A program called The Last Romantic: Return to Ukraine was presented in Chernihiv on May 15 and at the National Philharmonic Society in Kyiv the next day. Chernihiv "Philharmonia" Symphony Orchestra performed Ukrainian composer Serhiy Bortkevych’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in B Flat Major (op. 16) and Symphony No. 1 in D Major (Aus Meiner Heimat).

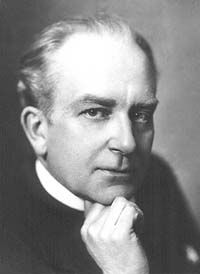

Serhiy Bortkevych was born in Kharkiv on February 28, 1877 and died in Vienna on October 25, 1952. His name and works are practically unknown in Ukraine where his first piano concerto premiered last May as part of a creative project sired by Meritorious Artiste of Ukraine Mykola Suk, who currently resides in the United States. In October 2000, the third part of the piano concerto was performed by Chernihiv’s Philharmonic.

This time Mykola Suk, who has revived a number of composers and their works in Ukraine, acted as an artistic consultant of the Last Romantic program. He had also obtained the unpublished original score of the first symphony. To this end, another name must be mentioned, a man that has spent more than thirty years studying Bortkevych’s creative legacy: Bhagwan Nebrhaj Thadani, resident of Winnipeg, Canada.

“Actually, we borrowed the program title from Mr. Thadani who has collected practically all of Bortkevych’s compositions,” says Mykola Sukach, Chernihiv "Philharmonia" Symphony Orchestra artistic director and conductor. “Now, owing to his enthusiasm and the research of Mykola Suk, we will have the bulk of the composer’s orchestral works (three piano and a number of violin and cello concertos).

“Of the three piano concertos, only the first one has a score, the other two are in clavier form, and we don’t know if the scores are available at all. If we don’t find them, I will do the instrumentation myself, keeping it in Bortkevych’s style. It will take several years, but my objective is playing whatever we can get, and in full, so the composer’s name returns to Ukraine.”

Indeed, why not include one of Bortkevych’s compositions in the Horowitz contest’s compulsory program? Then all Ukrainian musicians would automatically start performing it.

Also, Mykola Sukach dreams of a Serhiy Bortkevych Festival: “I can tell you from my own experience. A conductor has a special relationship with every composer. Some make you dissolve in their music, others demand more of the conductor’s willpower and his own vision of the music... And then for the first time I felt a composer’s actual presence. I don’t know how, I just felt it. An image made not only of sound. There was also a touch of philosophy and a host of other things that are hard to explain. It was not the sound of the Commander’s footsteps [an allusion to the opera Don Juan ], it was something I could sense and the awareness was strong.”

Mykola Sukach is convinced that the Finale of Bortkevych’s Symphony No. 1 is the best possible choice for the gala concert commemorating the tenth anniversary of Ukrainian independence, because it is festive Ukrainian music with a professional Russian symphonic touch.

He wonders why Bortkevych has been forgotten. He lived in Germany for fourteen years and then left. That was just an episode in his life. Then came thirty years in Austria. He lived and worked there, composing and giving concerts. His Austrian Suite was the only tribute to the new country of residence. The rest was music having nothing to do with Austrian national priorities. Considering that Austria begot Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, to mention but a few, they simply had no need for Bortkevych. In 1997, even his grave was destroyed by a bulldozer (Mr. Thadani told me).

Most importantly, Bortkevych’s name should be revived because his ethnic roots are in Ukraine. We are a cultured and talented nation. Even though Ukrainian music is quite cosmopolitan, Bortkevych’s rebirth will simply make our life richer. We all know that there is a sort of vacuum in Ukrainian classical music. Well, perhaps not a vacuum but the fact that we do not have that many brilliant composers, fewer by far than Russia.

Bortkevych wrote his first symphony in Vienna. An audio cassette of its rendition by the symphony orchestra of Vienna’s Philharmonic Society in 1948, conducted by the author, appeared in Chernihiv, also courtesy of Bhagwan Thadani. It is a remarkably tender melody against the powerful background of orchestration. The second and fourth parts are manifestly Ukrainian, with the second part expanding the Ukrainian theme, making it more Slavic, so much so that one yearns to hear balalaikas and gusli psalteries. The “visual” range of the fourth part lacks only a Ukrainian dance group and the theme is such one wants to hum it afterward.

Bortkevych’s piano concerto, written in 1910 and published in 1913, has themes easily associated with paganism. One is aware of the author, a modern intellectual, being given to the bylina Old Rus’ ballad, his keen awareness of his Slavic roots. Also, both compositions have a sense of alarm: nothing tragic, simply concern about the future. All his music is so drama-oriented, one is aware of the composer’s uplifted inspired visage not distorted by any grimaces.

“Some maintain that Bortkevych composed a la Rachmaninoff,” says Mykola Sukach. “Nothing of the kind. I am completely certain he wrote in his own way. It’s quite possible that he has the same meaning for Ukraine as Rachmaninoff has for Russia.”