I sympathize with the honorable members of the Shevchenko Prize committee. They will have a hard time choosing the best of three gems. Three plays staged by drama theaters have been nominated for the main Ukrainian State Prize. Also nominated are two operas, but I will discuss only the plays. They are indeed remarkable — landmark — works. Their artistic level is so superior that it comes close to perfection.

Reaching a final decision is going to be painful. The committee will have to adopt additional important criteria for evaluating these works.

Kyiv — Dnipropetrovsk — Rivne is the geographical distribution of the nominees. The three plays originated in various types of theaters: one in a regional theater, another in a one-man municipal theater, and the third in a private theatrical enterprise. All three have been nurtured in the hearts of producers and actors who are concerned about Ukraine’s present and future, and Ukrainian culture and spiritual values. Let’s take a closer look at these theatrical gems.

GEM ONE, KYIV

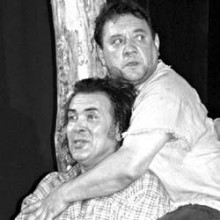

Based on the novel by the 20th-century American classic John Steinbeck, the play Of Mice and Men was staged by Vitalii Malakhov in the Beniuk-Khostikoiev Theater Company. It is a moving and tragic story of two friends. One of them is a mentally ill husky fellow with the soul of a child (played by Anatolii Khostikoiev). The other (played by Bohdan Beniuk) takes care of him and eventually kills him to spare him a violent death at the hands of an enraged mob. The big man loves mice, rabbits, and people so dearly and passionately that, oblivious of his strength, he inadvertently squeezes them to death with his big hands. His friend shoots him in the back of the head out of great love for this big child and in order to spare him the torment of an unavoidable lynching. He wants to help his totally vulnerable, naive, and mentally ill friend to pass over death’s threshold and move on to the longed-for and tender better world. That is, love in all its manifestations ends in death. Love is equal to death.

Malakhov’s play features a constellation of brilliant actors from the Ivan Franko Theater that we have missed so much in some other plays staged by Ukraine’s leading theater. The characters played by Volodymyr Nechyporenko, Nataliia Sumska, and others come across as ambivalent, or even philosophical, figures. The great ethical achievement of the play is that its creators have found a place in the plot for their extremely ill fellow actor Volodymyr Abozopulo — they introduced a fitting part of a man with a maimed throat and an artificially produced voice.

The play was first staged some time ago, in 2005, but it is still popular with theater audiences. Its value for Ukrainian culture lies in the fact that it transcends provincialism and introduces the national theater to contemporary classics. Without evoking any associations with Ukrainian realities, the play deals with universal human values.

GEM TWO, DNIPROPETROVSK

Based on a story by Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Sin is staged by Mykhailo Melnyk, the sole creator, manager, artistic director, and leading actor of Kryk, once a private theater and now a municipal theatrical enterprise. This is a blood-curdling and heart-wrenching story of a Ukrainian wearied by life, whose old, exhausted mother cannot die and is vegetating in the house. She makes life miserable for everybody and asks her son to take her to a forest in winter and leave here there to die. His soul is torn apart as he searches for a tragic decision. Here too life is equal to death.

The play features Melnyk’s amazing performance of the dialogue between the son and his mother, who is unseen. The play is highly metaphorical and replete with visual and dynamic imagery. The music is stirring and tears involuntarily well up in your eyes, even though the actor eschews direct, soapy melodrama. The play offers the spectator general associations with Ukraine’s bitter lot and its miserable children with grief-stricken hearts.

GEM THREE, RIVNE

Berestechko is a theatrical translation of a poem written by the brilliant Lina Kostenko about Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s military defeat, spiritual devastation, and the restoration of his power. Producer Oleksandr Dzekun has imbued the play with rich imagery and symbols, Ukrainian rituals, and folk and church songs. The stage is strewn with black and white grain, planted with spears, and lit by candles. Water represents ablution and cleansing, while the red guilder-rose berries symbolize Khmelnytsky’s bleeding body and spirit. Aware of his destiny, fame, and infamy, and filled with prescient knowledge of future conflicts and Ukraine’s bitter cup, Khmelnytsky (played by Volodymyr Petriv) nonetheless sits at the potter’s wheel in the final scenes and in utter riveting silence, watched by the spellbound audience, makes a small pot — the Ukrainian state.

The play by the Rivne Regional Theater impregnates the word of a contemporary poet and prophet with emotional force, impassioned national energy, and profound philosophical meaning, all of which is conveyed not only by the sound of the stanzas but also by the carefully constructed mises en scene, scenic action, and visual symbolic signs. Theater is all about spectacular entertainment, and in the play by the Rivne-based theater this kind of entertainment is fascinating and thought-provoking.

Having lived through the heroic death of his fellow Cossacks (“... three hundred of our brothers died here...”), the ultimate betrayal by his allies and closest associates, absolute despair, and essentially a spiritual death, in Berestechko Khmelnytsky comes to life for love, song, clay, arms, woman, Fatherland, and future — through death for life and love.

As far as these three outstanding plays are concerned, in my opinion this evaluation criterion is decisive. Love that gravitates and leads to death in the first two plays is overwhelming but also terrifying. What we find in Berestechko is death vanquished by love and the life-giving hope that we will, after all, build our Ukraine. My vote goes to Berestechko.

The Shevchenko Prize committee will, of course, make its own decision. Nevertheless, I believe that the State Prize nomination is in itself a great reward to an artist because his “wearisome labor and mind’s high aspirations” have been singled out from among many others and found worthy. On the occasion of this achievement I would like to extend my heartfelt congratulations to those people who are so dear to my theater-loving soul — Vitalii Malakhov, Anatolii Khostikoiev, Bohdan Beniuk, Mykhailo Melnyk, Oleksandr Dzekun, and Volodymyr Petriv.