olenka Gerdan’s choreographic creations of that period, on the one hand, but linked her as a dancer and choreographer more closely, in terms of concept, with the Ukrainian ethnic tradition, on the other. On June 1962 New York saw another high-profile choreographic production, “A Collection of Hahilky-Vesnianky,” performed by her pupils at the Ukrainian Music Institute’s school. Various cities of Canada and the United States considered it an honor to invite Gerdan-Zaklynska; she was given lavish receptions and lots of flowers and always drew thunderous applause. But still…

Somewhere in the mid-1960s Gerdan-Zaklynska’s health began to deteriorate perhaps due to excessive psychological and emotional exhaustion.

The absence of home comfort and elementary family warmth had an impact on her. It was more and more difficult for her to maintain a proper rhythm, combining the work of choreographer and director of her own school at the Ukrainian Music Institute in New York, conducting master classes, and developing new personal creations. In March 1965 she handed over to the US-based Archive-cum-Museum of the Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences 414 items of her personal archive, including, among other things, pictures, billboards, prospectuses, and press reviews. As Olenka’s memory weakened, her relatives in south-eastern France invited her to their place. She spent a lot of time here in the open air among luxurious nature, but she was lonely as an artiste. Unfortunately, nothing is known about this difficult period in her lifetime. But the very fact of sending to the journal Nashe zhyttia of the poem “The 1,000th Anniversary of the Baptism of Ukraine” with the epigraph “Still my thoughts are flying to you, my ruined and hapless Land!” (which was published) shows that even in the twilight of her life, in 1988, Olenka Gerdan did not abandon her Muses, particularly that of poetry. Unconfirmed reports say that she spent the last years of her life in a nunnery, where she taught the nuns to do rhythmic gymnastics. She went into Eternity also there, but the date of death and the place of burial still remain unknown.

This writer expresses sincere gratitude to Chrystyna Sochocka and Marta Trofymenko (Canada), Larysa Onyszkiewicz and Myroslawa Myrosznyczenko (USA), and Zoja Lisowska (Switzerland) for assistance in the search of materials about the life and oeuvre of Olenka Gerdan-Zaklynska.