One day in April 1906, a man a little over 30 years of age was found hanging by the neck at a private cottage not far from St. Petersburg. Some time later tsarist criminalists identified the body as that of Heorhiy Apollonovych Hapon.

Soviet history never pitied this well-known man. For a long time Soviet historians considered Hapon “a true defender of the tsarist regime,” “police provocateur,” and “out-and-out counterrevolutionary,” who dedicated his life to a struggle against the people’s revolution. However, an objective study of his brief life (he would have turned 35 at the time of his death) convinces one that those who regarded Hapon as a police provocateur and servant of the tsar, and continued to do so, have not understood anything about him.

HAPON’S UNIVERSITIES

Hapon, who was our fellow countryman of Ukrainian parentage, was born in 1871 in Biliaky, a village in Poltava gubernia. Later he testified that he came from a poor village family. However, certain facts in his memoirs indicate that Hapon actually grew up in a “strong” peasant family of average means. Heorhiy made no secret of his social views and suffered for this at least on two occasions: when he was a student at the theological seminary in Poltava, he was deprived of his state stipend and received a second-class diploma instead of a first-class one, clearly an injustice, considering Hapon’s excellent abilities and knowledge.

His diploma, in turn, considerably complicated Hapon’s enrolment in any institute of higher education in the Russian empire. Hapon first arrived in St. Petersburg in 1902 and, as was to be expected, he did not restrict himself to studying various theological disciplines. He plunged headlong into the lives of those social strata whose representatives were so skillfully portrayed in Maxim Gorky’s famous play The Lower Depths. In this he was helped by the posts he occupied while studying at the academy. Hapon worked as a priest in the Blue Cross asylum and in the Olginsky Home for the Poor.

Hapon was spiritually close to the “people from the lower depths” — unemployed people and beggars — and he frequently pondered the weighty question: how could he improve their hard lives. It should be noted, however, that the man from Poltava did not contemplate the need to make violent changes in society; he believed that the lives of the poor could be substantially improved within the existing political system. His ideas resulted in a project envisaging the creation of special labor colonies in the cities and the countryside, where poor people would have an opportunity to do socially useful work and receive adequate remuneration

At the same time, Hapon’s irrepressible ideas went further, lending greater scope to his social projects. Eventually his labor colony project was replaced by a new idea, the creation of an all-Russia workers’ organization that would use nonviolent methods to force the tsarist government and the capitalists to seriously consider the interests of the proletarians and substantially improve their lives. At the same time the student encountered all sorts of troubles that dampened the impassioned flight of his thoughts. His projects to organize labor colonies were shelved.

To make matters worse, Hapon was soon relieved of his posts at the asylum and the home for the poor, and expelled from St. Petersburg Theological Academy. The young man had every reason to feel desperate, but suddenly nearly all his problems were quickly and almost effortlessly solved. Hapon was reinstated in the academy and both clerical posts. Some time later he found himself stepping into the large and spacious office whose occupant was a solidly built 40-year-old man with a warm expression and polite manners. His name was Sergei Vasilyevich Zubatov, and he was a colonel in command of the Special Section of the tsarist Department of Police.

UNTYPICAL AGENT

Zubatov may be justly considered a true innovator in the question of protecting the tsarist autocracy. Indeed, he was the first to introduce a cardinal change in the methods of combating the antigovernment movement. Zubatov believed that repressive measures were effective in the struggle against the comparatively few Decembrists and members of Narodna Volya. Now, such measures could prove inadequate, considering the very likely possibility of a struggle against the revolutionary workers, who numbered in the millions at the start of the 20th century.

Like a good physician who prescribes prophylactic treatment in the face of a serious disease, the colonel in the Special Corps of Gendarmes set himself and his subordinates the task of forestalling various antigovernmental movements by creating workers’ societies in which the police department’s experienced propagandists would hammer into proletarian heads the idea of substantially improving their financial position without a revolutionary struggle.

Naturally, the priest from Poltava, who was obsessed with ideas about nonrevolutionary workers’ organizations, was quickly noticed by the omnipotent Department of Police. Zubatov decided to support the man he needed (this is when most of Hapon’s problems vanished) and proposed close cooperation. His talks with Hapon inspired the colonel. True, in his young guest Zubatov quickly discerned an exponent of the Western constitutional order, but he was certain that Hapon would do exactly as he was told. However, in viewing the situation this way, Zubatov obviously underestimated the young priest, who had no intentions of becoming another pawn on Zubatov’s chessboard.

In the end, the head of the Special Section invited Hapon to head a workers’ society created by Zubatov in St. Petersburg. Hapon, however, was disappointed when he familiarized himself with the colonel’s organization. Instead of a truly independent and influential workers’ society, the priest saw a rather gray and ambiguous structure in which the workers could not take a single step away from the Russian gendarmerie’s watchful eye. Hapon told himself that under these circumstances, any kind of cooperation with Colonel Zubatov would be not only immoral but also criminal. However, considering that no civic organization could arise without the knowledge and consent of the Department of Police, the priest agreed to his proposal, on condition that he would create an entirely new workers’ society in the capital.

Zubatov agreed to Hapon’s condition and a new organization appeared in St. Petersburg in February 1904: it became known as the Assembly of Russian Factory and Plant Workers of St. Petersburg. It should be emphasized that in founding the assembly, Hapon scored two important victories. First, its action program was not subject to the police department’s approval, and second, the police had no right to arrest any of its members. Thus, Hapon managed to create an organization whose membership eventually reached 20,000 and which enjoyed a degree of independence unprecedented in autocratic Russia.

Needless to say, Hapon used that independence in strict accordance with his own objectives. Lectures occupied an important place in the assembly’s activities, but the visiting lecturers mostly taught the workers not reconciliation with the capitalists (Colonel Zubatov’s desire) but methods of struggle against capitalist exploitation. If Lenin had attended one of those lectures, he would have been quite satisfied.

SPROUTS OF REVOLUTION

Did the tsarist functionaries suspect what kind of organization Hapon and his like-minded workers had created? It is perfectly safe to assume that its true nature was realized only by the tsarist Prime Minister Sergei Witte, who stressed time and again that Hapon’s organization was a purely revolutionary one that sooner or later would attack the autocratic regime. Other tsarist administrators trusted Hapon unquestioningly, naively believing that he had succeeded in creating an “updated version” of Zubatov’s movement. Hapon and his closest associates took advantage of this and were preparing their organization for the time when decisive action would be taken. That time came on January 9, 1905.

The paradoxical fact is that the road to what we all know as Bloody Sunday was paved by the administration of Russia’s most famous Putilov Factory. Like Witte, the Putilov administrators understood the assembly’s revolutionary nature and its hostile attitude to them and their rich employers. Wanting to teach the workers a lesson that would forever discourage them from joining that organization, the factory managers summarily dismissed four workers in February 1904. Their dismissal was accompanied by sarcastic remarks, like “Why don’t you go to your assembly? They will help you!”

Accepting the challenge, Hapon spent hours with the factory administration, demanding immediate reinstatement for the unlawfully dismissed workers. The administration held its ground and the Putilov workers went on strike. Soon they were joined by most of the other industrial enterprises in the capital. Passions quickly reached the point that the workers were prepared to champion not only economic demands but political ones.

At the same time the most radical members of the assembly conceived the idea of confronting Tsar Nicholas with a petition containing demands to liquidate the vestiges of feudalism in the countryside, provide the population of the Russian empire with extensive democratic freedoms, and immediately convene a Russian parliament, the State Duma. This important revolutionary act was to set the stage for the substantial sociopolitical transformation of Russian society (if the tsar agreed).

Hapon fully approved the idea of petitioning Nicholas II. Some believe that he was its author, but it was probably a joint endeavor, as Hapon invited several social democrats to take part in drawing it up. Arrangements were prepared for a march to the tsar. The priest forbade the workers to carry red flags and weapons, so as not to give the government cause to use force.

The tsarist government was not sitting on its hands, either. The initiative of Hapon and his organization was no secret to the authorities. Shortly before January 9, Hapon was summoned by Ivor Fullon, Governor General of St. Petersburg, who asked with obvious anxiety whether it was true that the head of the St. Petersburg Assembly was going to lead the workers to a meeting with the tsar. Without batting an eyelash, Hapon assured the governor-general that it would never happen.

Hapon would write later about how well he had deceived “old Fullon,” adding a phrase that could serve as an aphorism: “You can’t make a revolution without telling lies!” But the governor-general was not as simpleminded as Hapon thought, and mustered a large number of troops to St. Petersburg in advance.

It should be added that prior to the tragic events in January the Department of Police also took a sober look at the situation. They finally realized that Hapon had never actually been Zubatov’s man. On the contrary, by exploiting the support of the tsarist special services, Gaposha (as some police officers referred to him) had imperceptibly led Russia toward revolutionary transformations. On January 8, 1905, the Department’s Special Section issued an arrest warrant for Reverend Hapon. They failed to apprehend him, not because the head of the Assembly took special pains to hide from the authorities but because he was always accompanied by a large crowd that made an arrest physically impossible.

“WE NO LONGER HAVE A TSAR!”

What happened later has been described by many historians, and our readers are well aware of this. The tsarist troops opened fire on the peaceful marchers, an action that left Hapon in a state of shock. He then addressed the workers with a phrase that was repeated in many history books: “We no longer have a tsar!” That same day, around midnight, Hapon wrote a message to the Russian workers, urging them to rise up in arms against “this beast of a tsar.” Thus, the leader of the capital’s proletarians, affected by the atrocious events of January 9, reached the conclusion that it was necessary to wage an armed struggle against the tsarist regime, an idea that until recently he had utterly rejected.

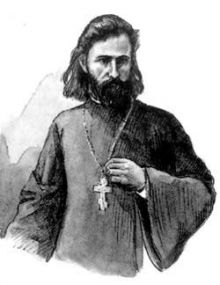

Under the circumstances, his further stay in Russia was fraught with considerable danger, so Hapon cut off his long black hair, donned a pair of glasses, and arrived at the Tsarskoye Selo railway station one evening to board a train for Finland. As it transpired, they were waiting for him there; the revolutionary priest quickly spotted several officers of the gendarmerie. At that moment Hapon almost physically felt that the success of his emigration largely depended on his self-control. Boldly approaching one of the officers, Hapon asked for a cigarette. The officer did not recognize him and gave him a smoke, whereupon the man very much on the police wanted list calmly boarded the train. In a short while Hapon arrived in Finland from where he and a group of smugglers crossed the state border of the Russian empire.

At the time, the name of the leader of the St. Petersburg proletarians made headlines across the world. A number of noted emigre revolutionary leaders (among them Vladimir Lenin and Georgi Plekhanov) considered it an honor to meet and talk with the man whose action had triggered the first Russian revolution. It is also true, however, that they soon realized that the “godfather” of January 9 was markedly undereducated in political terms. He was primarily attracted by active revolutionary work and here Hapon was certainly at his best. He wrote several messages calling for an armed struggle against the autocratic regime, arranged to send the ship Crafton to the revolutionaries in Russia with a large supply of weapons, and made every effort to collect money for the sailors of the Potemkin, who had ended up abroad.

As time passed, however, the prospects of a revolution to overthrow the tsarist regime were becoming increasingly problematic. Hapon’s mood worsened and soon not a trace was left of his former energy. Then Hapon’s vigor received a powerful impetus after Tsar Nicholas published a manifesto granting the people extensive democratic freedoms. His eyes shining, Hapon told his friends that he was returning to Russia immediately.

The reason for this sharp change in Hapon’s mood is easy to establish. In the tsarist manifesto he saw what was most important to him: an opportunity to legally found and manage an all-Russia workers’ organization; his long-cherished dream seemed to be coming true.

In order to implement this dream Hapon worked out a flexible tactic. On the one hand, he was outwardly prepared to cooperate with the tsarist government, which is understandable; it depended on him whether the activities of his organization would be actually renewed. On the other hand, he decided to maintain contacts with a large group of socialist revolutionaries led by Pinkhus Rutenberg and even help them with their struggle, which was again understandable. Hapon knew only too well that the tsarist government’s need for him and his assembly would always be proportional to the pressure of armed revolutionaries on tsarism. The stronger the pressure, the more valuable Hapon would be in the government’s eyes.

A MISUNDERSTANDING THAT COST A LIFE

Some time after the amnesty Hapon began meeting with two high-ranking police officers, General Rachkovsky and Colonel Gerasimov. They made it perfectly clear that the assembly would be allowed to operate only after Hapon resumed his activity as a police informant in the revolutionary movement. The Department of Police was particularly interested in the socialist revolutionaries’ plans for acts of terrorism against top- level tsarist administrators. To their profound disappointment Hapon told them almost nothing. Neither Rachkovsky nor Gerasimov knew that Hapon was regularly reporting their secret conversations to Rutenberg. The potential tsarist informant told his comrades on more than occasion that he wanted to be a revolutionary agent planted in the police, which function was at one time carried out by certain members of Narodna Volya.

During his many conversations with Rutenberg, Hapon repeatedly proposed a number of terrorist acts, like blowing up the Department of Police, assassinating Rachkovsky, Interior Minister Durov, even Nicholas II. On one occasion Hapon suggested that he would inform Rachkovsky about several socialist revolutionary militants’ operations scheduled for the nearest future, so that he could be paid an enormous sum (some 100,000 rubles). The money would help enlarge the scope of the revolutionary struggle dramatically.

Rutenberg treated Hapon’s suggestion with a great deal of suspicion; he understood it only as an offer to become a paid police agent. Unfortunately, the leading socialist revolutionary paid no attention to details that clearly indicated that by carrying out the scheme, the revolutionaries would gain much more than the tsarist police. Very quickly he arrived at the simple, and erroneous, conclusion that Hapon had become a paid police agent.

In late March 1906, Rutenberg invited Hapon to a private cottage in Ozerki, where several armed workers were also scheduled to arrive. When he arrived at the dacha, Hapon immediately informed Rutenberg that the police department’s command was inviting the socialist revolutionary leader to deliver up his party’s so-called combat group and that he would be paid 25,000 rubles. Rutenberg asked if it would be possible, after returning the money, to warn the group about their impending arrest. Hapon replied that it was.

If Rutenberg had only paid more attention to Hapon’s words, he would have understood that the “agent provocateur” was offering a totally realistic plan that was unquestionably advantageous to the underground socialist revolutionaries. As it was, Rutenberg conducted that conversation for the sole benefit of the armed workers in the next room, who could hear every word and become convinced that Hapon had turned into a police agent.

Several minutes later they burst into the room and surrounded Hapon, who was completely taken by surprise. Hapon instantly understood what was happening and asked his executioners to hear him out. But they were determined to carry out a lynching and denied him a last word. A few minutes later Hapon was hanged from a coat rack.

Neither then nor later did Rutenberg or his comrades in arms ever doubt that they had executed Hapon with good reason, as an enemy and informant of the Department of Police. But was the “godfather” of January 9 either one? Of course, in order to become a true agent provocateur, Hapon would have had to carry out a number of characteristic actions, like regularly informing the tsarist police about revolutionary organizations, cautioning the police against their revolutionary plans, betraying revolutionaries to the tsarist special services, recruiting informers in their midst, and so on, without causing any harm to Nicholas II’s regime.

Yet it is an established fact that he did nothing of the kind. In fact, it is unlikely that Hapon would have been able to combine collaboration with the Department of Police with his concrete endeavors for the good of the revolution. Therefore, I am absolutely convinced that the old, threadbare myth that Hapon was a police provocateur must be laid to rest.