Kabuki, geisha, netsuke – what many Europeans consider symbols of Japan – emerged in the Edo era. This period, when Tokugawa shoguns ruled the country, lasted from the early 17th until the mid-19th century. A particular urban culture was formed in Edo, the capital of the ruling clan, at the time. The exhibit “Edokko Travels” at Kyiv’s National Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko Museum shows what cheered, angered, and inspired Edokkos, i.e., residents of Edo. This event is part of the Year of Japan in Ukraine. The exposition displays colored engravings, decorative and applied art works of the Edo period such as weapon elements, tableware, and netsuke sculptures.

A WITTY BON VIVANT

Fierce internecine wars raged in Japan in the late 16th century. In 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated a military coalition of princes in the Battle of Sekigahara, and the emperor soon granted him the title of grand shogun. It was the beginning of the Edo period.

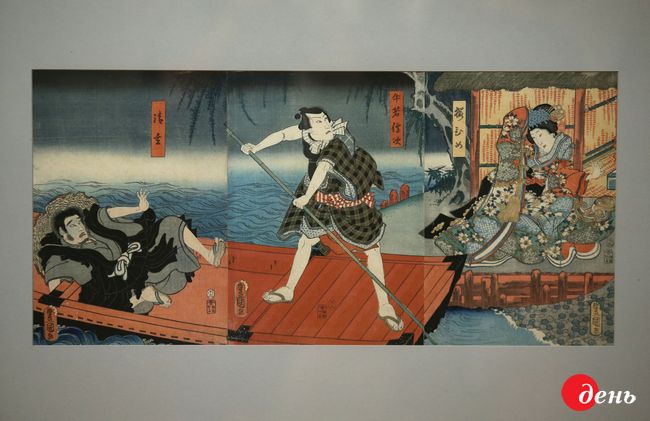

UTAGAWA KUNISADA, A SCENE FROM THE PLAY SEAGULLS AND WHITE WAVES

“Tokugawa shoguns saw to it that there was peace and the order they had established,” says Halyna Bilenko, the exhibit curator, head of the Khanenko Museum’s Oriental art section. “The first of them, Ieyasu, made Edo, a town near Tokyo Bay, his capital. Its name means ‘estuary’ in Japanese. Edo is rapidly developing. The Tokugawa clan demands that the princes loyal to them arrive in Edo and stay there for a year. So princely estates are being built, the nobles are bringing over their menials and samurais, they need house owners and servants. People are filling Edo. The city is growing fast, and its population reaches a million in the early 18th century. This forms what is known as ‘Edo child,’ i.e., Edokko.”

In general, the Edokko is a witty bon vivant who is not afraid to take risk, loves the kabuki theater and beauties, and is well-mannered. “He may be a servant, but he is conceited and has his own idea of honor and elegance,” Bilenko adds.

CENSORSHIP IN ART AND FREEDOM IN LOVE

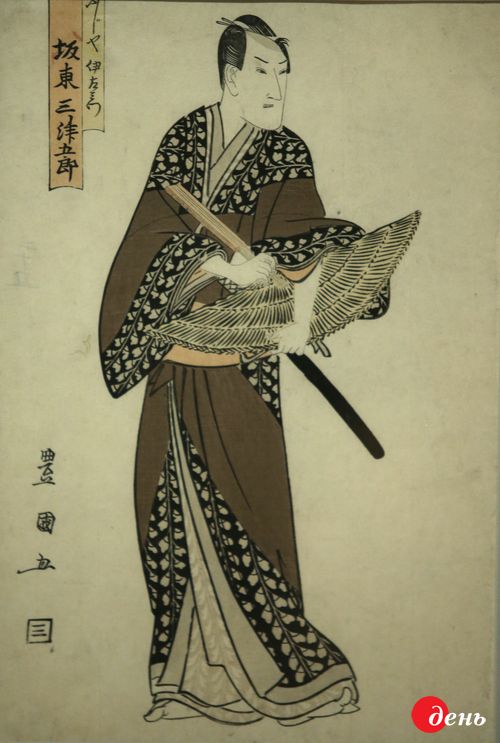

It is in the Edo period that the famous Japanese xylography – ukiyo-e engraving – emerged. Artists sang praises of urban life: they depicted geishas, landscapes, and kabuki actors in their star roles.

There was rigid censorship at the time. Incidentally, the well-known artist Kitagawa Utamaro, who painted beautiful women, suffered from this. “Utamaro and his publisher friend made a series of woodblock prints. The Tokugawa decided that the artist derided members of their families. Utamaro and his friend were arrested and then freed, but the artist took it very close to heart and died soon after,” Bilenko says.

Yet the Tokugawa showed leniency to some things. In the early 17th century, these rulers established licensed “red-light districts,” the first of which, Yoshiwara, was in Edo. But there was a ruse here: geishas in the “love district” were supposed to distract a large number of men from unnecessary rebellious thoughts. In Bilenko’s words, those districts formed the image of a refined object of men’s love. It is of no wonder because geishas, who often came from impoverished noble families, were well-versed in literature, music, and other arts. Naturally, they also inspired writers and artists.

500 KILOMETERS OF ADVENTURES

A large part of the exhibit is about 20 prints of the “53 stations of the Tokaido road” series created in the mid-19th century by Utagawa Kunisada. Tokaido is a road between Edo and Tokyo, the then imperial capital. It was an important economic artery with a host of small towns, shops, and sights to see. “A lot of illustrious events took place down the 500 kilometers of this road,” Bilenko says. Kunisada depicted kabuki actors in their hallmark images at the Tokaido stations.

Owing to the artist’s mastery and the subject itself – theater stars against the backdrop of well-known landscapes, – the series was fated to be popular. As Bilenko points out, it was then decided that Edo guests would be interested in having albums with these prints as a keepsake. So the “53 stations of the Tokaido Road” series was printed in a large number by various publishers.

IN RAPTURE OVER OLD JAPAN

The year 1868 saw the so-called Meiji Restoration. The country was now ruled directly by the emperor, not by a military shogunate. Japan began to carry out socioeconomic reforms and open up to the world. That was the end of the Edo era. But Edo did not decline: the imperial residency moved there, and now this city, known as Tokyo, is the capital of Japan.

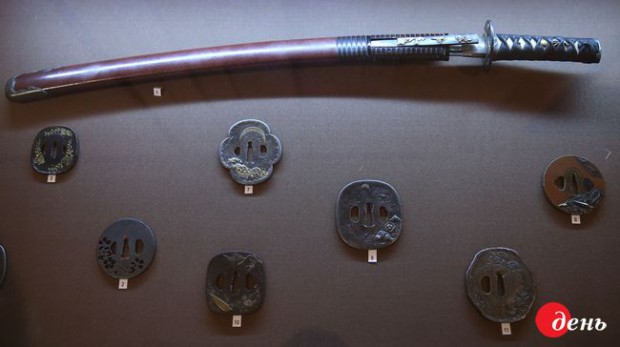

During the Meiji Restoration, the country began to develop at a rapid pace, and its culture enchanted Europe. Western artists used Japanese subjects, and museums and private collectors hunted for exotic things from there. Bohdan Khanenko, too, acquired 237 colored woodblock prints and a collection of 400 tsubas (samurai sword guards) in 1912 in Paris.

This collection in fact forms the bulk of the exhibit. The museum is showing a lot of artworks, including those of the “53 stations of the Tokaido road” series, for the first time. The exposition also includes a work by the contemporary calligrapher Morimoto Ryuseki. A big sheet bears the India-ink-drawn hieroglyphs that mean “Take a noble action, and the problem will be solved by itself.” Edokkos might have also been guided by this rule.

The “Edokko Travels” exhibit at the Khanenko Museum will remain open until September 3.