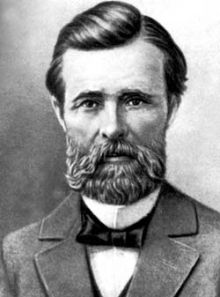

Every truly outstanding artist highlights certain turning points of his nation’s historical destiny not by “photocopying” reality, but by painting a general picture and the broadest possible panorama of an era. Ivan Semenovych Nechuy-Levytsky (1838-1918; real name: Ivan Levytsky), a classic of 19th-century Ukrainian literature, was no exception. This prominent writer produced brilliant novels and short stories that featured eloquent and full-blooded descriptions of almost every dimension of Ukrainian existence. He brilliantly depicted peasant life (Mykola Dzheria, Kaidash’s Family, The Factory Girl), the intelligentsia (Clouds), and the clergy (“The Vagabond of Athos,” Old-World Fathers and Mothers). The collected works of this writer, published in the 1960s, span 10 volumes, but not all of his works are represented here. But the point is not just quantity. The Ukrainian nation saw itself in Nechuy-Levytsky’s books as if in a magical artistic mirror. Ivan Franko rightly called Nechuy- Levytsky “the colossal all-embracing eye of Ukraine” and “a great visionary artist.”

Nechuy-Levytsky’s fictional works about contemporary life in 19th-century Ukraine have justly become part of the golden treasure of Ukrainian literature. In this article I will focus on that part of his literary legacy that deals with the history of Ukraine. These works are valuable from the viewpoint of general interest and education because the writer raises acute questions of national and state existence, such as the relationship between the authorities and the people, the “upper crust” and the “grassroots,” the essence of the Ukrainian national idea, loyalty to Ukraine, and betrayal, etc. Although most of these works, particularly the historical novel Prince Jeremi Wisniowiecki and the short story “Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky,” were written more than 100 years ago, certain lessons can still be drawn from them today.

How did the young Ivan Levytsky develop an interest in his national history? The future writer obtained his first “lessons of historical knowledge” in Cherkasy province from his father, who was a priest. In his twilight years, Nechuy reminisced, “When he and I would go to Korsun, he would point out Rizanyi Yar and the graves near Korsun, where Bohdan Khmelnytsky fought with the Poles; he would show us Nalyvaiko’s path that led from the Korsun road to the village of Petrushky.” Indeed, the land of Cherkasy seems to breathe history! The library of the elder Levytsky in the town of Stebliv contained the works of the well- known historians Dmytro Bantysh-Kamensky and Mykola Markevych, as well as the Cossack chronicles of Velychko, Samovydets and Hrabianka. Ukrainian folk dumas and historical songs also undoubtedly left their imprint on the gifted youth’s heart.

Later, when he was already traversing the thorny path of a Ukrainian man of letters, Nechuy- Levytsky made a concerted effort to write a series of popular brochures recounting the brightest pages of Ukrainian history for the “common” and “uneducated” reader (The Tatars and Lithuanians in Ukraine, The First Princes of Kyiv, Ukrainian Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky and the Cossacks, The Ukrainian Hetmans Ivan Vyhovsky and Yuriy Khmelnytsky, etc.) In the 1870s the popular Lviv-based newspaper Pravda praised the artistic and scholarly level of these works: “ This is a good piece of advice on how to write historical booklets for the common people without resorting to boring descriptions of the Riuryk princes’ genealogy or all kinds of Cossack battles and adventures.”

Yet, all these publications, including such works as the four-act operetta Marusia Bohuslavka (1875), the romantic fairy tale “Zaporozhians” (1875), and the play In Smoke and Flame, was a kind of prologue to the writer’s main historical prose works: the novel Prince Jeremi Wisniowiecki (written in 1896-1897 but first published in Kharkiv only in 1932) and the almost equally long novella “Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky” (published in Lviv in 1899, it finally appeared in Soviet Ukraine in 1991, the delay by no means caused by considerations of artistic quality).

Nechuy-Levytsky began to write his best prose works on Ukraine’s past after he was “well-armed” with life experience and historical knowledge. Ivan Franko correctly noted, “It is important for him to be able to look deep into the heart of society and describe it.” In his historical works the prominent Ukrainian writer studied the essential, primarily ethical, foundations of Ukrainian national life and tried to show how moral degradation and the disintegration of a personality reflect on the historical destiny of a nation in general and individuals in particular.

Both in the novel about Prince Wisniowiecki (Vyshnevetsky) and the short story about Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky, the author presents deep historically-motivated contradictions between moral duty, which every highly-developed personality should feel, and the actual (above all, social) condition of an individual. Prince Wisniowiecki (1612-1651) the grandson of the legendary founder of the Zaporozhian Sich, Dmytro “Baida” Vyshnevetsky, was the richest magnate in the Polish Rzeczpospolita, a talented general, an extremely ambitious and cruel ruler, who became a fierce butcher of his own people, reaping well-deserved hatred and earning the terrible nickname “Slavic Nero.” Thus, if an artist focuses on a truly extraordinary figure, like Wisniowiecki, the field for artistic, historical, and philosophical research is indeed broad.

We mostly see Wisniowiecki in those moments when he must make a decisive political, spiritual, and personal choice. Therefore, the most important thing for both the author and the reader is the motivating force of this individual’s choice and actions. The prince is an extremely vivid illustration of the fate of those “converts to Roman Catholicism,” the descendants of famous 13th-17th century Ukrainian clans, which, as Nechuy-Levytsky indignantly but justly noted, “only care about their own fortune, the pleasures and luxuries of life, and know nothing but the culture of the luxurious and splendid life of a wealthy landlord.” Wisniowiecki’s warped philosophy inevitably resulted in a terrible chasm between him and his former compatriots who, in his view, had become serfs and must be “civilized” by sword and fire and forcibly joined to the “proper Christian” culture. It is no accident that the first redaction of this novel bore the brief and witty sub-title “A Turncoat.” Ambition, thirst for power, and not least of all, myopia stemming from membership in a certain estate turned Wisniowiecki into Ukraine’s most implacable enemy, who betrayed the memory of his glorious grandfather. Although a large number of Polish historians still consider Wisniowiecki practically the embodiment of ideal chivalrous virtues, Nechuy-Levytsky showed a very different historical truth.

The writer uses Wisniowiecki’s life and early death as a background for discussing the values of high society (amply represented by the protagonist) and the lower classes. The prince himself exposes these “values” by which he is guided in the following words: “Ukraine with the hetmanate and the Cossacks are not to my liking. I will take a mace of my own and will not relinquish it to anyone. My hetman’s mace represents endless lands, untold sums of money, and an army. This is my force! With this I will win glory and perhaps the crown.” Thirst for power and patriotism are absolutely incompatible. Wisniowiecki deliberately chooses to serve the Polish state, although he is a Ukrainian, because he dreams, not unjustifiably, of the royal crown, even though he is well aware that the Polish Kingdom is “paradise for the nobility and hell for the peasants.” Ultimately, this historical figure left not fond memories of himself to posterity but hatred.

Even more useful and conducive to a clear understanding of the “genetic illnesses” of Ukrainian statehood, which have been tragically manifested for centuries on end is Nechuy-Levytsky’s short story “Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky.” The hero, Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s successor and his closest comrade-in-arms for many years, was one of the most dramatic figures in the history of 17th-century Ukraine — a talented and highly- educated individual, and a shrewd diplomat and politician, who sincerely wished Ukraine well. But Vyhovsky was also part and parcel of the Cossack officers’ estate, the estate that usually put its own narrow class interests above the prosperity of the entire nation. The novella shows this very convincingly. Is this not an object lesson for us today?

Naturally, the masses (uneducated and inclined to believe in the social demagogy of such “leaders” as Martyn Pushkar) do not accept this policy: they favor “equality” and, at the same time (a very interesting logical link), an alliance with Moscow, with the “white tsar” Aleksei Mikhailovich. Could this be the reason why Vyhovsky’s genuinely promising plan — the 1658 Treaty of Hadiach — ended in an utter fiasco? For although it is possible to sincerely consider the people a “conventional variable” in politics and act on this basis, it is absolutely impossible to win a more or less lasting victory without public support. The fact that the “rake that Vyhovsky stepped on” has not rusted in the past 350 years underscores the value of Nechuy-Levytsky’s novella: over and over again our leaders keep stepping on it.

Unable to understand their own people, turncoats like Wisniowiecki and, much to our regret, aristocratic hetmans of the Vyhovsky type inevitably sink into historical limbo. According to Nechuy-Levytsky’s assessment of the fruits of their rule, they were in fact “blind shepherds whom Ukraine refused to follow; Ukraine repudiated them, their descendants, and their seed as its enemies.” Finally, these two works are by no means “pulp fiction:” they impose a heavy burden on the nationally conscious Ukrainian, all the more so as these historical errors and political blindness are very reminiscent of current events. But this is precisely the goal of outstanding works of literature.