Both masters of choreography have left significant marks on the art of former-USSR, and Ukraine in particular. Critics named Konstantin Sergeev the lyric voice of ballet, and Vakhtang Chabukiani – the heroic one. We should remind The Day’s readers that Sergeev brought his variants of classical ballet heritage to Kyiv and Kharkiv, while Chabukiani, in addition to staging Laurencia in our country’s capital, was the head of the Ukrainian art and sports ensemble, Ballet on Ice, for a short period of time.

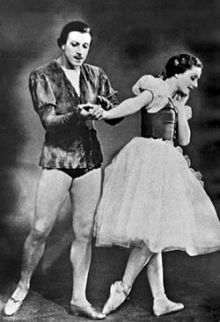

Sergeev and Chabukiani reached the famous stage of the Mariinsky Theater, which bore the name of Sergey Kirov at that time, in different ways. Sergeev a native Petersburger, and thanks to his artistic nature played lyrical and romantic roles. He was called the prince of Russian ballet of the 1930s and 1940s. His duet with Ulanova in the ballet Romeo and Juliet entered world choreographic history. The idyll of being in love was literally ruined by the second, though first according to rank, rival of Ulanova – the masterly and expansive Natalia Dudynskaya. She was the second partner of Sergeev and soon became his wife.

Perhaps it was Sergeev’s peer, the volatile Chabukiani, who was meant to be with passionate Dudynskaya, but life chose differently. Chabukiani was born in Tbilisi. He started to dance in the local theater named after Paliashvili. At the age of 16 he decided to continue his choreographic education in Leningrad. He soon became a dancer of heroic, extremely passionate characters with flaming temperament. While Sergeev, as a ballet master, usually limited himself to tactful alternations of classical works (for example, in 1959 he staged Giselle in Kyiv), Chabukiani became famous for his own ballets, set to the music of contemporary musicians, where he played the main male roles. Suffice it to mention the passionate and tragic ballet Otello or the heroic Laurencia. By the way, for playing the leading role there Dudynskaya temperament was actually needed — she danced at the premier in Kyiv in 1939 and, together with the young Rudolf Nuriev, in Saint Petersburg in the late 1950s.

The prominent dancers Chabukiani and Sergeev never met on stage during a performance, like the tenors Sergey Lemeshev and Ivan Kozlovsky in opera. Even in the ballet of Vasiliy Soloviev-Sedoy Taras Bulba they played the roles of Andrii and Ostap in different theaters: Chabukiani — in Leningrad, Sergeev — in Moscow. When their dancer’s career came to an end they almost met in Kharkiv. In 1978 Chabukiani’s ice dancing ensemble was there on tour. He staged Chopiniana, the famous ballet by Michel Fokine, which combines dancers’ extensive lines and Frederic Chopin’s melodies.

The old master was agreeable and relaxed in conversation. One could see that “steel spring,” which used to win bursts of applause after jumps and amazing turns of the dance virtuoso. Chabukiani told us that he accepted the offer to become a head of the Kyiv Ballet on Ice almost without hesitation, because he saw new possibilities and a challenging artistic experiment in it. His efforts turned to be productive. He spoke with excitement about the premier of the Olympic program in Kyiv, which was dedicated to the Olympic Games in 1980 in Moscow. He shared his plans about showing Faust on the ballet stage. It is sad that this dream of his never came true. He also told us that elaborate skating techniques (difficult elements which are closer to sport), do not guarantee that a performance will be an artistic success. However, no artist of the artistic and sport ensemble of ice dancing can reach full expressiveness without them.

“Artists have to master choreographic culture,” stressed Chabukiani. “One can’t just stage ice variants of performances. Every kind of art has its own laws. Therefore, one should create an absolutely original choreography for an ice ballet.”

By saying this Chabukiani expresses his disapproval of the Leningrad variant of Swans Lake on ice. At that time I didn’t know that Sergeev and Dudynksaya were the authors. Somewhat later those masters of choreography came to Kharkiv. The Leningrad ballet together with Sergeev staged Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty in Kharkiv. Three years later they staged Don Quixote by Ludwig Minkus. Both ballets were a great success and the dancers were at their best. Communication with bearers of high choreographic culture, brilliant pedagogues of dancing turned out to be very productive and could be felt for a long time in the performances of the Kharkiv dancers.

Sergeev loved to talk about his artistic career, about meeting great artists, particularly Sergey Prokofiev, whose variation of Zolushka (Cinderella) was probably the best version of the ballet ever staged. Besides, one could not resist the charm of his powerful and somewhat lordly personality. Sergeev’s rehearsals were especially expressive. The whole troop would come to watch them. By that time the great dancer and ballet master was already the head of Vaganova Leningrad Academic School, which celebrated its 240th anniversary in 1978.

Sergeev stressed that: “The notion of ‘dancing school’ is much wider than simple apprenticeship. Every artist of the old generation, just like myself, is proud that he belongs to his school and tries to pass the baton of artistic traditions forward.”

Kharkiv ballet, in its turn, can be proud that it became a part of these traditions. Besides, it turned out that Dudynksaya spent her childhood in Kharkiv on a street with the prosaic name Kontorska. The famous ballet dancer learned the basics of ballet art in her mother’s studio. Her mother was Natalia Dudynskaya-Tagliori. However, this is a completely different story best saved for Dudynskaya’s 100th anniversary, which will be marked in 2012.