Ivan Ilko, a giant of the Transcarpathian school of painting, Honored Painter of Ukraine, a pupil of the legendary Fedir Manailo, one of the dominant figures in mid-to-late-20th-century Transcarpathian painting, a talented and original artist, marked his 80th birthday with a retrospective exhibit, “My World, Verkhovyna,” at “Ilko’s Art Gallery” in Uzhhorod.

“BOKSHAI SAVED ME WITH ONE PHRASE”

Mr. Ilko, out of the thousands of canvases you have created in your rich artistic life, what do you like the most?

“There are two portraits I’ve been keeping with me for many years. I made them as far back as 1959. I painted them in Tiachiv and brought to an oblast exhibit. As they were not signed, my colleague Malchytsky gave them a collective title – ‘Verkhovynets’ (‘Highlander’). No sooner had I shown up at the opening than he said to me alarmingly: ‘Ivan, come here quickly, you’re being looked for.’ I went to the second floor and saw Yosyp Bokshai, Fedir Manailo, Anton Kashshai, Vasyl Svyda, and a man I didn’t know standing there. I had a necktie and a Komsomol [Young Communist League. – Ed.] badge on. Looking at me, the stranger cried out: ‘He is a Komsomol member to boot!’ and began to rant: ‘How dare you show Soviet Transcarpathia as a country of highlanders with bags?! How long are you going to depict antiquity? You should have shown a power saw, a radio, and what do you glorify? Is it a true Komsomol member?!’ I was embarrassed and began to tear the pictures off the wall. But the strings proved to be strong. I failed to tear off the work that enraged the boss so much, but the other four fell down. A moment of silence. Then he pounced on Svyda, the chief of our league.

“I was standing and didn’t know what to do. I knew that just one phone call would be enough not to allow me to write numbers on a truck body, let alone paint. How could I live on? At this moment, Bokshai, came up to me. He had just been awarded the title of People’s Painter and Academy Corresponding Member in Moscow and wielded unquestioned clout. The stranger shut up. ‘I see no problem here. It is our best work on display,’ Bokshai said. He saved me with this phrase. The stranger turned out to be secretary of Party’s oblast committee. That was the end of it, but almost everybody was looking askew at me. Since then, these two pictures have always been adorning my studio and been sort of my artistic amulets.”

Would you tell me about your art ways?

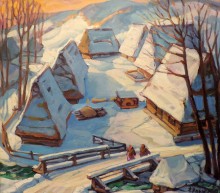

“In 1957, when I went to the Uzhhorod Art School, my teacher Fedir Manailo was in fact booted out of it. He was replaced by Anton Shepa. He brought in a new wave of the Lviv school of painting, the two schools began to merge, which was a positive development. I went with him to the mountains: at the foot of the Borzhava Ridge we ‘discovered’ artistically extraordinary places – the picturesque villages of Richka and Tiushka in Mizhhiria raion. These places often occur in my pictures. I first found myself in Richka in the winter of 1959. I saw snow-covered thatched houses and met with marvelous people.”

What makes Richka particularly fabulous?

“It is, first of all, the profound religiousness and openheartedness of its residents. Religiousness is the basis of everything. Secondly, the village is small and more or less self-sufficient. Everybody had a plot of land and 20-30 sheep and was busy making ‘gunias’ [local outfit. – Ed.] and doing subsistence farming. Then they ‘had their wings clipped’ when they were robbed of land. But our peasants are resourceful – they will always find a piece of ground. When the farmer is self-sufficient, he glorifies himself and says he is an owner. It is very important psychologically. People were very friendly to me here. I painted portraits of many local old-timers. I knew that this kind of people would vanish forever. It is a generation, our history.”

“FATHER WAS TOLD NOT TO GO BACK HOME, BUT HE WAS FULL OF PATRIOTISM”

The history that lives on in the reminiscences of your generation and in your pictures… And was your family not typical of Verkhovyna?

“Our family also lived a rural life. However, the river regularly washed off fertile littoral fields, only leaving sand behind. The Ilkos were rather well-off. Grandfather and great-grandfather were village headmen. I first saw father when I was 7. He had gone to France in search of a job, worked at coalmines for 16 years, earned and sent us handsome money. Mother built a house and a corral, and bought some land because Jews sold it on a mass scale in 1942-43. As long as I remember myself, I was responsible for something. For example, I looked after chickens and lambs. I was brought up to do some work.

“Father let us hear from him in 1945 – he was paymaster of the USSR Repatriation Committee in France, had a Communist Party membership card signed by Maurice Thorez and the certificate of a member of the National Front of France, and was eligible for a pension as member of the French Resistance movement. He was told in France not to go back home, for there was poverty and ruin there. But he was full of patriotism.

“Life was more or less good until 1948, when people began to be robbed of land. Then life worsened. When a collective farm director was being elected, father said about the candidate: ‘He only used to steal hens!’ Of course, they didn’t listen to him. Soon we had almost everything taken away. We didn’t even have a place to plant potatoes. They only left a cow. When they came to take away Bilia, our nanny goat, I grabbed her and began to shout: ‘I won’t give her to you!’ And those people left her. She literally rescued us later.

“Father was jobless for a long time. Then he was employed to build a bridge, for he was a jack of all trades. The pay was meager, but he was entitled to a ration of 25 kilos of corn flour. It was invaluable, for we could thus make mamaliga for a month. Dad brought a hair clipper from France, so he moonlighted by giving his fellow villagers a haircut. I also learned to give a haircut at 9. I could even do the faux hawk, while dad could not. Even bridegrooms would come to me.”

“A BRIEFCASE OF MONEY FOR PORTRAITS OF LEADERS”

Why did you choose to study the art of a painter?

“It was a big event in the village, when a movable film projector was brought over once a week or two. I helped a relative to write posters and placards in the club and drew wall newspapers at school. Then it became a vogue in villages to draw flowers over beds. I bought some wallpaper and painted roses far and wide. Women used to come even from the neighboring villagers to buy pictures. I liked it very much. Whew I was applying to the Uzhhorod Art School in 1952, I drew my roses at the entrance exam in composition.

“It was a hard time. I was 194 cm tall and always hungry. It was impossible to buy any food. Every day I went to stand in a breadline at 6 a.m. and sometimes waited until noon. There were barrels with sprats in the store: I would buy a kilo and bring it to the dormitory. The very sour bread and the very salty sprats were shared among all of us. The sensation of satiety lasted for… an hour or so. Soon I began to earn good money – Manailo, who was making watercolor sketches for the theater, invited me to draw from life.”

What did you do after finishing the art school?

“In 1957 I came to Mizhhiria to teach drawing. I taught draftsmanship to the future Shevchenko Laureate, poet Petro Skunts. Then I was authorized to give history lessons. I taught the material the way I deemed it necessary, spoke about the Renaissance… Deputy Principal Bardakov sat in on my third lesson and summoned me to a school board meeting, where he rode roughshod over me – the Renaissance, propaganda of religion… They allowed me to teach draftsmanship and manual labor only. I could no longer earn a comfortable living – I ran up a housing debt and had no money to buy food. I barely scraped up money to go back home.

“On the eve of Easter Day, mum gave me 10 rubles and told me to go to Tiachiv to buy some foodstuffs. In Tiachiv, I met Vasyl Kost, my fellow student from Bushtyn. He said: ‘Ivan, you are a godsend’ and took to his studio. There were 10 canvases there, which were to be finished by May Day. I took the paint, mixed colors, tied a paintbrush to the stick, and began to paint… Lenin. No sooner had I finished the beard and begun to do the necktie than I heard some noise behind my back. I turned around and saw the bosses looking at my work. Then the chief of them asked: ‘Do you have permission to paint portraits of leaders?’ I said that my exams had been conducted by a state commission, I got an excellent mark in the subject of ‘portrait,’ and I think this enables me to paint portraits. They agreed.

“Work was in full swing – I painted the portraits of Marx, Engels, and Lenin. A week later, father came from the village in search of me, for I hadn’t said I worked in Tiachiv. When it was time to be paid for work, I had to buy a briefcase because I couldn’t otherwise carry the money home to Dulovo. I bought everything we needed for Easter Day at home and put the briefcase with money on a bench. Mum and dad are coming up, and I’m laying out the money. Father looks at this suspiciously and says: ‘I’ve traveled around the world and know that you can’t possibly earn so much money in 10 days. Let’s go to Tiachiv, and I’ll find it out where you took this money.” We came to the studio, and father opened the briefcase in front of the guys. Vasyl says to him: ‘We know that Ivan earned more money, but he insisted that the money be divided into equal parts among us. But if you are against, we’ll return the difference to Ivan.’ Dad was flabbergasted to hear that.”

“A PRO MUST KNOW EVERYTHING AND DO WHEN IT IS NECESSARY”

How was your life going when you moved to Uzhhorod?

“I didn’t want to move. I built a two-storey building and a posh studio in Bedevlia. It is 60 km from Rakhiv, Ust-Chorna, Kolochava, and Mizhhiria – it is my element! By that time, I had already decorated the Tiachiv club, the Soviet Carpathians health center in Truskavets, and worked in Crimea for several years.

“Uzhhorod was the beginning of a never-ending hell. Colleagues did not welcome me. To start with, as one in charge of the decoration of Zakarpattia Hotel, I persuaded Yurii Ilnytskyi to purchase pictures by Transcarpathian, not foreign, artists to hang in hotel rooms. But it so happened that more pictures were bought from one artist and fewer from another. And I became an ‘enemy’ for many. Intrigues went so far that I was dismissed as chief artist at the regional Artistic Fund for… professional inefficiency. Can you fancy that: I was a member of the All-Ukrainian Artistic Board a mere 1.5 years ago, but turned out to be inefficient in Uzhhorod? It was hard for me to bear this. But I never ceased to paint my favorite nooks of the Carpathians.”

Today, “Ilko’s Gallery” is the best modern exhibition hall in Uzhhorod. How did you hit upon this idea?

“The idea belongs to my son Mykhailo. He took part in reconstructing Ukraine House, was the creative director of the Eurovision Song Contest in Kyiv and in Baku. And the idea of opening a gallery… At first we wanted to make it a place where Mykhailo and his family could stay whenever they visit Uzhhorod. Then this idea assumed the outlines of a gallery. We’ve been working for five years now. The gallery opened at the same time with my solo exhibit to mark my 75th birthday. Later we hosted high-profile exhibits of Pavlo Bedzir, Tiberii Silvashi, Vasyl Betsa, well-known Paris artist Victor Vasarely, Slovak artist Nikolaj Fedkovic, Munich’s Pavlo Kerestey, and Lviv’s Oleksa Novakivskyi. Concurrently, we actively organize concerts.”

To what extent does the artist depend on inspiration in his or her work?

“I am very skeptical of those who say: yesterday I had inspiration, and today I haven’t. I don’t believe in this! In my opinion, there are two things: amateurism and professionalism. A pro must know everything and do when it is necessary. There is always work that should be done – it doesn’t matter which one. Look at my works – they are made thanks to knowledge and professionalism.

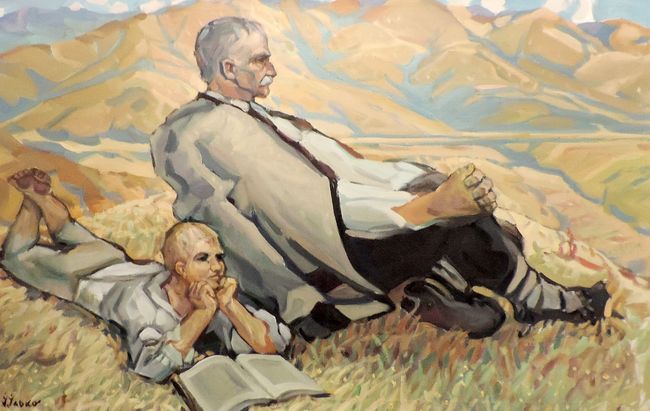

“My favorite theme is the Carpathians. And it does not matter whether it is a stone, a rivulet, or trees. I used to paint together with many well-known artists, such as Yablonska and Hlushchenko. They were just afraid of the Carpathians. If there is no contact, any painting is out of the question.

“It is no accident that I named my exhibit ‘My World, Verkhovyna.’ It is my theme. For nobody but me painted my uncle, father Shuhai. I do this not because I like it or not but because I am obliged to do this. The Carpathians were always a ‘pass-through yard’: Dacians, Celts, Goths… And only a small number of our people survived high in the mountains. A small group of our people went deep into the forests, cultivated fields, built houses, put up temples, and managed, throughout centuries, to preserve their mother tongue and original culture. My ancestors handed me down genetic memory, and God enabled me to paint and obliged me to thank for this gift, for belonging to this ethnos. And I have been doing this in all my lifetime.”