On the Ukrainian artist who was taught by famous Polish artists at the Krakow Academy of Arts, took part in the restoration of Wawel, one of Poland’s main national symbols, and was killed by Polish fighting squads when he only had a painting set about him.

This story is for the edification of some complacent and shortsighted contemporary Polish political “lawmakers” who brutally intrude into the cultural memory of the Ukrainian and Polish peoples.

The early life story of Oleksandr Kharkiv did not show even the slightest hint of a likely artistic vector of professional development. He was born on March 1, 1897, in Kremenchuk, Poltava region. When he finished the local secondary school, his parents urged him to apply to the Electro-Technical Institute in Petrograd, one the Russian Empire’s most prestigious educational institutions at the time. As World War One broke out, he was mobilized to the tsarist army. In 1918 he joined the army of the Ukrainian National Republic, where he rose to the rank of lieutenant. Kharkiv turned over a new leaf in 1920, radically changing his professional interests.

Kharkiv begins to show certain creative inclinations in the context of events in that period of change, when dozens of thousands of Ukrainians had to resign themselves to the loss of hopes for an early comeback home. By accounts, these inclinations were obvious when he was still at the front. Further proof of this is the fact that, in first months of staying in the camp for interned UNR army servicemen in the Polish town of Lancut, the Poltava-born man took an active part in the events to honor the memory of the killed participants in the Ukrainian national liberation movement. His name was first associated with the projects of a monument to fighters for the freedom of Ukraine in February 1921. As a chronicler notes, “two projects were offered by the Station chief and quartermaster. Their concept was modified and implemented by the Station decorator Oleksa Kharkiv, a UNR army lieutenant.”

The Lancut camp had one of the best cultural and educational infrastructures. It comprised a people’s university, a lot of leagues and artistic institutions. Kharkiv and his friend Oleksandr Stovbunenko, a beginning sculptor born in Bila Tserkva, frequented an “art studio with a sculpture section” set up back in 1920. The studio was run by Vasyl Kryzhanivsky, an alumnus of the Kyiv Painting School, a highly-gifted painter and graphic artist, and, later, a trusted friend of Kharkiv. In July-August 1921, the camp, with all of its facilities, was moved to Strzalkow, and some of the students and their supervisor left for Krakow to apply to the Academy of Arts. By the results of a competitive exam, Kryzhanivsky and his pupil Kharkiv were enrolled in the first year of studies at the academic class of Professor of Painting Stanislaw Debicki. “The 1921-22 academic year was very hard to us, for we lacked a lot of things,” Kharkiv’s fellow student Vasyl Perebyinis wrote. “We were still wearing military uniforms, some of us didn’t know the language and made payment for the first semester only, and remained penniless.”

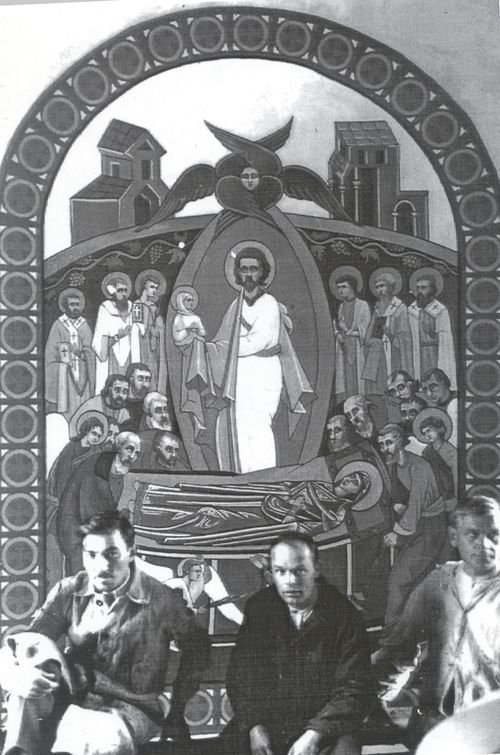

OLEKSA (CENTER) WITH COLLEAGUES AGAINST THE BACKDROP OF THE KLYMIVKA CHURCH ICON

Kharkiv’s first academic mentor Stanislaw Debicki, a prominent and experienced portrait painter, decorator, illustrator, and easel graphic artist, a former member of the Vienna Secession, was finishing his artistic career. After his death in 1924, Kharkiv attended the classes of the famous Jozef Mehoffer, Felicjan Kowarski who specialized in decorative painting, and Jan Wojnarski, a noted master of graphics – one semester with each. The diverse art concepts these artists adhered to made an impact, one way or another, on the young Ukrainian artist’s manner of painting.

Once he became an Academy student, Oleksandr, already called Oleksa by that time, began to take an active part in extracurricular life. Documentary sources refer to him as member of the well-known literary and artistic society “Rainbow” founded in the Kalisz camp on the initiative of Yevhen Malaniuk, Ivan Zubenko, Fedir Krushynsky, and other leading representatives of the young Ukrainian intellectuals in emigration. In the fall of 1922, the camp hosted a big art exhibit of “Rainbow” members, which was relocated to Kalisz on November 28. In a review of the exhibit, Malaniuk wrote that “Mr. Kharkiv’s watercolors, the essence of the studio, have some value for their author only,” which is right, taking into account that the young artist was taking the first steps in art. In the same year, he took part in the first exhibit of the Lviv-based Society for Ukrainian Art Figures (GDUM) and donated one of his watercolors “for a lottery in favor of the disabled UNR army servicemen who stay in camps.” Besides, in 1922-23 he, together with his Academy friends Leonid Perfetsky and Oleksandr Karpenko, took part in doing polychromic work in the church of Zubets, near Buchach. At the same time, the portfolio of his easel paintings was being filled with high-quality pictures. None of the witnesses of Kharkiv’s artistic growth had any doubts that art was his true vocation.

“THE RIVER STRYI NEAR DULIBY,” 1937, OIL

The art pieces by which Oleksa Kharkiv manifested his artistic ambitions – watercolors, oil studies and pictures, drawings, and etchings – are rather different by the level of artistry, esthetics, and mastery. The now available information does not give an unequivocal answer about the correlation of various fields of art, in which Kharkiv realized himself in 1921-26. Yet there was also an ever-obvious regularity in the fragmentary nature of Kharkiv’s conceptual steps – painting was becoming an important part of his life, which showed unshakable loyalty to the chosen professional path.

A 1925 etching named “I Have Great Pity” is undoubtedly one of the turning points in Kharkiv’s oeuvre. It is sort of a quintessence of a young Ukrainian’s turmoil on the crossroads of life, a hidden reflection of nostalgia for the homeland he had to leave in the critical years of a wartime storm. On the other hand, this work was a synthesis of his discoveries of modern ideas of art, so well presented in Krakow, an important cultural and artistic center of Central-Eastern Europe. As soon as the next year he sent one more philosophy-themed etching, “A Scene from the Apocalypse,” to the GDUM exhibit, which proved that he had done intensive intellectual work in the years of Academy studentship. At the same time, Kharkiv practices in the genre of landscape. The surviving “View of Krakow” (1927) allows drawing a positive conclusion about the author’s professionalism. The work seems to have been done in a burst of inspiration, for the artist managed to find a poetic image of the city.

Unfortunately, there is no other Krakow-period picture or study left, which would let us find the pattern of the development of the author’s gift for painting. Maybe, Kharkiv had too little time for easel painting because the then administration of the Krakow Academy of Arts (especially when Alfred Szyszko-Bohusz was its rector) attached the greatest importance to architecture, renovation, conservation, and restoration of outstanding historical monuments. When Kharkiv was still a senior student, he was invited to do restoration work in Wawel, which was in itself a manifestation of confidence in the Ukrainian student on the part of professors. At the time, the young artist made a group of medallions with the images of evangelists in the technique of fresco and restored the polychromy of castle rooms as well as frescoes in the Jagiellonian Library. With this experience, the young Ukrainian could look into the future more confidently. Besides, according to Perebyinis, he gets married in Krakow at approximately the same time, which somewhat eases his psychological condition.

In 1926 Kharkiv decorates the Ukrainian Church of the Holy Virgin’s Assumption in the Lemko village of Klymivka, Gorlice County. He wrote to a friend on this occasion: “After working in Wawel a year for other people, I would like now to work for our people. Although it is hard to do so from the material angle, it is easy from the spiritual angle, for you have a pleasant feeling towards your people and you torment yourself over them.”

“I HAVE GREAT PITY,” 1925, ETCHING

The religious sphere increased Kharkiv’s efficiency on the whole. After moving with his wife to Jaworow (Yavoriv) in 1928, he assumes the office of teacher of painting and drawing at the Basilian Sisters Seminary and the Ukrainian Makovei Gymnasium. The six years of staying in the Jaworow district were extremely fruitful. In that period he created a series of watercolor and oil landscapes, genre compositions, and some purely ethnographic scenes. Most of the survived works are of a study nature, but they are executed in a lively painting key.

Incidentally, the job of a teacher aroused Kharkiv’s interest in the environment because he was not only an artist, but also a connoisseur of traditional culture. He participated in the organization of the “Yavorivshchyna” historical and ethnographic museum. The central easel-painting picture he created in this period was “Yavorivka” (1933, oil) – a down-to-knee image of a beautiful young woman in a folk costume. This work drew a societal response and was even displayed at the Ukrainian pavilion of the Chicago World’s Fair (1933-34).

“YAVORIVKA,” 1933, OIL

Museum work captivated Kharkiv. From then on, his working day was divided into periods of teaching painting and drawing at school, nonprofit work (also in the museum), and professional activity. What took most of his individual time and effort was his practice as monumental artist and restorer.

The final period of Kharkiv’s life and work was associated with the city of Stryi, where he held a professorship at a girls’ high school.

The late 1930s saw the peak of Kharkiv’s intellectual development. He became a major public and cultural personality, and the level of his artistic pursuits was on the rise. But all his further creative prospects were ruined in a particularly cruel way. The entire Stryi district talked about the tragedy that occurred on the outskirts of Stryi (in Vilshyna Park) on September 14, 1939. The artist’s friends, who were very far from this place, also recalled it. On that fatal day, a Polish terrorist unit (admittedly, the Border Security Corps – Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza, KOP, a military formation to defend the eastern borders of the Polish Republic) cynically claimed the life of two Ukrainians – Zenon Okhrymovych, 21, a student at the Krakow Academy of Arts, and Oleksa Kharkiv, a 1926 alumnus of the same institution. The militants were very indifferent to the profession of their victims – they were guided by the inhuman instinct. Poland’s chauvinistic radicals were going to use the sadistically mutilated bodies to intimidate the entire Ukrainian population of historical Galicia. A pupil of outstanding Polish pedagogues, a coauthor of restoration works in Wawel, a humanist and esthete, Oleksa Kharkiv was eliminated by a paramilitary force of the Polish authorities in a particularly cruel way, without the slightest legal or moral-ethic foundations.

Roman Yatsiv is Pro-Rector of the Lviv National Academy of Arts