I associate the personality of Serhii YAKUTOVYCH with many things, such as a lay monk. Maybe, hence the link with the inner and outer image of Prince Dolgoruky. (Do you remember the 1769 portrait by master Samuil exhibited at Kyiv’s National Art Museum?) On the other end of my association range emerges Melancholy by the Polish modernist Jacek Malczewski: the artist stands lost in thought before an easeled canvass from which 3D human figures seem to be rushing into the studio’s space.

Yakutovych’s works impress me above all by being able to make me ponder the past and the eternal. They astonish me with their incredible energy, plasticity, panoramic display, and, at the same time, the artist’s extremely meticulous attention to detail. His pictures are a show of seething clashes, comparisons, overlapping and intertwining of characters, passions and textures. I also associate the figure of Yakutovych with such things as Chivalry, Honor, and Cossack Regalia, as well as, in his own words, Tenderness, Nobility, and Dignity. The artist once said: “I am lending an ear to my fate.” These words are extremely important for understanding this person.

“EVEN SHAKESPEARE WILL DO!”

There is a toy – a gray and slightly disheveled teddy bear – on the artist’s studio table. Yakutovych explains with a grin: “This is a birthday gift. I was told it is not just a toy but a creature in need of love and care. I racked my brains over the nickname and called it Gogol. (He shows the words written with a black felt-tip pen on the toy’s sole.) I don’t think Nikolai Gogol would take offense. He would laugh together with me.”

How do your works influence you? It is common knowledge that there is a feedback between the artist and his oeuvre.

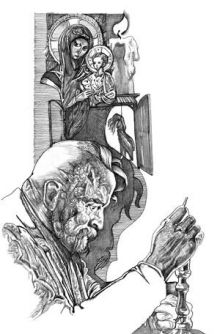

“I will say frankly: I almost never look back at my works. I’ve done something, spent some energy – and off we go. In general, I do not like my works very much. Some may think I camp it up when I say so. As for being influenced by what I draw… You must get absorbed as much as possible in what you are going to depict. If it comes to portraying a writer, for example, Gogol, I must reincarnate myself and become Gogol. I must feel all this from inside. I have just been working on illustrations to Lina Kostenko’s works, so I had to reincarnate in the poetess. She writes about Khmelnytsky in the poem Berestechko, so she must have reincarnated in him, too. And I… it is some kind of a double metamorphosis… But for this, I will be unable to create and will achieve nothing.

“I was once asked: ‘And when you take up Shakespeare, who would you like to be, which character?’ I said: ‘Shakespeare.’ The reply was: ‘What cheek!’ I can see why it should be so: a writer creates the world by means of words, and I by means of images. It is important for me not to illustrate the writer but to express him by the means that only an artist can have. I saw my father working on a piece of art for decades on end and finally finding what fitted in with his inner vision and sensation. This is why his works are flawless. But now the attitude to art and the process of creation is very light-minded, whereas the attitude to one’s place in the artistic hierarchy is all too serious.”

Do you mean the lust for glory, awards and prizes? For some reason, nobody wants posthumous recognition. Do you, a perfectionist, strive to achieve flawlessness in everything?

“I know that a work can sometimes scare the spectator with its flawlessness. This may sound odd. But in this case no spark-like contact emerges between the work and the one who perceives it. The spectator has doubts, knowledge, and a vision of his own, while the artist’s goal is not to stun him but to prompt him to think, worry, or, after all, read books. Sadly enough, people read very little now. Do you know which of the responses to the Gogol exhibits I liked the most? ‘Let’s hurry up home to reread Gogol,’ visitors once said to me. So I have achieved my goal. This is my victory. Last year we marked Gogol’s anniversary and argued over whether he was a Ukrainian or a Russian writer. But did many people read his oeuvres? That was a splendid occasion to do so! I have drawn many portraits of Gogol and really got the feel of him. His personality is a concentrated world that mixes good and evil. This is what you can find in the soul of every artist. A never-ending battle rages inside you. But for the struggle, things would look all too gray.”

We could talk of Gogol endlessly… Incidentally, as the production designer of the film Taras Bulba, you were awarded with the Golden Eagle. Is it double-headed?

“No, it is not double-headed but double-winged, as it should be. Working on Taras Bulba really exhausted me, but it was also an opportunity to implement many things in practice.”

(Yakutovych shows me a shooting sheet – an album of pencil-made drawings that reveal details, not only outlines, and convey the play of light and shade.)

It is just incredible to display such mastery in the composition and dynamics of scenes, shots, and details! Where did you get this knowledge? I would say you are reproducing reality – from a button to…”

“Yes, everything – from a button to the Sich in Khortytsia and Taras Bulba’s Cossack hamlet – was to be reproduced ‘as the real thing.’ Outfits, face types, landscapes, shooting angles, mise-en-scenes… It is my work. Sometimes I could not even guess why I suggested a certain item of, for example, Cossacks’ everyday life. Director Vladimir Bortko kept asking me if I really knew what the Cossacks washed with when there was no water at hand. I tried to persuade him it was kaolin, china clay. It cleans the skin splendidly. But I cannot recall where I learned this from. I also thought up of some details for the storyboards. But it is not empty fantasy – I just mustered all my previous experience, all that I had read before. I’ve read very much since my early childhood. All this accumulated and left imprints.”

“I AM JUST AN EPISODE IN A GRANDIOUSE PROJECT OF SEVERAL FAMILY TREES”

There were a lot of symbolic and prophetic episodes in your lifetime, especially in your childhood. Take the heartbreaking sensation of belonging to your soil, which you, still a boy, felt after viewing Dovzhenko’s Earth. Or take the moment that shaped you as an artist, when you, also still a little boy, ran a fever after watching the film Don Quixote, and your father said: “Why do you torment yourself so much? Just draw it.” Or the making of Shadows of the Forgotten Ancestors… All these things encrypted a lot of what materialized later: the life of a visionary artist, association with the cinema… You said once that you would like to make at least a paper replica of your ancestral home on Andriivsky Uzviz and populate it. Who would you populate it with?

“It would house all those who belong, one way or another, to my family tree: Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians; the Yakutovyches. Senchylos, and Kotovs. The residents would also include Shevchenko, both young and old; Mazepa by all means; Bulgakov; and Hrushevsky, for whom my great-grandmother worked as secretary; and very many others. It is an epic job to describe our family tree because the figures are unconventional, distinctive, and even outstanding. Among them are doctors, military men, architects, artists. So I have a feeling of tremendous responsibility for and belonging to them all. I am just an episode in a grandiose project of several family trees.”

When I hear you say this, I think it is an elementary thing for a normal individual. The feeling of responsibility and belonging… But many of us lack this very thing. These feelings can be alien even to the most intellectual people. You said somewhere that working with the Bortko team was like being at war: you always felt a rejection of your Ukrainian attitudes, your true patriotism.

“Oh, Bortko always taunted me: ‘You, nationalist!’ ‘Bandera…’ Indeed, it was very difficult to deal with the film crew from this viewpoint. On the one hand, they seemed to be testing me more than once as a professional and, finally, I dare say they began to respect me. On the other hand, they seemed unable to believe that I, one who studied in Moscow and in fact come from a Russian-speaking family, am such a ‘Mazepa lover.’ But I felt I had a supertask: to make them all, the entire film crew, love Ukraine. They, ethnic Russians and Jews with their imperial and other ambitions, saw the unique Ukrainian beauty, wonderful landscapes, Kyiv, Khotyn, Kamianets-Podilsky, Zaporizhia with Khortytsia, and affable people. They saw a Ukraine other than the one they visualized over there in Petersburg. I always tried to persuade them that the Zaporizhian Cossacks were in fact a knightly order, which puts us closer to Europe. At first they took an all too ironic approach to this. Then, when I told them all that I knew about the Cossacks, when they heard me describing that world, they concluded there was no point in arguing with me. They left this country in a happier and upbeat mood. Incidentally, the team was paid such a large per diem – for they worked outside Russia – that they all really pigged out and cut loose here.”

You mentioned knights. In any case, it is about dignity, probity, and chivalry. But our society seems to be oblivious to these personal traits. Moreover, the masses interpret them as ludicrous quixotism. But you once said there can be no national intelligentsia without this quixotism. In other words, society is degrading and degenerating. There are many temptations lying in wait for you. Have you ever caught yourself being haughty or envying somebody? How do you fight this?

“Naturally, I can also be arrogant and haughty. But I learned a thing or two from my parents. In general, my parents were very conscientious people. Sometimes they even seemed to go overboard. A role model is a powerful force. I learned from my father to keep my word. My family has never seen me drunk. I have been with and faithful to my wife for 38 years. And the feeling of dignity is not just empty words.”

Have you ever caught yourself hating and wishing to smash the offender?

“Naturally, I’ve been hurt more than once in my lifetime. But I am just indifferent to those who hate, envy or wish me evil. These people just cease to exist for me. No, I don’t know how to hate.”

You position yourself as a baroque person. Your Mazepa, Gogol, and Cossacks are baroque, one way or another, – not only in the visual dimension. But researchers describe a “baroque person” as one full of dramatic clashes between “earthly” and “celestial” essences and such incompatible feelings as lust for wealth and piety, an aspiration for righteousness and sinfulness...

“In my view, a baroque person is a person who has felt he is God and soared aloft. He has flown aloft and fell down like Icarus. This is what interests me the most: What does a person feel at the moment of existential doom and of futile exploit? In other words, quixotism. This is how I see and feel life. I still don’t think that the work, of which I love the very process and where ideas gush out, is in vain. Awards? Prizes? It is good if they come. But it is not essential. On the contrary, awards lull you and throw you back. So one should not hanker after them too much, one should be self-critical and move on.”

What do you mean by moving on – going even more into film-making?

“It may be so. Cinema is my old dream. I really worked on eight movies – two blockbusters and six documentary science films. And I entered the USSR Film Institute at first… But cinema has a terrible superhuman tension, when you are brutalized by, above all, a heavy-handed director, partners, and actors. It is untold suffering: almost all that I drew, say, for A Prayer for Hetman Mazepa – dozens of square meters – was destroyed. Out of the 98 figures made, only 17 have survived. But I know that I did it! I had to overcome myself. Still I was rushed to an emergency hospital after what I had gone through. Yet cinema attracts me. Even if there is no synopsis yet, I can ‘make a film’ and draw up storyboards. I will specify the details on my own. I can see them. I must see everything! I hope to collaborate with Oleh Kokhan – he is the only one in Ukraine to dare to produce films. Maybe, the future film will be directed by Zanussi – isn’t it great?”

But you are not going to drop book graphics, are you? You have illustrated over 160 publications, including 17 volumes of modern Ukrainian literature. What have you been working on of late?

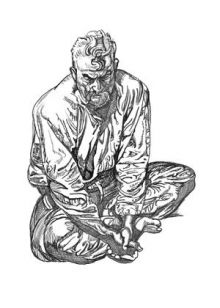

“I still remember my work on Lina Kostenko’s poem Berestechko. It was not an easy ride – 150 illustrations in six months. It seemed to be a well-known epoch, well-known figures and details. It is a poem not just about Khmelnytsky but about a man who lost everything. I was to find an adequate form, a free and transparent sketch, and it is not as simple as it may seem.”

“About a man who lost everything…” A terrible thing once happened to you: working in Spain, you lost grandiose, in terms of size and concept, canvases which are now “surfacing” throughout the world and cost fantastic money.”

“Yes, that was a very hard period in my life. Everything was lost. I used to wake up in tears for three years. But I had to muster the strength to live on – new motivations and stimuli for creative work. I am so maladjusted to everyday life. Sometimes this really gets my goat. Once my apartment lock broke down and I failed to fix it – the apartment remained unlocked for quite a time. I thought: Who will be interested in an unlocked house?

“I miss my wife Olha: she protected me and took up so many things. There is Olha’s corner in my studio, her portraits… I recently came across some of her works down here, of which I had never had an idea. I think I am again discovering Olha as an artist, although I knew how she worked and what she was capable of. I will say even this: she painted like Renoir. It is not without reason that Japan published her books in large numbers and they sold out almost immediately. For instance, the Ukrainian fairy tale A Crooked Little Duck sold out there in a month, bringing the publishers a handsome profit. Japan has also published books based on her fairy tales.”

My eye has caught an old etching printed in your album Unfinished Project, where you depicted your wife and yourself. It is written “Stop” just under her. I also remember a photo of Olha and you against the backdrop of a dark window. She looks into the eyepiece and you a bit sideways, and your facial expression suggests that you may have spotted a danger.”

“I so often catch myself thinking that I am an absolutely happy man, but God forbid anyone should suffer the losses that I did. But, on the other hand, life teaches you to be ready to face anything. Take horoscopes, for example. I was born under the sign of Scorpio and I used to bite myself quite a lot, especially in my youth. And, according to the Oriental calendar, I was born in a year of the Dragon. In China they burn a paper dragon-like kite after the celebrations, for the dragon must revive.”