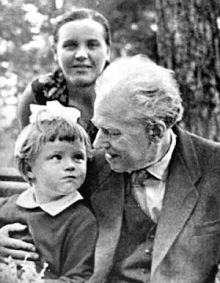

Recently, there was the 120th birth anniversary of Pavlo Tychyna — outstanding poet, academic, musician, and artist, and Soviet-era official — his great-granddaughter Tetiana SOSNOVSKA, now director of the Tychyna Literary and Memorial Apartment-Museum in Kyiv, spoke about this unconventional man.

Before the interview Sosnovska showed a sketch of the five-hryvnia commemorative silver coin that was recently issued by the National Bank of Ukraine. It displays an unusual image of young Tychyna created by the artist Volodymyr Atamanchuk. Before doing this he absorbed the poet’s legacy, visited the museum, read lots of his poems, and chose the words to engrave on the coin. Sosnovska believes the image is well turned. “We know Tychyna very well as a poet and a scholar. A part of this drawing shows Tychyna as an artist, but, unfortunately, you will find nowhere the musical facet of Tychyna’s talent. Maybe, we will show Tychyna the musician by the 125th anniversary of his birth,” she says.

Pavlo Tychyna was born at the village of Pisky, Chernihiv gubernia, on January 23, 1891 (the traditional date of January 27 is The Day of baptism, according to a record in the church book found among the Commercial Institute documents in the Kyiv City Archives). He was the seventh child of the village deacon Hryhorii. That his father was a deacon means that Pavlo received not only a serious religious but also (and above all), a musical education. For Hryhorii Tychyna, mostly engaged in religious and public affairs, was also a music enthusiast. Mother and all the children could sing very well. Pavlo was a born musician (he had perfect pitch) and painter. In 1912 Tychyna began to contribute to the journals Literaturno-naukovy visnyk, Ridny krai, Ukrainska khata, Osnova, et al. In 1913 to 1914 he published the short stories Babylonian Captivity and Divinity. Various critics tried to ascribe Tychyna’s works to a certain literary school, but the poet did not consider himself adhering to any of them. Yet he agreed that his poetry was influenced by such schools as symbolism, impressionism, and even futurism and imagism.

Totalitarian-era critics did their best to water down Tychyna’s oeuvre in order to hush up or distort his masterpieces, making a caricature of some of the poet’s really weak lines before schoolchildren’s naive eyes.

COLOR MUSIC

“Few know that Pavlo Tychyna was an unsurpassed music conductor,” Tetiana Sosnovska says. “When he was a Chernihiv Theological Seminary student, he conducted composite choirs at the local People’s House (now a philharmonic). At the seminary, Tychyna played the flute, the clarinet, and the oboe in the orchestra. He learned by himself to play the piano and the bandura. He was well-versed in music. His composer friends would come to his house to find the last chord to his own poems. Tychyna saw color in every sound. He used to say: ‘This music is gray-violet’ or ‘this music is of a fresh-green color.’ It was therefore not accidental that he accompanied Kyrylo Stetsenko’s choir in its tours of Right-Bank Ukraine, organized a young workers’ choir, and had a piano at home. Whenever elderly Kyivites came to our museum, they recalled hearing splendid music from the windows of the building near which they, as children, played. They thought a composer or a musician lived in the building. But Tychyna was the only tenant who had a piano. There were no musical instruments in the other apartments.”

The museum displays over 10 pictures by Tychyna, which his widow Lidia provided after his death. Tychyna was taught painting at a Chernihiv high school by Mykhailo Zhuk, who had graduated from the Krakow Academy of Arts with two silver medals. He groomed Pavlo for entering the Petersburg Academy of Arts. But the boy’s father died prematurely, and his mother, who had to care for nine children, could not raise enough money for the journey. Art researchers now say that Tychyna had a flawless sense of space and harmony. If only he had reached Petersburg, he would not have needed a return ticket.

EDUCATION COMMISSAR OF SOVIET UKRAINE

“Knowing about Pavlo Tychyna from family accounts, I cannot fancy him to be a bureaucrat. Perhaps he had good aides. Tychyna was appointed People’s Commissar of Education of the Ukrainian SSR in 1943, but he arrived in Kyiv only in 1944, when the city had been liberated from the Nazis. Tychyna held this office until 1948. Those were the hardest times for the country, when ruined schools were to be rebuilt and supplied with teaching staff, heating, copybooks, and manuals. At the time, the Ministry for Education was also in charge of museums. That higher education remained Ukrainian and pupils were taught on the basis of Ukrainian textbooks was entirely his merit. To be able to influence the schools policy, Tychyna, over 50 at the time, applied for Communist Party membership. He was admitted immediately, without having to be a candidate member first. Tychyna cared very much about teachers. He liked to mingle not so much with school principals as with rank-and-file teachers. He looked into the teaching process, asked a lot about problems, curricula, etc. Teachers could speak frankly with him. Tychyna tried to support them in some way. Teachers did not even know that what he often took from the drawer was his own money because he said it was a prize from the Ministry of Education. Educators were happy, not knowing that the ministry lacked money even for the rebuilding of schools. His fellow villagers in Pisky are now complaining that Tychyna had a one-storey school built in his native village that was burnt down during the war. They say he should have built a two-storey one, since he was a minister…”

TYCHYNA KNEW 20 LANGUAGES!

“He voluntarily resigned as Speaker of the Ukrainian SSR’s Supreme Soviet, the office he held from 1953 to 1958. He had read a draft law on closer ties between school and society, which envisaged a gradual cancellation of Ukrainian language classes for the children of military servicemen at the wish of the latter. Tychyna viewed this law as an attempt to Russify education, which he could not possibly agree to. At the time, all things were approved unanimously. Tychyna said the law was too ‘raw’ and needed to be improved. Then he was told on the phone that it was time to resign from the office ‘due to poor health.’ As the Supreme Soviet began its next session, a letter of resignation was read and approved unanimously. The deputies elected a new speaker and immediately passed the law on closer ties between school and society. Tychyna lived on for almost 10 years after that. So health was not the issue.

“It is not widely known that Tychyna was also a good translator. We tell schoolchildren that Tychyna did not have a higher education. Fate decreed that Tychyna did not graduate from the commercial institute that had been moved to Saratov in 1914. As a matter of principle, Tychyna cooperated with Ukrainian-language public houses only. They paid far less than the Russian-language ones did. This money was not enough for him to travel and take exams, so he had to drop out.

“We tell museum visitors that if a person is industrious, broad horizons will open up to them. Tychyna wrote not only poems. He wrote so many scholarly articles that he was very soon granted the title of academic. Only after this did he defend a doctoral dissertation, skipping the degree of Candidate of Sciences.

“Tychyna learned foreign languages on his own. At first he knew only three — English, German, and Latin. He learned the rest by himself. When he had already learned grammar and vocabulary, he would recruit a teacher who helped him acquire speaking skills. We can now say that Tychyna had an excellent command of almost 20 languages! Besides, he translated into Ukrainian from as many as 40 languages. He knew foreign languages so well that he could come to, say, Paris or Sofia and speak fluently to those who met him. His close acquaintances noted his noble conduct. He always shunned noisy assemblies. He never had a bottle in front of him. The events that Tychyna organized were always held in a refined, noble, spiritual, and well-mannered atmosphere. That is way he was called a refined intellectual.”

FROM SECURITY SERVICE ARCHIVES

“When the Security Service of Ukraine opened its archives, our museum and a Chernihiv researcher asked to be allowed to read the files on Tychyna’s brothers. One brother was arrested in 1923 for organizing and blessing the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church. Another brother, who worked for a Nizhyn newspaper in 1937-38, was arrested for counterrevolutionary activities. In this period Tychyna handed in his resignation as director of the Institute of Literature, an office he held in the 1930s, because he was unable to write poetry. Indeed, he wrote very little in that time. He felt ill at ease in both Kyiv and Kharkiv for fear of being arrested any day.”

A MUSEUM IN PISKY

“I am worried about the current situation at Tychyna’s home village and his ancestral house. The poet died on September 16, 1967. He last visited the village 18 months earlier. He did not come there very often, for the ashes of his brothers and sister had been scattered over Ukraine after his mother’s death. The poet lived in Kharkiv for 13 years and then headed the Institute of Literature. One of his brothers was arrested, and Tychyna later took him to his home and tried for a long time to draw him out of a depression. Then came the war, and he worked for four years as People’s Commissar of Education. Yet he never severed the spiritual link with the village. Tychyna subscribed to newspapers and magazines for the village school, library and acquaintances. He personally checked whether the subscribers received their mail.

“When the village had burnt down, the brothers besought Tychyna not to go there. Almost 800 people died there. In 1943 fellow villagers said in a letter that during the war the Nazis had locked all the villagers in a church and torched it, and that his niece Olia and her children burnt down there. In reality, she was killed on her own house’s threshold, but, in an attempt to move the poet to pity and shape a certain attitude to the events of that era, the Party activists decided to lie to Tychyna. After the war Tychyna got to know that Olia and her daughters lay buried in their own courtyard, but legends has already pervaded all newspapers and textbooks. Thus the ideological thought was formed.

“Pavlo’s elder brother Ivan decided to come back to Pisky after the war. He saw the modest grave of Olia and her children in the household courtyard — they were later reburied next to graves of mother and father. Ivan organized a school choir which the villagers still remember. And in 1967 he received a suggestion that a Pavlo Tychyna museum be built in the family courtyard. The museum began to be built next to the brother’s house. Ivan died two years later. Meanwhile, a plaque appeared on the museum wall, saying that it is being built on the occasion of… the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. When the museum was unveiled in 1972, it was named Museum of the History of the Village Pisky, in which only one tiny room was dedicated to the poet. Lidia, who would donate funds for the construction but was a modest woman, could do nothing against the very powerful Communist Party nomenklatura. This lasted for a long time. But then Anatolii Pohribny, who had begun his career as history teacher at the Pisky school, said that there must be a Tychyna museum in the village. Following his letter, a committee was formed, 127,000 Soviet rubles were allocated, the house patio was cleaned up, a 10km road was laid, the house was renovated according to the relatives’ reminiscences, and a monument was erected. But still it was a museum of the village’s history. The guides only show visitors the house of Tychyna, while the museum’s name remains still the same. Only when independence came and the tourist business began to burgeon, the highway saw an advert board reading ‘Tychyna Museum.’ But it is only on the highway.”

THE POET’S KYIV APARTMENT

“The Tychyna Museum in Kyiv has been open to visitors for 31 years now, the vast majority of them being school and university students. Yet family visits have also been on the rise lately, especially on Saturdays and Sundays. Eight years ago we introduced free admission on Sundays. These efforts were crowned with success. Young people and their friends come over. It is gratifying that the museum has become a test of sorts for young families. It is good that, to gage their spiritual level, young people choose our museum, which further strengthens the family and helps educate them in a patriotic spirit.

“Young artists from various cities and regions of Ukraine have been displaying their works in the exhibition hall for about 10 years. We are trying to follow up the efforts of Pavlo Tychyna, who used to support young people. The problems with the premises, which the museum faced 18 months ago, have been solved now. The museum continues to receive visitors.

“It is only sad that a negative and unattractive stereotype has been created around the figure of Tychyna, which a certain group of people actively support. Those who joined the Party much earlier (by age) than Tychyna and enjoyed all the privileges of this membership have now forgotten this. They do not even know Tychyna’s life story, including the fact that he went there only because he was the People’s Commissar of Education at the time and was supposed to have some impact on the schools policy.

“The first collection of poems, Clarinets of the Sun, won rave reviews. The first poetic attempts proved to be successful and were highly praised. But very soon Tychyna’s poetry came under scathing criticism, and there appeared a lot of those who were envious and tried to put things under the skids. Tychyna was rather a delicate and peaceful person who always shunned all forms of fighting and elbowing. He was an individual who stands aloof, looking up into the sky. He is conceiving a poem, happy or sorrowful, in his head at this moment. All depends on how painfully he was bitten. He did not know how to talk back.

“Now that we know history one can learn to read Tychyna between the lines and see what ideas he put into one poem or another. There is a subtext in each of his words — you just must know how to feel this. It is not for everybody, as you should not only relish the beauty of the word but also go deep into the content, where he manages, in short sentences, to express what makes his heart burn.

“Our goal is to teach the reader to see not only the esthetics but also the philosophy of poetry. In the 1920s and 1930s many of Tychyna’s poems were printed only once, never to be published again. But at that very time Tychyna composed the lines that characterize him as one who is taking a Ukrainian civic position.

“Among the commemorative events is the launch of an audio book of Tychyna’s Power and Tenderness of Pain (lyrical poems about Ukraine) recorded by Oleksandr Bystrushkin. Our museum hosted a discussion about this literary discovery. It lasts 40 minutes, like a school lesson. ‘Teachers may also use this disc, so it should be flawless,’ Bystrushkin said. The poems are set to the music composed by Borys Liatoshynsky, a friend of the poet. Besides, in February the National Philharmonic is going to host a soiree dedicated to the outstanding master.”